Sociocultural Fairness¶

Data-driven technologies are not designed, developed, or deployed in a vacuum. They are embedded in a social and cultural context from which they cannot be isolated, and are created by people with perspectives that are both indicative of and constrained by their own sociocultural context.

This plurality of perspectives can problematise the fair design, development, and deployment of data-driven technologies because of the many different interpretations of what is fair. For instance, for some people, ensuring fairness will involve prioritising the reasonableness of a system's behaviour, leading to a practical emphasis on the transparency and accountability of the system's production. For others, fairness will mean prioritising the equitable impact of the system, brought about through a focus on the users that are deemed vulnerable or marginalised in the context of the system's use. While these two notions of fairness are not prima facie incommensurable in the manner introduced at the start of this module (recall Sen's example of the flute), their relative importance within a project can lead to diverging and incompatible choices in the governance of a project and implementation of a system (e.g. a highly transparent system that does not prioritise any group of users, or an opaque system that improves outcomes for a sub-group of users but in a way that is hard to explain).

This plurality can also be problematic for those wishing to learn about the fair design, development, and deployment of data-driven technologies, because it can be difficult to know where to start when attempting to get a grasp on the necessary conceptual matters. The approach adopted in this section, therefore, will be to largely focus on a sociocultural understanding of fairness. Many of the conceptual lessons learned in this section will be challenging to apply directly in practice, and in some cases you may deem it beyond the immediate responsibility of your role to try to address them (e.g. complex and systemic issues of social inequality).

If you find yourself thinking this way, then you would not be alone. The topics discussed in this section do not lend themselves to simple technical solutions. But this is sort of the point. The aim of this section is to help you understand the sociocultural context in which data-driven technologies are created, and to help you understand the sociocultural factors that can influence the fairness of a data-driven technology. Sometimes it is enough from an individual perspective to just be aware of these factors, in order to avoid doing anything to further exacerbate them. However, the more that teams and organisations do to understand and reflect on these factors, the more likely they are to be able to make a positive contribution to creating a fairer society for all.

To quote a popular 80's cartoon:

Sometimes knowing is half the battle.

Levelling the Playing Field¶

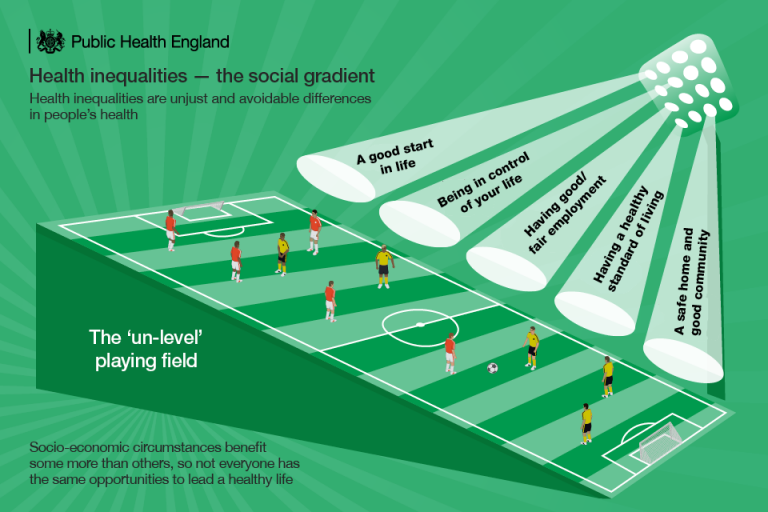

Consider the following scenario. A game of football is organised between two teams. However, on the day of the match the teams have been organised such that one team is made up of the best players, with the highest level of fitness, and with access to the best equipment. Furthermore, the football pitch is located on a field with an uneven surface, such that the gradient declines steeply towards the goal of the weaker team, and the teams do not rotate the direction of play.

How would you feel about playing this game if you were on the team with the disadvantageous conditions?

Unless you like masochistic and unreasonable challenges or find it fun to lose, you would probably not be very happy about this situation. In fact you would probably feel that the game is unfair, and you would not be alone in thinking this way. In arguing your case you would be able to point to several clear factors that make the game unfair:

- Variation in the levels of fitness between the teams

- Variation in the quality in the equipment

- Variation in the skills of the players

- An uneven playing field

Now, let's assume that the other team concedes to the (valid) reasons you have given for the game being unfair, and make certain concessions. First, they ensure everyone has access to the same equipment. Second, the match is relocated to a different field with an even surface.

