Understanding the Assurance Ecosystem¶

In 2021, the UK Government's Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation released their AI Assurance Roadmap. This publication set an agenda and series of recommendations for how to build and govern an effective AI Assurance ecosystem.

In the context of AI, we can think of an assurance ecosystem as the framework or environment that encompasses the methods, tools, roles, responsibilities, stakeholders (and relationships between them) that collectively work towards ensuring AI systems are designed, developed, deployed, and used in a trustworthy and ethical manner. As such, it is an emerging concept, which is currently only loosely defined but can, nevertheless, help us address the challenges posed by AI technologies and maximise their opportunities.

CDEI's AI Assurance Guide

The following is based on and adapted from the Centre for Data Ethics and Innovation's AI Assurance Guide, which extends their original roadmap and seeks to clarify the scope of an assurance ecosystem as it pertains to AI. We consider some of the core concepts of the CDEI's guide, focusing on the parts that are relevant to the TEA platform. For further information, please visit their site: https://cdeiuk.github.io/ai-assurance-guide/

Why is Assurance Important¶

Data-driven technologies, such as artificial intelligence, have a complex lifecycle. In some cases, this complexity is further heightened by the scale at which a system is deployed (e.g. social media platforms with international reach).

The scale and complexity of certain data-driven technologies has already been clearly communicated by others, such as this excellent infographic from the AI Now Institute showing the many societal impacts and touch points that occur in the development of Amazon’s smart speaker. Therefore, it is not necessary to revisit this point here. However, it is important to explain why this complexity and scale matters for the purpose of trustworthy and ethical assurance. There are three (well-rehearsed) reasons that are salient within the context of the assurance ecosystem:

- Complexity: as the complexity of a system increases it becomes harder to maintain transparency and explainability.

- Scalability: the risk of harm increases proportional to the scale of a system, and mechanisms for holding people or organisations accountable become harder to implement.

- Autonomous behaviour: where data-driven technologies are used to enable autonomous behaviour, opportunities for responsible human oversight are reduced.

Justified Trust¶

As discussed at the start of this section, assurance is about building trust.

But there is a further concept, related to trust, which is vital for assurance: trustworthiness.

As the CDEI's guide acknowledges:

"when we talk about trustworthiness, we mean whether something is deserving of people’s trust. On the other hand, when we talk about trust, we mean whether something is actually trusted by someone, which might be the case even if it is not in fact trustworthy." A successful relationship built on justified trust requires both trust and trustworthiness: Trust without trustworthiness = misplaced trust. If we trust technology, or the organisations deploying a technology when they are not in fact trustworthy, we incur potential risks by misplacing our trust. Trustworthy but not trusted = (unjustified) mistrust. If we fail to trust a technology or organisation which is in fact trustworthy, we incur the opportunity costs of not using good technology.

The concept of justified trust is, understandably, an integral part of trustworthy and ethical assurance.

We can turn to the moral philosopher, Onora O’Neill, for a clear articulation of why this is so,

“[...] if we want a society in which placing trust is feasible we need to look for ways in which we can actively check one another’s claims.

But, she continues,

“[...] active checking of information is pretty hard for many of us. Unqualified trust is then understandably rather scarce.”

The CDEI's Assurance guide identifies two problems that help explain why active checking is challenging:

- An information problem: organisations face difficulties in continuously evaluating AI systems and acquiring the evidence base that helps establish whether a system is trustworthy (i.e. whether users or stakeholders should place trust in the system)

- A communication problem: once they have established the trustworthiness of the system, there are additional challenges to communicate this to relevant stakeholders and users such that they trust the claims being made.

An effective assurance ecosystem should help actors overcome these issues to establish justified trust. Let's take a look at some of the key actors in an assurance ecosystem.

