Stakeholder Engagement Process¶

A crucial component of AI Sustainability is conducting an appropriate Stakeholder Engagement Process (SEP). But before we delve into the process itself, we must ask, what is a stakeholder?

Key Concept: Stakeholder

Stakeholders are individuals or groups that:

(1) have interests or rights that may be affected by the past, present, and future decisions and activities of an organisation;

(2) may have the power or authority to influence the outcome of such decisions and activities;

(3) possess relevant characteristics that put them in positions of advantage or vulnerability with regard to those decisions and activities.

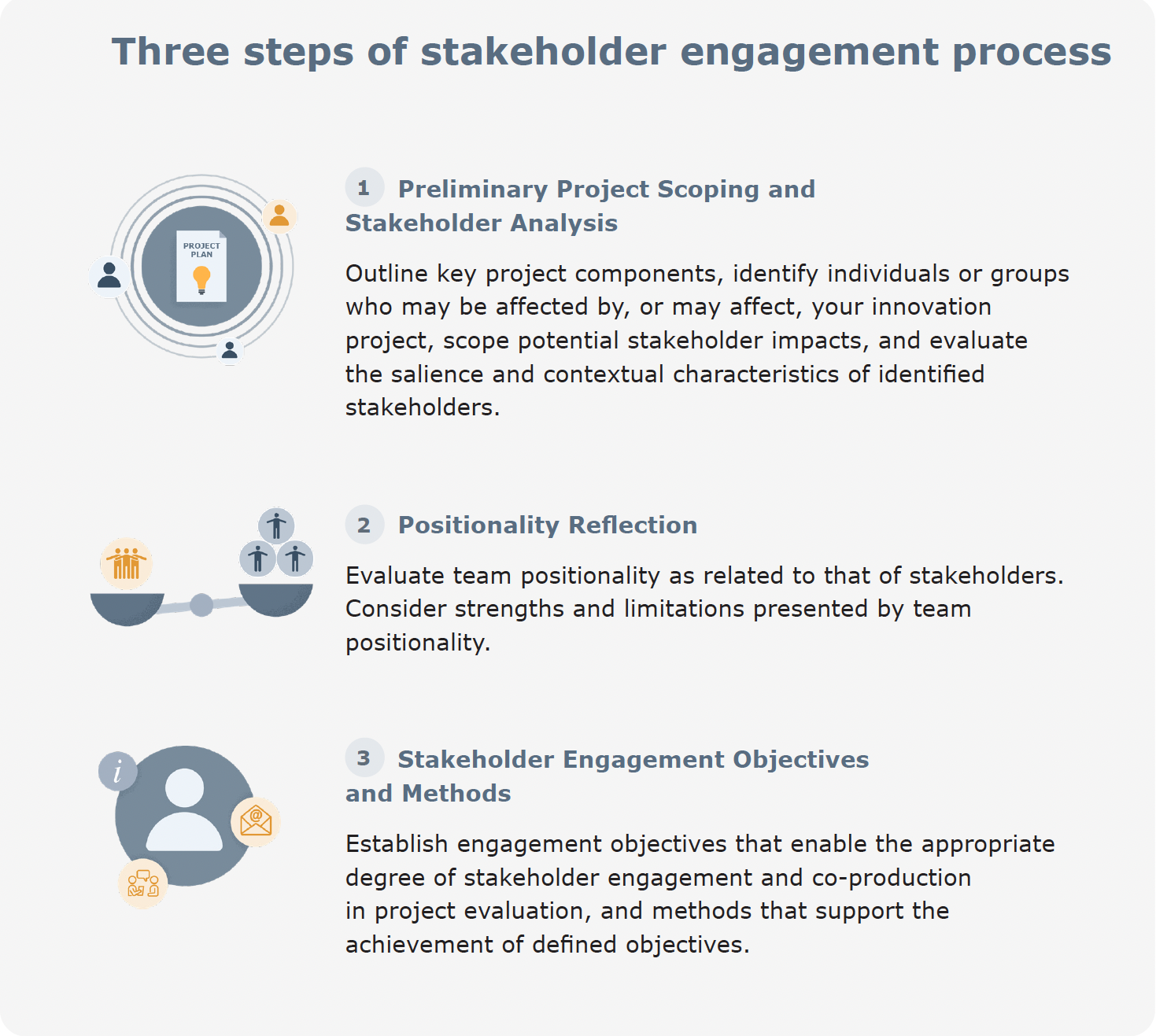

The SEP is an iterative process with three core steps:

Each of these activities should be documented and utilised to create a Project Summary (PS) report. A Project Summary Report is comprised of four components reflecting the SEP process: (1) a preliminary project scoping and stakeholder analysis, (2) a positionality reflection (3) an overview of established stakeholder objectives and methods and (4) a governance workflow map. The fourth component of the PS Report will be discussed later in the course when we look into accountability and governance of AI systems.