However, the composition of the teams remains the same. The game goes ahead, and unsurprisingly, the disadvantaged team loses.

In this toy example, some of the factors that contribute to the initial unfairness of the game are ones that can be easily resolved (e.g. access to equipment, uneven field). But others remain harder to resolve, such as variation in skills. Some would argue here that variation in skills and fitness is a natural part of the game of football (and sports in general). As such, they would argue that the game is fair in this sense once the other factors are resolved.

But what if we delve further into the historical factors behind this variation in skills and fitness?

Perhaps the advantaged team come from a wealthy background, and have always been able to afford the best equipment and training facilities. And, perhaps the disadvantaged team have a lower level of respiratory fitness, in part, because of high levels of pollution in the area where they live.

While the game is fairer in the adjusted scenario, it's still true to say that one of the teams has been playing on an uneven field before the game even begins. It's just that the field, here, is no longer a physical one; but a sociocultural one that spans back across many years.

In relation to data-driven technologies, sociocultural fairness is about identifying the factors (or, sociocultural determinants) that precede the choices made during a project's lifecycle but which affect the overall fairness of the technology. In other words, before the game of the project lifecycle begins, how is the field already uneven and how can we level it to make sure that the game is fair? And, once the game has finished, how do the results affect future games?

There may be little motivation to address unfairness in the context of sports, but life and society are not games.

Identifying Fairness Factors¶

Let's call the factors that are identified or appealed to when identifying or evaluating the overall fairness of some event or situation, 'fairness factors'. That is, the factors that we appeal to as reasons for why something is fair or unfair. Let us also try to further distinguish between a few types of fairness factors.

For instance, in the case of the football game, there is clearly a difference between these three conditions:

- Having an uneven playing field that slopes towards one team's goal

- Variation in the skills of the players

- One team being given orange squash at half-time and the other one being given blackcurrant squash

The first condition is highly discriminatory towards one of the teams, and has no place in a fair game of football. In fact, the organising committee for this league may even have some regulation in place that prohibits this. Let's call the set of fairness factors that are similar to this one, 'impermissible factors'. In other words, such factors are never permissible in a fair game (or, project).

The second condition, in the context of sport, is still a discriminatory factor like the first because it plays a contributory role in determining or influencing the outcome of the game. However, although discriminatory in this sense, it is not necessarily unfair. Whether it is perceived as a relevant fairness factor will depend on a broader range of social and historical factors (e.g. whether the variation is itself the result of unfair patterns of discrimination). Therefore, let's call these fairness factors, 'potentially permissible factors' to highlight the need for further consideration and deliberation in evaluating their status.

And, finally, the third factor seems utterly irrelevant to the outcome of the game and should, therefore, not be considered a 'fairness factor' at all. We can, therefore, call this set of (non fairness) factors 'irrelevant factors'. Needless to say, we won't spend much time on this final set.

Equality Act 2010 and protected characteristics

The UKs [Equality Act 2010](https://www.gov.uk/guidance/equality-act-2010-guidance) makes it illegal to discriminate against someone because of a protected characteristic. The set of protected characteristics are

- age

- disability

- gender reassignment

- marriage and civil partnership

- pregnancy and maternity

- race

- religion or belief

- sex

- sexual orientation

Such characteristics are often used as proxies for what we are calling 'impermissible factors'.

That is, they cannot be used (either directly or indirectly) as a means for discriminatory or prejudicial treatment.

We will return to these factors in the next section.

Differentiating between the three sets of factors in this way helps draw attention to the importance of public reason giving, deliberation, and justification in the context of fair design, development, and deployment of data-driven technologies. That is, in many cases it will not be sufficient to just identify those factors that are impermissible due to some legal or regulatory requirement (e.g. protected characteristics). In the remainder of this section, we will help illustrate this point by looking at three use cases of data-driven technologies, which intuitively seem to be unfair but where this may not arise due to some simple or easily identifiable 'impermissible factor'.

The Digital Divide (Who Gets to Play the Game?)¶

In our running analogy, one of the football teams had access to better equipment and training facilities. The other team, in contrast, do not have the same access to high-quality resources. As such, while both teams are able to train in principle, it is likely that the team with access to better resources will be able to train more effectively or efficiently.

