Climbing the Ladder: From Informing to Empowering¶

In 1969, Sherry Arnstein published 'A Ladder of Citizen Participation' [@arnstein1969]. The eponymous ladder was a typology of different forms of public participation in science and research, which was intended to be both "provocative" and also facilitate clearer dialogue on the objectives of different forms of public engagement1.

Arnstein visualised her typology as a ladder to signify that the higher rungs represent increasing forms of "citizen power". In order from lowest to highest, the eight rungs are as follows:

Arnstein's Ladder of Public Participation

- Manipulation

- Therapy

- Informing

- Consultation

- Placation

- Partnership

- Delegated Power

- Citizen Control

With each step up the ladder, we move closer to a genuine form of public participation that seeks to empower citizens through distributed forms of knowledge production and enhanced capabilities. For instance, perhaps a local council sets out to engage and upskill residents to enable them to have greater control over how their data are used to improve local services.

Such a project could represent any of the top three rungs, depending on how the project was designed and organised. Like the other rungs, this is because the top three rungs form a separate category that further delineates them from the lower levels. The categories are as follows:

- Nonparticipation (Manipulation, Therapy)

- These rungs describe forms of participation that have been "contrived by some to substitute for genuine participation". However, the goal of these non-participatory forms of public engagement are often to enable those in power (e.g., researchers) to "educate" participants.

- Tokenism (Informing, Consultation, Placation)

- These rungs afford participants a voice but only insofar as their views serve the interests of those who hear them. Participants still lack any real sense of power in such forms of engagement, as researchers still make the final decision based on pre-determined goals or values.

- Citizen Power (Partnership, Delegated Power, Citizen Control)

- The higher rungs empower participants to an increasing degree. Where members of the public can enter in partnerships with researchers, they will likely be granted autonomy over decisions. However, the extent to which this power is truly delegated or under the control of the participants may be limited at this level. Each step up the ladder from here represents increased power and autonomy over decision-making.

Notice that even the lowest levels would, technically, constitute a form of engagement, while failing to count as genuine forms of participation.

In the approximately 50 years since this article's publication many have engaged with Arnstein's original proposal, including critical perspectives that emphasise the model's limitations. The ladder is, after all, a simplification—like all heuristic models. As such, it fails to capture variations across policy or research domains, such as education versus healthcare, where participants may not wish or be able to exercise power or autonomy over decisions but could benefit from other forms of empowerment. In addition, the model is unable to provide insights into what can be done to rebalance, rather than outsource, power in specific contexts.

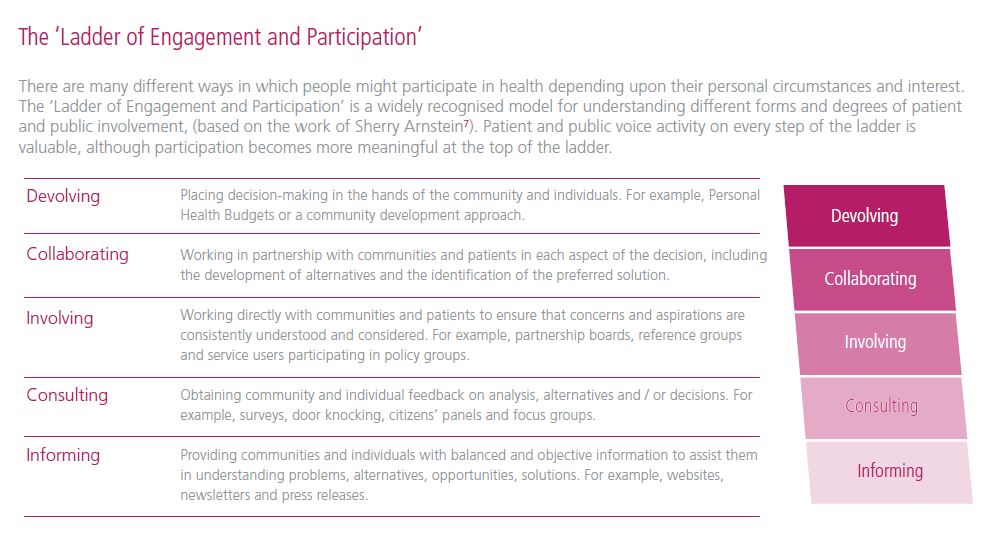

Nevertheless, in spite of these limitations, the model that Arnstein developed has been highly influential. For instance, NHS England have a simplified form of Arnstein's ladder, which is better suited to help structure patient and public involvement or activities (e.g., policy decisions).

Although we will not use the rungs of the ladder as conceptual reference points in this course, the ethical and social significance of public empowerment will be a recurring theme in this course. However, it is not the only theme that we will consider, and Arnstein's ladder is not the only model that is worth considering.

Other Models of Public Engagement¶

Arnstein's ladder draws our attention to the ethical and social value of public empowerment. This is arguably a social good, but is not an unconditional good. That is, there may be cases where increased citizen control is neither desirable nor appropriate (e.g. when working with vulnerable groups, such as those with severe mental health disabilities).