We will now analyse each of the relevant steps within the process and look at how they relate to thinking about the sustainability of the project as a whole.

Preliminary Project Scoping and Stakeholder Analysis¶

This is the first activity within the SEP process. It involves four sub-steps:

-

Outlining project use context, domain, and data: In this step, a high-level description of the prospective system is outlined. This includes the domain in which it will operate, the contexts in which it will be used, and the data on which it will be trained. During this initial project scoping activity, information should be drawn from organisational documents (i.e., the project business case, proof of concept, or project charter), project team collaboration, as well as desk research (if necessary) to complete the description.

-

Identifying stakeholders: Once the first step is completed and building on this contextual understanding, this step involves identifying who may be affected by, or may affect the project.

-

Scoping potential stakeholder impacts: This involves carrying out a preliminary evaluation of the potential impacts of the prospective AI system on affected individuals and communities. At this initial stage of reflection, members of the project team should review the SUM values, and the corresponding ethical concerns, rights and freedoms, and then consider which of these could be impacted by the design, development and deployment of the prospective AI system and how.

-

Analysing stakeholder salience: The step requires assessing the relevance of each identified stakeholder group to the AI project and to its use contexts. This includes assessing the relative interests, rights, vulnerabilities, and advantages of identified stakeholders as these interests, rights, vulnerabilities, and advantages may be impacted by, or may impact, the AI system in question. When identifying stakeholders, the project team should also consider organisational stakeholders, whose input will likewise strengthen the openness, inclusivity, and diversity of the project.

Stakeholder analyses may be carried out in a variety of ways that involve more-or-less stakeholder involvement. This spectrum of options ranges from analyses carried out exclusively by a project team without active community engagement to analyses built around the inclusion of community-led participation and co-design from the earliest stages of stakeholder identification. The degree of stakeholder involvement will vary from project to project based upon a preliminary assessment of the potential risks and hazards of the model or tool under consideration.

Low-stakes AI applications that are not safety-critical, do not directly impact the lives of people, and do not process potentially sensitive social and demographic data may need less proactive stakeholder engagement than high-stakes projects. For example, an application which sorts out email and identifies spam may be correctly classified as low impact and low risk.

A responsible and thorough initial evaluation of the scope of the possible risks that could arise from the AI system (to be carried by the team responsible for developing said system) will determine the the potential hazards the project poses to affected stakeholders (be them individuals or communities). A reasonable assessments of the dangers posed to individual wellbeing and public welfare is needed in order to formulate proportionate approaches to stakeholder involvement.

Regardless of the potential impacts of a project, involving affected individuals and communities in stakeholder analysis (and, later, in stakeholder impact assessment) should, in all cases, be a significant consideration. Stakeholder involvement ensures that a project will possess an appropriate degree of public accountability, transparency, legitimacy, and democratic governance, and it recognizes the important role played in this by the inclusion of the voices of all affected individuals and communities in decision-making processes.

In addition to providing these important supports for building public trust, stakeholder involvement can help to strengthen the objectivity, reflexivity, reasonableness, and robustness of the choices a project team makes across the project lifecycle. This is because the inclusion of a wider range of perspectives (especially of those who are most marginalised) can enlarge a project team’s purview, expand its domain knowledge as well as its understanding of citizens’ needs. It can likewise unearth potential biases that may arises from limiting the standpoints that inform decision-making to those of team members.

Public engagement and community involvement, however, are only one part of the measures a team needs to take to ensure the objectivity, reflexivity, reasonableness, and robustness of its stakeholder analysis, impact assessment, and decision-making, more generally. Apart from outward-facing community participation, processes inward-facing reflection should also inform the way the team approaches to these challenges (see the sustainability, engagement, and reflection cycle).

Positionality Reflection¶

All individual human beings come from unique places, experiences, and life contexts that have shaped their thinking and perspectives. Reflecting on these is important insofar as it can help team members understand how their viewpoints might differ from those around them and, more importantly, from those who have diverging cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds and life experiences.