Question

Are there barriers to access that prevent some people from participating at the same level as others?

Barriers to accessing resources, in the context of data-driven technologies, are factors that contribute to what is commonly referred to as the digital divide. In short, this term refers to the gap between those who have access to digital technologies and those who do not, as well as the varying levels of access in-between.

A digital divide can exist in many forms, including:

- Differential access to the internet (e.g. variation in speed and reliability, barriers from higher costs)

- Differential access to compute resources (e.g. faster processors, more memory, etc.)

- Variation in digital literacy and skills (e.g. ability to think critically about online content, ability to manipulate data)

Evaluating the sociocultural fairness of data-driven technologies requires us to explore holistic factors that are not always directly linked to the outcomes of the technology itself. Perhaps a team of developers are building an online app that recommends free activities in their local neighbourhood and uses data about their interactions to improve these recommendations over time. To improve the security and data protection properties of the app, the developers decide to use edge computing techniques1 to process the data locally on the user's smartphone—thereby enhancing the user's privacy. However, this design choice builds in a requirement that use of the app will require a smartphone with a certain level of processing power. In addition, the recommendations depend on a strong base of users in the local area, which may not be the case in some neighbourhoods.

As such, two seemingly innocuous (and perhaps initially desirable) factors nevertheless create a divide that prevents some people from using the app.

Fairness factors that are related to the digital divide are often raised under the banner of accessibility concerns. And, although there are some legal requirements or regulatory precedents that compel organisations to proactively consider and improve accessibility, because so many 'digital divides' arise without explicit forms of impermissible discrimination, they often go overlooked.

Poverty

Epidemiologists and social scientists have long recognised that poverty is a key factor in determining outcomes in many areas of life (e.g. health, education, employment).

But, poverty is not a protected characteristic, and as such, despite many technologies implicitly discriminating against wide areas of society on the basis of economic conditions, there are few legal protections in place to ensure the use and implementation of technologies do not create unfair impacts on those who are already economically disadvantaged.

To be clear, not all barriers to access constitute impermissible factors. For instance, some systems or services may specifically target a group of people who are disadvantaged in some way (e.g. a web browser plugin that improves accessibility for people with visual impairments). This creates a barrier, in some sense, to the group of non-users who would not benefit from the technology. But it is hardly a barrier that many would consider unfair.

Understanding and evaluating the socio-cultural fairness of data-driven technologies, therefore, requires us to consider whether any barriers exist that prevent people from using the technology, and whether these barriers are permissible or not.

Question

Are any groups unfairly excluded from using the technology or benefiting from its use?

Ghost Labour (Who Built the Field?)¶

Before our game of football can begin, the field has to be prepared by a team of groundskeepers (whose work, we shall assume, is often invisible to the players). The previous question of 'who get's to play the game' is, therefore, one that presumes the existence of a playable location, which connects us to our next topic of sociocultural fairness.

Question

Who is responsible for maintaining the field, and is their labour fairly compensated?

In the context of data-driven technologies, especially those that purport to demonstrate artificial intelligence, a lot of the groundwork is done by teams of data cleaners, labellers, or annotators. In some cases, this falls on the shoulders of junior members of a research team (e.g. research assistants). In other cases, this tiring and laborious work is carried out by ghost labourers—people who work behind the scenes and are, typically, paid miniscule amounts for their work.

The example of OpenAI's ChatGPT model is a good example of this latter kind of work, and also illustrates another factor related to ghost labour: extraction of value from the work of others. In January 2023, a Time article reported that OpenAI—the company that developed ChatGPT—used outsourced Kenyan laborers earning less than $2 per hour to help train the model by tagging and labelling data that was deemed toxic or offensive. While the end goal here may be laudable, the means by which it was achieved raises clear red flags about the fairness of developing such a model in the first place. Furthermore, the initial data used to train ChatGPT (and other models in OpenAI's library) depends on the availability of large amounts of data that is freely available on the internet. While these data are 'public', and, therefore, likely permissible to reuse by others, the fact that they are freely available is, in part, a result of the work of others who are not compensated for their efforts.

Understanding and evaluating the sociocultural fairness of data-driven technologies, such as AI, require us to consider the ghost labour that enables them to demonstrate "intelligent" capabilities.