As conscientious and responsible researchers, however, we may still wish to do better than mere tokenism and also avoid complete non-participation. In such cases, it is important to have a clear understanding of what our goal for public engagement ought to be. In an article reviewing different approaches to science and technology communication, Bruce Lewinstein identifies four models, which can help us to better understand the goals of public engagement [@lewenstein2003]:

- The Deficit Model

- The Contextual Model

- The Lay Expertise Model

- The Public Participation Model

The Deficit Model¶

The first of these models reflects an assumption that public awareness of and knowledge about science and technology is, in general, poor. Public surveys are often cited in support of such a view, including claims such as the following:

Quote

[...] only 10 percent of Americans can define "molecule," and that more than half believe that humans and dinosaurs lived on the Earth at the same time.

From this starting point, those who adhere to the deficit model presume that attempts to improve public knowledge are invariably a good thing.

But are they?

Why, for example, do members of the public need to know that the luminosity of the Andromeda galaxy is \(~2.6×10^{10}\) \(L_☉\), or that variational autoencoders are popular types of generative models in artificial intelligence? Moreover, why should the absence of this knowledge be treated as a deficit when it is likely to have no application in the daily lives of members of the public?

The Contextual Model¶

The way we respond to information differs depending on the context in which it is presented. Our personality type, for example, may affect how we perceive and evaluate risk. Social and cultural attitudes affect levels of trust in scientific authority. And, the media can play a substantial role in shaping our interest in science and technology—Carl Sagan, for example, was highly renowned for the passion and excitement he was able to generate in often complex or dry scientific topics.

The second model Lewinstein describes—the contextual model—therefore, recognises the need for tailoring information to specific audiences. This helps to address the deficit model's own deficit, as describe above. However, we may think that this revised model is just a more sophisticated version of the deficit model—old wine in a new bottle! After all, there is still a presumed gap in understanding, but it needs to be addressed in a specific way.

What these two models share is their presumed equivalence of 'public understanding of science and technology' with 'public appreciation of the benefits provided by science and technology to society'. In other words, the more that members of the public understand about science and technology the more they will come to appreciate its benefits.

This may be true in some instances. And so the goal of enhanced literacy ought to be recognised as a valid objective for public engagement. However, public engagement under these two models reduces engagement to a uni-directional form of communication in which the goal of the scientist is simply to inform and educate. It is for this reason that such forms of engagement fall under the 'non-participatory' category of Arnstein's ladder.

The Lay Expertise Model¶

Turning the spotlight of attention back onto the scientific communities, a further concern with the previous two models that Lewinstein identifies is that they do not adequately address the social or political contexts in which science and technology are developed, including the conflicts of interest that scientific pursuits may have with local communities or expertise (e.g. labour groups).

Far from being the sole arbiters of knowledge and expertise, scientists often fall prey to their own biases or limited perspective (i.e. positionality) and overlook diverse forms of knowledge that are rooted in local communities and practices (e.g. agriculture). Such local knowledge, including the data flows interconnected with the embedded processes of local knowledge production, may be as relevant (or even more valuable) than "technical" forms when attempting to address (or redefine) some problem.

In cases where knowledge resides in local practices and expertise, public engagement may benefit from meaningful partnerships, leading to complementary and mutually enhancing forms of knowledge. A pragmatic goal of such endeavours, therefore, is to solve problems. However, in pursuing such a goal scientists must remain vigilant that their goal and formulation of the problem is not misaligned with the goal of the communities with whom they partner.

The Public Participation Model¶

Lewinstein's final model brings us back to Arnstein's ladder. However, the topics that Lewinstein addresses go beyond empowerment to include additional benefits such as heightened public trust and consensus formation.

There are myriad activities that can support these objectives, including citizen juries, consensus building workshops, and deliberative polling. Therefore, this model also seeks to identify means for democratising science and technology in order to wrest control of research and innovation away from elite institutions and politicians.

Once we understand these different activities, it becomes clear that public participation is not about outsourcing decision-making authority to the public. In other words, the people that participate are not making decisions on behalf of researchers, but their voices should be listened to insofar as they are impacted by the consequences of a research or innovation project.

This is because scientific research and the design, development, and deployment of technology embody particular values that may not be shared by those who are directly or indirectly affected by the consequences of such activities. Obvious examples include military science and technology. Can you think of others?

The field of science and technology studies has been critically examining scientific research and practice for several decades, exposing many latent value structures and biases in the process.2 An awareness of such structures and biases is vital to understanding the goals of public engagement. We will explore this value laden nature of science and technology in relation to public engagement later. However, with this additional understanding of public engagement, let us now take a closer look at the goals of objectives of public engagement.

Who (or what) are the "Public"?

Before going any further, we should also stop to address a conceptual point about what the concept 'the Public' actually references. It is easy to fall into the trap of treating "the public" as some monolithic or homogenous entity, because of how its usage as a mass noun affects our judgement. However, as we all know, the public are a wonderfully diverse set of people, communities, and groups, of which we are a part. The more we can keep this in the forefront of our minds going forward, the less likely we will be to fall prey to myopic assumptions about public engagement.

-

A note on the terms 'participation' and 'engagement': in some cases these terms can be used interchangeably. For instance, public participation is a form of engagement. However, the reverse is not always true, as Arnstein's ladder demonstrates. For instance, informing members of the public about novel scientific results or findings through print communication is best seen as engagement, rather than than participation. This is because the reader is unable to participate in the scientific process, even if they have been engaged in the later stages (i.e. scientific communication). Throughout this guide, we will default to the use of 'engagement' where an inclusive usage is appropriate. ↩

-

For an overview of key developments in science and technology studies, see this timeline ↩