Understanding Responsibility¶

Novel technologies invariably create new and sometimes unexpected means to transgress moral and social norms.

For example, it is considered rude in many cultures to not pay attention when someone is speaking with you. However, the shift to online communication technologies, spurred on by the COVID-19 pandemic, has resulted in changing expectations about when it is deemed "rude" to not look at someone when they are speaking on Zoom. New questions arise with the adoption of new technologies.

Questions

- Is it rude to use the chat function when in a group meeting?

- Does it enable additional means for communicating that bring more people into the conversation, or does it just create distracting back channels akin to passing notes at the back of a classroom?

Addressing such questions and challenges can be difficult for myriad reasons:

Some more questions

- How can we be confident that we have reached a satisfactory, acceptable, or morally permissible conclusion?

- Which processes can we follow to help us justify and be confident in our conclusions?

- Who should be a part of the deliberative process, and are there barriers that prevent some groups from participating?

These questions are challenging and they may be answered in more than one way. Therefore, having a framework to help address them, would be incredibly useful. And this is exactly what Responsible Research and Innovation provides us with.

Responsible Research and Innovation

Responsible Research and Innovation is a framework for reflecting on, anticipating, and deliberating about the ethical, social, and legal questions that arise in the research and development of scientific and technological tools, practices, and systems.

If we could capture the essence of the motivation for RRI as a framework in a single sentence, we would be hard pressed to improve upon the following quotation:

Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral. -Melvin Kranzberg

Evaluating whether technology is likely to create harms versus opportunities, and identifying how such harms and opportunities are distributed throughout society is complicated. However, if we cannot address these challenges in a reasonable and socially acceptable manner, we will be unable to take responsibility over the research and development of disruptive data-driven technologies.

Before picking apart the concept of responsibility and its different varieties, let us first delineate the difference between two concepts often muddled together: responsibility and accountability.

Responsibility Versus Accountability¶

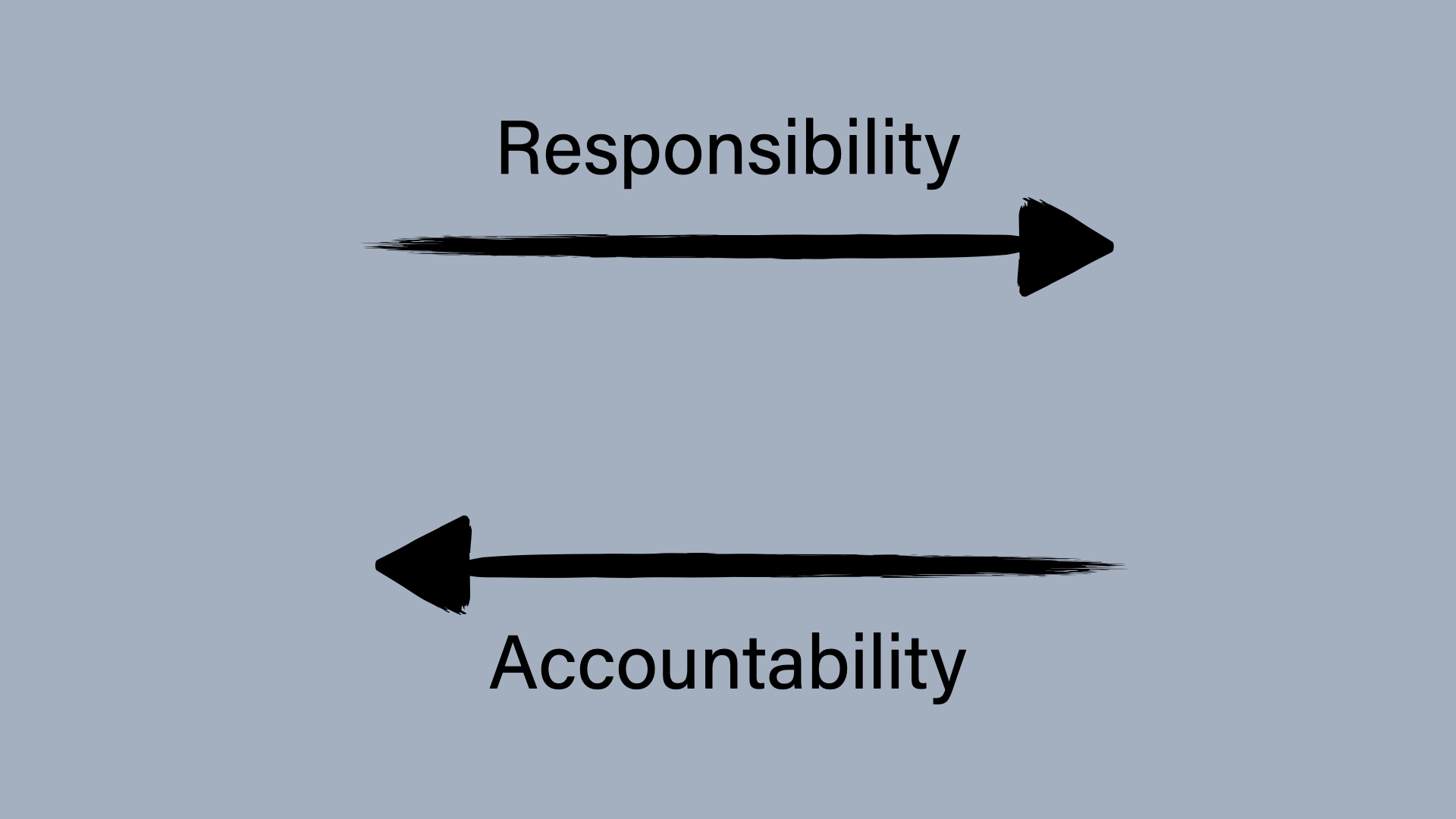

The concepts 'responsibility' and 'accountability' are often treated as synonyms in everyday conversation. However, in this module they will be treated as distinct technical terms with precise meanings. Their respective meanings will be made clear over the course of this module. For the time being though, the following graphic helps clarify an important difference.