Question

How should the people whose labour is responsible for the development of data-driven technologies be fairly compensated?

Representation (How are the Different Teams Represented?)¶

Returning to our running analogy, for the final time, and stretching the analogy to its very limits, let us consider how each of the teams were represented leading up to the game. Let's pretend that because of their ongoing success one of the teams has a large marketing budget and receives the best form of media representation. While this may not directly affect the outcome of the game, it has certainly been something that the team have long found appealing and motivating. In contrast, the other team has no marketing budget and have to rely on whatever coverage they receive, much of which is negative or false.

Question

There is a clear difference in the way that the two teams are *represented*. Is this difference unfair?

This final theme is different from the others we have considered so far. Differential representation can lead to harmful physical consequences, such as a patient receiving the wrong treatment due to being misclassified by an algorithmic triaging system, or a person being wrongly sentenced to time in prison due to a biased algorithmic risk assessment system. But, fair representation matters in its own right. That is, whether certain groups of people are more or less likely to be represented by a technology in a way they perceive to be fair is an issue with intrinsic value, and is independent from whether the mis-representation leads to harmful outcomes. To see why, let's first consider the set of data-driven technologies that are used to classify people into groups.

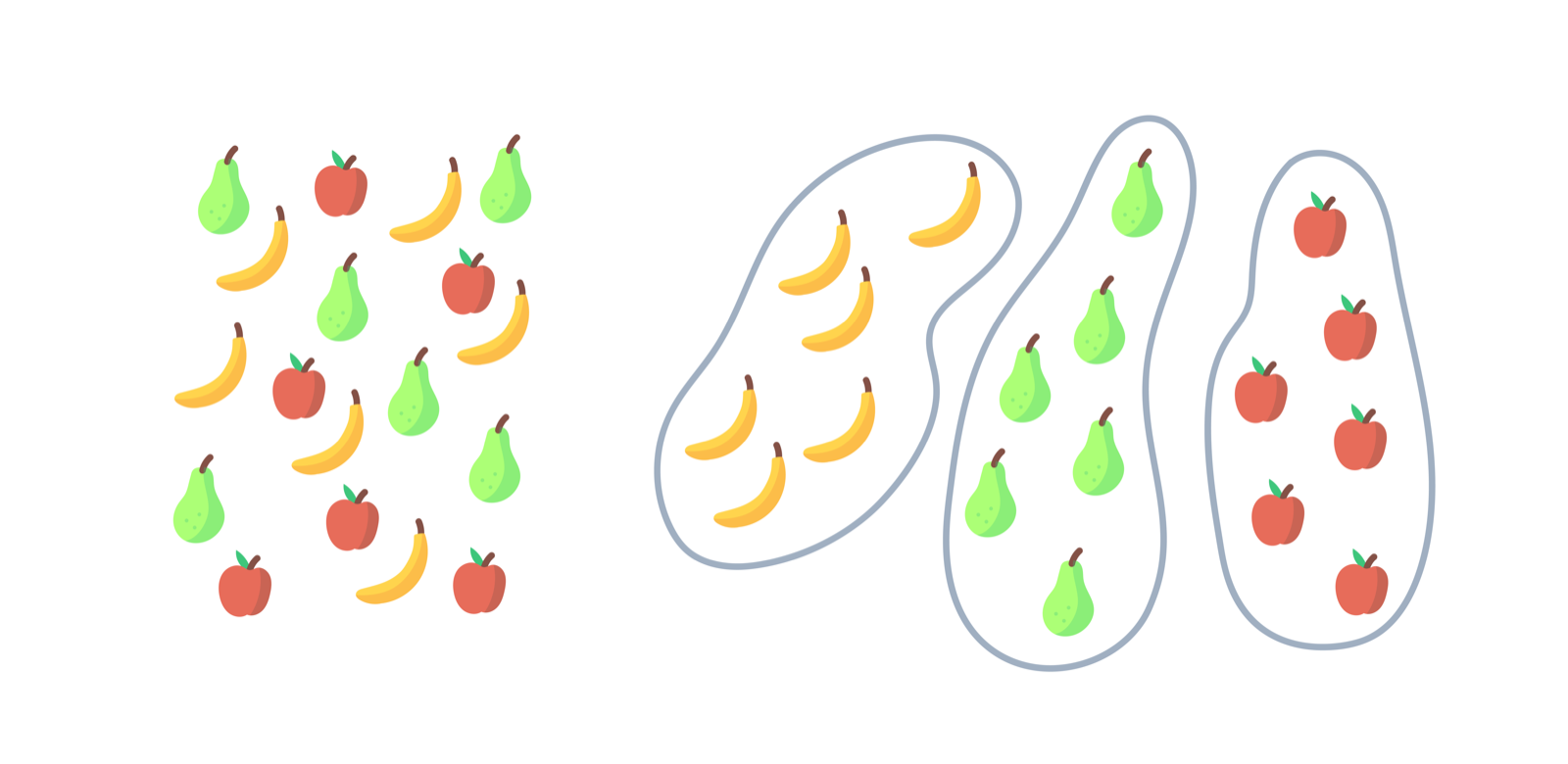

Many data-driven technologies sort and classify people and objects into groups. Some do this as a result of categories pre-selected by humans (e.g. demographic variables in a census), whereas others attempt to use forms of machine learning to organise people or objects into groups (or buckets) that are represented via a set of labels. In the context of objects, like the fruit below, the labels we choose will have no effect on the objects themselves. A banana will not mind if we call it a 'wonky yellow thing'.

The same cannot be said for humans.

Try to think about the last time you felt as though you were either unfairly represented, or anxious about how other people saw you. Perhaps you want to be seen by your manager and colleagues as a hard-working and diligent employee. Maybe you worry that your friends do not think you are loyal, or that you are not a responsible and loving parent. Regardless of the underlying truth, the way that we perceive ourselves and the way that others perceive us is an important part of our identity and overall sense of well-being.

So, now imagine that you find out that an organisation has an algorithm that automatically decides you are not worth showing job adverts for senior positions to, or that your interests on social media suggest you may be interested in counselling services.2 Your misrepresentation in these examples may not be causing any immediate physical harm, but many would agree that there is something inherently unfair about this mis-representation and the systemic mis-representation of groups of people like you.