Identifying and probing these differences can enable individuals to better understand how their own backgrounds, for better or worse, frame the way they see others, the way they approach and solve problems, and the way they carry out research and engage in innovation. By undertaking such efforts to recognise social position and differential privilege, they may gain a greater awareness of their own personal biases and unconscious assumptions. This then can enable them to better discern the origins of these biases and assumption and to confront and challenge them in turn.

Social scientists have long referred to this kind of self-locating reflection as “positionality”. When team members take their own positionalities into account making them explicit, they can better grasp how the influence of their respective social and cultural positions creates strengths and limitations.

On the one hand, one’s positionality—with respect to characteristics like ethnicity, race, age, gender, socioeconomic status, education and training levels, values, geographical background, etc.—can have a positive effect on an individual’s contributions to an innovation project; the uniqueness of each person’s lived experience and standpoint can play a constructive role in introducing insights and understandings that other team members do not have. On the other hand, one’s positionality can assume a harmful role when hidden biases and prejudices that derive from a person’s background, and from power imbalances and differential privileges, creep into decision-making processes undetected.

When taking positionality into account, team members should reflect on their own positionality matrix. They should ask: To what extent do my personal characteristics, group identifications, socioeconomic status, educational, training, & work background, team composition, & institutional frame represent sources of power and advantage or sources of marginalisation and disadvantage? How does this positionality influence my (and my team’s) ability to identify & understand affected stakeholders and the potential impacts of my project? Several other questions must be asked to respond to these two: How do I identify? How have I been educated and trained? What does my institutional context and team composition look like? What is my socioeconomic history?