Key Actors, Roles, and Responsibilites¶

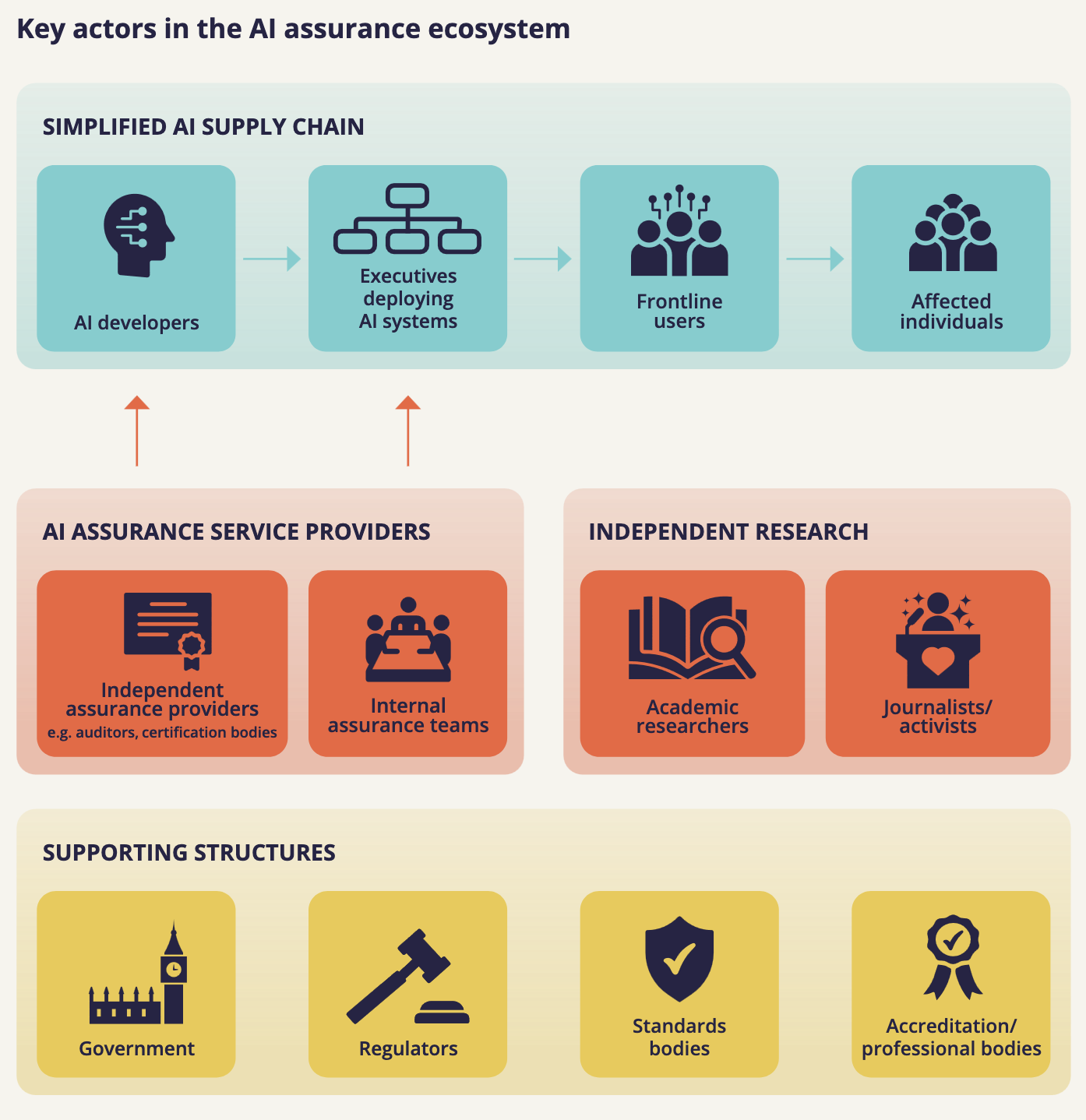

AI is often described as sociotechnical. Here, the term "sociotechnical" is used to emphasise how the design, development, deployment, and use of AI is deeply intertwined with social systems and practices, and influenced by a wide array of human and organisational factors. Because of this, any list of actors, and their various roles and responsibilities will fall short in a number of dimensions. However, the following graphic provides us with a good starting point for understanding the key actors in an assurance ecosystem.