The reasons you may give in explanation of this perceived unfairness will likely differ from those given by others. Some may emphasis matters of human dignity as a core motivating value in rationalising their position. Others may draw attention to the fact that some labels may perpetuate psychologically harmful stereotypes. Others still may emphasise the moral value of freedom of self-determination.

For our present purposes it is not necessary to weigh or evaluate the relative importance of these myriad reasons. What matters here is that we recognise that understanding and evaluating the sociocultural fairness of data-driven technologies, such as AI, requires us to consider the way that they inevitably represent individuals and groups of people, and whether these representations are inherently fair.

Question

How do those represented (and classified) by data-driven technologies perceive and judge the inherent fairness of these representations?

Meaningful Stakeholder Engagement

This section has focused on introducing some important conceptual distinctions, and, therefore, has largely set aside practical considerations (albeit temporarily).

We will address this limitation in the coming sections, but two important points are worth mentioning here.

First, one of the primary means for identifying and evaluating fairness factors that are relevant to a particular data-driven technology is through stakeholder engagement.

Furthermore, determining whether their influence on a project or system is permissible or impermissible will likely involve a similar process (e.g. consulting domain experts, seeking feedback from affected users).

A key challenge here is resolving differences between separate groups who will inevitably disagree on whether some factor is fair or not (i.e. permissible or impermissible influence on the design, development, and deployment of data-driven technologies).

However, and to the second point, stakeholder engagement can itself present barriers to accessibility for some groups.

For instance, if you choose to carry out stakeholder engagement workshops through a video conferencing platform, you may (unintentionally) create a digital divide that excludes those who do not have access to the internet or a computer.

Discussing these points in sufficient detail is beyond the scope of this section and module.

However, if you are interested in exploring how to design and facilitate responsible forms of public and stakeholder engagement, we have a [separate skills track](#) that addresses these topics in the context of data science and AI projects.

-

Edge computing is a distributed computing paradigm which brings computation and data storage closer to the sources of data, such as for example IoT devices or local edge servers. ↩

-

There have been real-life instances on both of these cases. For example, in 2015, it was reported that female job seekers were much less likely to be shown highly paid job adverts on Google than men did. On a more personal note, in this article, the author reflects on the amount of content on grief and loss they received, after some Google searches on the topic. ↩