Whereas 'accountability' is something that is applied retroactively (e.g. someone is held accountable for the consequences of their actions), 'responsibility' has a forward-looking character. That is, responsibility is an attitude, duty, or moral virtue that we take up and carry with us as we interact with others in the world.

This directionality is important. Many of the practical methods and tools discussed in this skills track have an anticipatory property associated with them. In this sense they reflect the forward-looking property of responsibility.

With a sketch of this distinction in mind, we can now start looking at the concept of 'responsibility' in more detail through two questions that will help us pick the concept apart.

Two Questions about Responsibility in Science and Technology¶

1) The Manhattan Project¶

In April 1945, Michael Polanyi—a chemist and sociologist of science—and Bertrand Russell—a philosopher and logician—were speaking on a radio programme about the practical implications of the famous formula, \(E=mc^2\).

They were asked whether the formula had any practical applications for society, but neither could provide an answer. Three months later the Manhattan project dropped the first of their three atomic bombs!

Question

Did Einstein have any responsibility for the consequences of the Manhattan Project?

2) The Harmless Torturer¶

The philosopher Derek Parfit (1984) famously offered a series of thought experiments concerning so-called “harmless torturers”.1

In the first scenario, you enter a room and see an individual strapped to a chair, connected to various pads and wires that deliver an electric current to the victim.

In front of you there is a dial with numbers ranging from 1 to 1000 that controls the electric current. You turn the dial by a single increment, increasing the electrical current so slightly that the victim is completely unable to perceive any difference in intensity.

While certainly not a morally praiseworthy action, in this first scenario you could not be plausibly held responsible for causing any harm.

However, we now run the thought experiment for a second time. In this version you turn the dial by the same small, and imperceptible, increment. But, at the same time as you do this, 999 other people turn similarly connected dials, all by one increment each.

The net result of this collective action is an intensely painful electric shock that ends up killing the restrained victim.

Questions

- What is your level of responsibility for killing the individual in the second scenario?

- Are there factors that may increase or mitigate your level of responsibility?

Now, lets's update Parfit's original thought experiment.

In this modern version, you are waiting for a bus, tired from a long day at work. You are mindlessly scrolling through a list of possible videos that have been presented to you by a recommendation system that powers your video streaming app.

You select a video of a fiery argument between two political pundits, in which one of them “destroys” their interlocutor. Ordinarily you would avoid selecting such a video, knowing that it is likely to be needlessly polarising and sensationalist. However, you’re tired and occasionally enjoy a spectacle as much as everyone else.

Unfortunately, at a similar time, 999 other individuals, with similar viewing histories to yourself also click on the same recommended video. The effect is that the recommendation system, which powers the social media platform, ends up learning that users similar to yourself and the 999 other individuals are likely to click on videos of this nature towards the end of the day. As such, in the future it will be more likely to recommend similarly low-quality, politically polarising videos to other users.

Question

Where does responsibility for the spread of content that has the potential for causing political polarisation within society lie in this example?

Types of Responsibility¶

In addition to differentiating 'responsibility' from 'accountability', we should also consider several types of responsibility.

Types of responsibility

- Moral Responsibility: all moral agents (i.e. those with the capacity for ethical decision-making) are capable of receiving praise or blame for their actions (cf. causal responsibility), especially where they are obligated to act because of some moral duty.

- Legal Responsibility: people have an obligation to act in accordance with the law. The law can compel people to act in a specific way (e.g. public sector duties) or to refrain from acting in a particular manner (e.g. civil or criminal offences).

- Professional Responsibility: the roles or responsibilities that are expected of a person in their capacity as a member of a team or organisation (e.g. to carry out research in accordance with institutional norms and best practices).

- Societal Responsibility: expectations on individuals and businesses (i.e. corporate social responsibility) to act with awareness and appreciation of social, cultural, economic, and environmental issues. Societal responsibility is often seen as demanding more from businesses than of individuals, as the former may have overriding responsibilities towards their families or local communities.

Morality and the Law¶

It is also worth drawing further distinctions between moral and legal responsibility and duties. This is because there are many legal responsibilities that data controllers and processors may have, even if these topics are outside of the scope of this module.2

Both morality and the law impose duties (or obligations) on individuals and organisations. These duties can be either positive (i.e. requiring action) or negative (i.e. requiring inaction).

However, the law tends to impose more negative duties upon individuals than positive duties, whereas morality is often more demanding. The following quotation captures this point nicely:

"Ethics is knowing the difference between what you have a right to do and what is right to do." -Potter Stewart, Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States of America

Moral philosophers refer to duties that compel action beyond what is simply permissible as 'supererogatory' duties.3 In the context of morality, one may receive praise for going above and beyond (e.g. for donating a significant portion of one's income to charity), but receive neither praise nor blame for simply acting in line with minimal obligations.

In contrast, the law tends to set the minimal threshold for acceptable behaviour while remaining silent on what constitutes morally praiseworthy behaviour. This is especially true in the context of Human Rights Law, where rights are taken to be universal in nature and, therefore, must be accepted by many different people and cultures.

NB: Duties on public sector organisations are typical exceptions to this rule. For instance, the Public Sector Equality Duty in the UK requires public sector organisations to "Advance equality of opportunity between people who share a protected characteristic and those who do not" (positive duty), as well as avoiding discrimination (negative duty).