Figure 2. Key actors in the AI Assurance Ecosystem. Reprinted from CDEI (2023)

AI Assurance Guide.

https://cdeiuk.github.io/ai-assurance-guide/needs-and-responsibilities

Figure 2. Key actors in the AI Assurance Ecosystem. Reprinted from CDEI (2023)

AI Assurance Guide.

https://cdeiuk.github.io/ai-assurance-guide/needs-and-responsibilities

As the diagram depicts, certain actors have a direct influence into the supply chain for AI systems. These are known as 'assurance users'. For instance, organisations may have dedicated teams internally who are responsible for quality assurance of products or services (e.g. compliance with safety standards, adherence to data privacy and protection legislation). However, there is a growing marketplace of independent 'assurance service providers' who offer consultancy or services to other companies or organisations.1

These users and providers are further supported by structures including governments, regulators, standards bodies, and accreditation/professional bodies. That is, the relationship between users and provides does not operate in a vacuum, but within a complex environment of legislation, regulation, and general norms and best practices.

This is a helpful starting point for gaining some purchase on the complex set of interacting roles and responsibilities that collectively make up what is admittedly a hard to delineate assurance ecosystem. Because the TEA platform emphasises the importance of ethical reflection and deliberation, the resources and materials are likely to be of specific interest to the following actors:

- Researchers

- Journalists/Activists

- Internal Assurance Teams

- Developers

- Frontline User

- Affected Individuals

Assuring different subject matter¶

Whether someone needs to build confidence in the trustworthiness of different products, systems, processes, organisations or people will influence the type of information required, and the techniques required to provide assurance. This is because different products, systems, processes, organisations and people have different aspects that affect their trustworthiness i.e. they have different assurance subject matters.

Whether a frontline user of a system is confident in using the system will depend on a wide variety of factors. If the system is a medical device, and the frontline user is a healthcare professional, safety and accuracy may be primary concerns. However, if the system is an algorithmic decision-support tool, the frontline user may care more about the explainabilty of the system.

Assurance needs, therefore, vary depending on what's being assured—products, systems, processes, organisations, or individuals. Simple products like kettles may have straightforward, measurable assurance criteria, whereas complex systems like AI necessitate nuanced, multi-dimensional assurance approaches due to their varied subject matters like robustness, accuracy, bias, explainability, and others. As previously noted, the complexity of AI arises because of the sociotechnical interactions between technical, organisational, and human factors. Ethical principles such as fairness, privacy, and accountability are intertwined with these interactions, necessitating comprehensive assurance mechanisms.

While not specifically designed to address ethical principles, the following diagram from the CDEI's Assurance Guide can help elucidate some of the reasons why trustworthy and ethical assurance can be challenging.

Figure 3. A graphic showing the four

dimensions of assurance subject matter: unobservable/observable,

subjective/objective, ambiguous/explicit, uncertain/certain.

Figure 3. A graphic showing the four

dimensions of assurance subject matter: unobservable/observable,

subjective/objective, ambiguous/explicit, uncertain/certain.

- In the context of the TEA platform, the different subject matter represent the domain of the assurance case, summarised in the top-level goal claim (e.g. fairness).

To what extent does the TEA methodology and platform align with the CDEI's 5 elements of assurance: https://cdeiuk.github.io/ai-assurance-guide/five-elements →

-

For example, Credo AI offer a paid-for service that comprises an interactive dashboard and set of tools to help companies comply with existing and emerging policies and regulation. Whereas, other organisations, such as the Ada Lovelace Institute have developed open-source tools for teams to implement within their own projects. ↩