Stakeholder Engagement Objective and Method¶

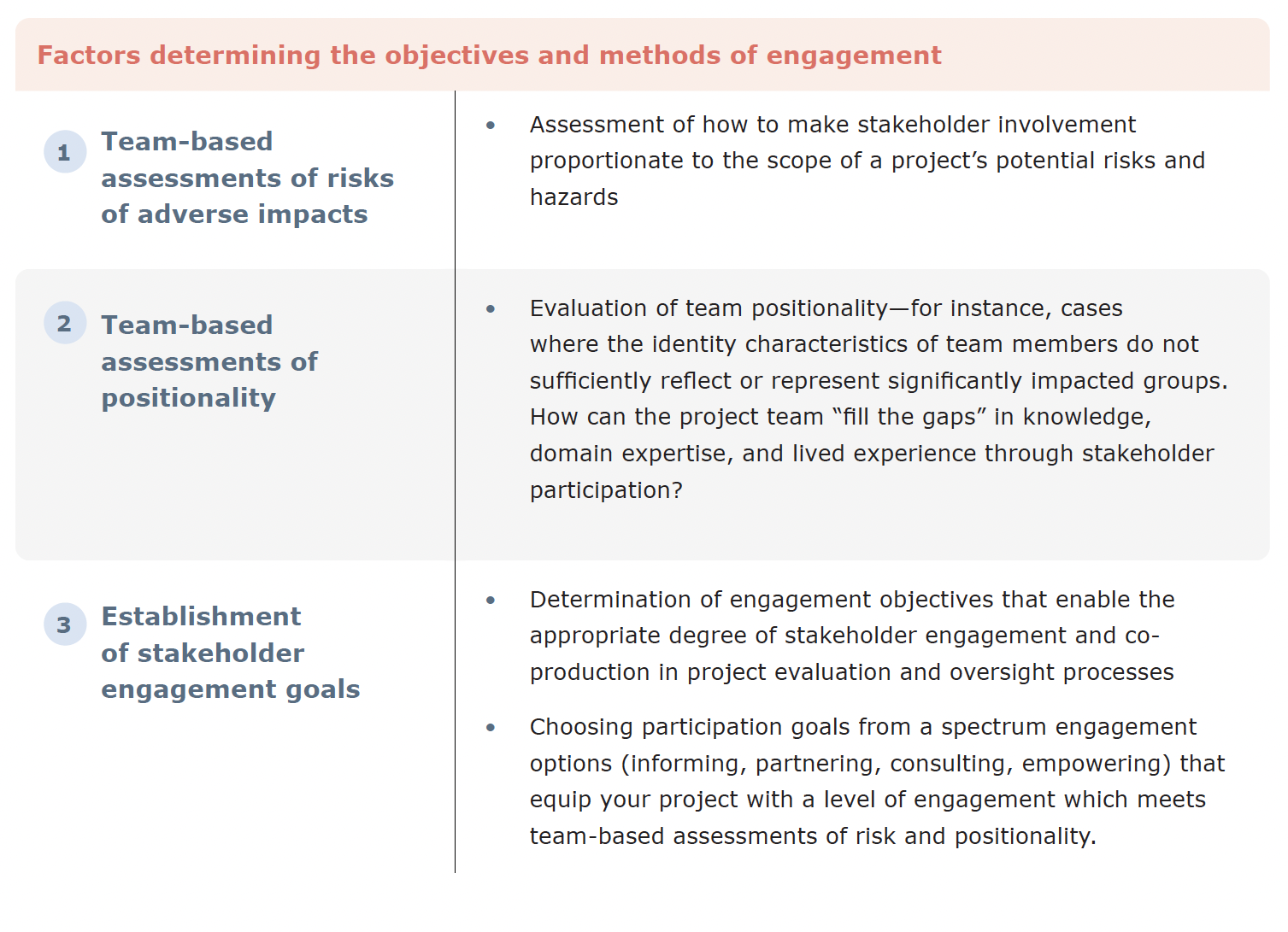

Once the initial project scoping, stakeholder analysis, and positionality reflection have been done, a project team can move on to define the objective for their stakeholder engagement, as well as the method(s) to be used.

As we have previously established, stakeholder engagement may be carried out in a variety of ways that involve more-or-less stakeholder involvement. This spectrum of options ranges from analyses carried out exclusively by a project team without active community engagement to analyses built around the inclusion of community-led participation and co-design from the earliest stages of stakeholder identification.

The degree of stakeholder involvement will vary from project to project and take into account a preliminary assessment of the potential risks and hazards of the model or tool under consideration. Low-stakes AI applications that are not safety-critical, do not directly impact the lives of people, and do not process potentially sensitive social and demographic data may need less proactive stakeholder engagement than high-stakes projects. Similarly, the project team will need to take into account their assessment of positionality.

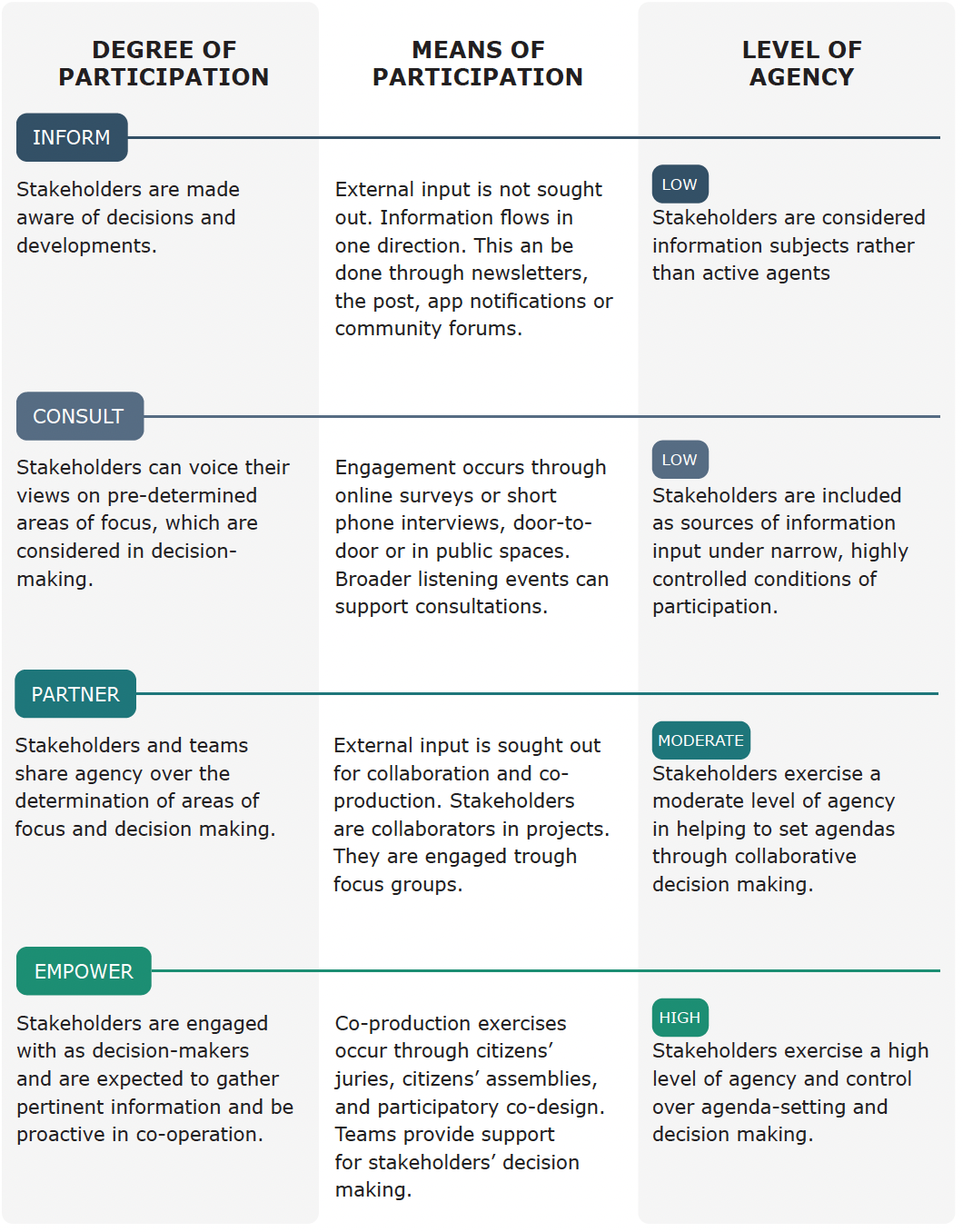

When weighing these three factors, the team should prioritise the establishment of a clear and explicit stakeholder engagement objective and document this. This is crucial, because all stakeholder engagement processes can run the risk either of being cosmetic tools employed to legitimate projects without substantial and meaningful participation or of being insufficiently participative, i.e. of being one-way information flows or nudging exercises that serve as public relations instruments. The purpose of stakeholder involvement in sustainable AI projects is just the opposite: to amplify the participatory agency of affected individuals and organisations in impact assessment, risk management, and assurance processes.

To avoid such hazards of superficiality, the team should shore up its proportionate approach to stakeholder engagement with deliberate and precise goal-setting. There are a range of engagement options that can help a project obtain a level of public participation which meets team-based assessments of impact and positionality as well as practical considerations and stakeholder needs.

Defining a Stakeholder Objective¶

Selecting a Stakeholder Engagement Method¶

The following table summarises a wide range of salient methods:

| Mode of Engagement | Description | Degree of Engagement | Practical Strengths | Practical Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newsletters (email) | Regular emails (e.g.: fortnightly or monthly) that contain updates, relevant news, and calls to action in an inviting format. | INFORM |

Can reach many people; can contain large amount of relevant information; can be made accessible and visually engaging. | Might not reach certain portions of the population; can be demanding to design and produce with some periodicity; easily forwarded to spam/junk folders without project team knowing (leading to overinflated readership stats). |

| Letters (post) | Regular letters (e.g.: monthly) that contain the latest updates, relevant news and calls to action. | INFORM |

Can reach parts of the population with no internet or digital access; can contain large amount of relevant information; can be made accessible and visually engaging. | Might not engage certain portions of the population; Slow delivery and interaction times hampers the effective flow of information and the organisation of further engagement. |

| App notifications | Projects can rely on the design of apps that are pitched to stakeholders who are notified on their phone with relevant updates. | INFORM |

Easy and cost-effective to distribute information to large numbers of people; Rapid information flows bolster the provision of relevant and timely news and updates. | More significant initial investment in developing an app; will not be available to people without smartphones. |

| Community fora | Events in which panels of experts share their knowledge on issues and then stakeholders can ask questions. | INFORM |

Can inform people with more relevant information by providing them with the opportunity to ask questions; brings community together in a shared space of public communication. | More time-consuming and resource intensive to organise; might attract smaller numbers of people and self-selecting groups rather than representative subsets of the population; effectiveness is constrained by forum capacity. |

| Online Surveys | Survey sent via email, embedded in a website, shared via social media, etc. | CONSULT |

Cost-effective; simple mass- distribution. | Risk of pre-emptive evaluative framework when designing questions; Does not reach those without internet connection or computer/smartphone access. |

| Phone Interviews | Structured or semi-structured interviews held over the phone. | CONSULT PARTNER |

Opportunity for stakeholders to voice concerns more openly. | Risk of pre-emptive evaluative framework when designing questions; Might exclude portions of the populations without phone access or with habits of infrequent phone use. |

| Door-to-door interviews | Structured or semi-structured interviews held in-person at people’s houses. | CONSULT PARTNER |

Opportunity for stakeholders to voice concerns more openly; can allow participants the opportunity to form connections through empathy and face-to- face communication. | Potential for limited interest to engage with interviewers; time-consuming; can be seen by interviewees as intrusive or burdensome. |

| :fontawesome-solid-people-arrows-left-right: In-person interviews | Short interviews conducted in- person in public spaces. | CONSULT PARTNER |

Can reach many people and a representative subset of the population if stakeholders are appropriately defined and sortition is used. | Less targeted; pertinent stakeholders must be identified by area; little time/interest to engage with interviewer; can be viewed by interviewees as time- consuming and burdensome. |

| Focus Groups | A group of stakeholders brought together and asked their opinions on a particular issue. Can be more or less formally structured. | CONSULT PARTNER |

Can gather in-depth information; Can lead to new insights and directions that were not anticipated by the project team. | Subject to hazards of group think or peer pressure; complex to facilitate; can be steered by dynamics of differential power among participants. |

| Online Workshops | Workshops using digital tools such as collaborative platforms. | CONSULT |

Opportunity to reach stakeholders across regions, increased accessibility depending on digital access. | Potential barriers to accessing tools required for participation, potential for disengagement. |

| Crowdsourcing (Online) | Well-designed tasks that can be undertaken by a distributed collective, with individuals working on separate components. | CONSULT PARTNER |

Opportunity to engage stakeholders across regions, in an asynchronous manner, with increased accessibility depending on digital access. Supports increased potential for diverse forms of expertise and experience. | Can be misused as a method for outsourcing cheap labour; potential barriers to accessing tools required for participation; potential for disengagement; difficult to ensure accuracy and validity of input from participants. |

| Distributed Project Collaboration (Online) | Online digital platforms, such as GitHub, enable new forms of citizen science and collaborative development on diverse projects (e.g., open source software, open science). | CONSULT PARTNER EMPOWER |

Opportunity to engage stakeholders across regions, in an asynchronous manner, with increased accessibility depending on digital access; increased potential for diverse forms of expertise and experience; empowers new communities to actively participate in shaping and building tools that have real value for their communities. | Potential barriers to accessing digital tools required for participation, including high levels of digital literacy. |

| Citizen panel or assembly | Large groups of people (dozens or even thousands) who are representative of a town/region. | INFORM CONSULT PARTNER EMPOWER |

Provides an opportunity for co-production of outputs; can produce insights and directions that were not anticipated by the project team; can provide an information base for conducting further outreach (surveys, interviews, focus groups, etc.); can be broadly representative; can bolster a community’s sense of democratic agency and solidarity. | Participant rolls must be continuously updated to ensure panels or assemblies remains representative of the population throughout their lifespan; resource-intensive for establishment and maintenance; subject to hazards of group think or peer pressure; complex to facilitate; can be steered by dynamics of differential power among participants. |

| Citizen jury | A small group of people (between 12 and 24), representative of the demographics of a given area, come together to deliberate on an issue (generally one clearly framed set of questions), over the period of 2 to 7 days (Involve.org.uk. | INFORM CONSULT PARTNER EMPOWER |

Can gather in-depth information; can produce insights and directions that were not anticipated by the project team; can bolster participants’ sense of democratic agency and solidarity. | Subject to hazards of group think; complex to facilitate; risk of pre-emptive evaluative framework; small sample of citizens involved risks low representativeness of wider range of public opinions and beliefs. |

As with all forms of engagement, deciding on the best method requires awareness of your audience. Consider the following cases:

A research team has released results from an economics study that could have a positive impact on public policy. They decide to share these results with policymakers. The goal is to directly influence policy. Therefore, the results need to be clearly communicated and also connected to the policy goal. This connection is important to help ensure that policy-makers are able to evaluate the wider implications of the scientific findings.

Communication Goal: to demonstrate how scientific findings can support evidence-based policy impact

As part of an education outreach campaign to improve digital literacy among adolescents, a mental health charity are running workshops with secondary school students. They wish to communicate recent evidence about the impact of over-using social media on mental health. Rather than communicating complicated statistical information about the methods used in their study, the team develop a more accessible form of their findings and link these findings to practical steps that the students can take to protect themselves online.

Communication Goal: to build awareness of possible risks associated with excessive social media usage and support behavioural change strategies

A PhD student working in a Physics department has results from a recent study that developed and tested a new method for the large-scale data mining of astronomical data. The PhD student wishes to present this new method and the validation study at an upcoming international conference for data science. The audience will be technically literate, but will not have specialist expertise in astronomy. Therefore, the PhD student describes the method in the context of its original study buy also emphasises the generalisability for other sciences (e.g. genomics).

Communication Goal: to advance academic career by gaining experience of presenting conference papers and also generating interest in a novel data science method.