Machine learning transparency

Contents

1.4. Machine learning transparency¶

Transparency is a fundamental AI ethics principle key to responsible AI innovation [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021]. It plays a crucial role in the development of ML systems, as well as in the evaluation of their performance and the trust that people place in them. We follow the definition and framework of transparency in [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] in this course.

1.4.1. Why is transparency important?¶

For ML systems to be trustworthy and to be used responsibly, it is vital to ensure that they are transparent, i.e. stakeholders have access to information relevant to them. Addressing concerns of AI and preventing potential harms of AI requires information being available to individuals involved in designing an ML system, developing it, deploying it, and using it, as well as to the general public, regulators, and other stakeholders for them to understand decisions made by the system, trust it, and hold it accountable. Different stakeholders are likely to have different information needs.

Transparency and accountability are closely related and reinforce each other. Accountability mechanisms depend on the availability of information about an ML system and accountability is key motivation for transparency. Transparency also acts as an enabler to other ML/AI ethics principles including fairness, sustainability, and safety.

In the context of research, transparency is important if you want to interpret the results of your ML system, and understand how it works. It is also important if you want to explain the results to your research community, and it can even help you verify your results.

1.4.2. What is transparency?¶

ML transparency relates to disclosing information about ML systems, and it can be understood as relevant stakeholders having access to relevant information about a given ML system. Transparency involves gathering and sharing information about an ML system’s logic (i.e. explainability) and how it was designed, developed, and deployed.

The three key questions to ask when considering transparency are:

What types of information are relevant?

Who are the relevant stakeholders?

Why are stakeholders interested in information about an ML system?

Transparency is a property of the system, and it is not a property of the information itself. Transparency is a relative concept, and it is not an absolute concept. Transparency is context-dependent and it is not a fixed property of the system. For example, a system transparent to a doctor (data scientist) does not mean the system is transparent to a patient (customer). External stakeholders (e.g. regulators, the general public) may have different information needs than internal stakeholders (e.g. data scientists, developers, and engineers).

1.4.3. Relevant information¶

There are two broad categories of information considered relevant for transparency:

System logic information: Information that relates to the operational logic of a given ML system, i.e. information about the system’s ‘inner workings’. Examples include information about the input features that a system relies on or information about the relationship between the system’s inputs and outputs.

Process information: Information that relates to the processes surrounding the ML system’s design, development, and deployment. Examples include information about data management practices, assessments of system performance, quality assurance (including of data) and governance arrangements, or the training of system users.

Respectively, the above categories of information define two forms of transparency:

System transparency: Stakeholders having access to system logic information

Process transparency: Stakeholders having access to process information

In this course, we will study machine learning systems from the perspectives of these two forms of transparency, briefly discussed below, with more details available in appendices on System transparency and Process transparency.

1.4.4. System transparency¶

System transparency refers to access to information about the operational logic of a system. The most transparent systems are simple systems where system logic information can be inferred purely from a system’s formal representation. Three types of information are considered relevant for system transparency:

(1) The input variables that a given system relies on: what are the types of information that the system uses in operation?

(2) The way in which the system transforms inputs into outputs: what is the relationship between input variables and system results?

(3) The conditions under which the system would produce a certain output: for what values of the input variables would the system return a specific value of interest?

See Appendix System transparency on more details about such info, why these three types of information are considered relevant for system transparency and how to obtain and communicate such info.

1.4.5. Process transparency¶

Process transparency concerns access to any information about an ML system’s design, development, and deployment apart from the system’s logic. As with system logic information, such process information is important for addressing and providing assurance about concerns raised by AI systems. Correspondingly, there is a growing amount of work on how process information can be recorded, managed, and made accessible in practice.

We can categorise process information regarding ML systems along two dimensions:

Different lifecycle phases: Process information can relate to (i) the design and development or (ii) the deployment of an ML system. In both areas, more specific lifecycle phases can be distinguished, each of them associated with unique aspects of information.

Different levels of information: In considering a given lifecycle phase, different levels of process information can be distinguished, corresponding to the kinds of questions that the information serves to answer.

See Appendix Process transparency on more details about such info, why such information is considered relevant for process transparency and how to manage such info.

1.4.6. Relevant stakeholders¶

The information that is relevant to a given stakeholder depends on the stakeholder’s role and the context. For example, a data scientist may need to know the details of the data collection process, while a data subject may need to know how their data is used. We can split those who may have an interest in system or process transparency into two categories:

Internal stakeholders: Those individuals who are involved in the design, development, and procurement of the ML system. Examples include data scientists, developers, and engineers. They also include individuals who make decisions about its deployment, operate the system, manage external communications, or perform corporate governance and oversight functions. Examples include members of development or procurement teams, risk and compliance teams, audit teams, senior management, company boards, operational teams using the ML system, and customer service teams.

External stakeholders: Those individuals who are external to the organisation employing the ML system that have a significant relationship with the organisation deploying the system or may be affected by the ML system’s use. They are not involved in the design, development, procurement, and deployment of the ML system. Examples include regulators, customers, shareholders, academics, and the general public.

Based on these two categories of stakeholders, we can make a second distinction in mapping out different types of transparency:

Internal transparency: Information being accessible to internal stakeholders

External transparency: Information being accessible to external stakeholders

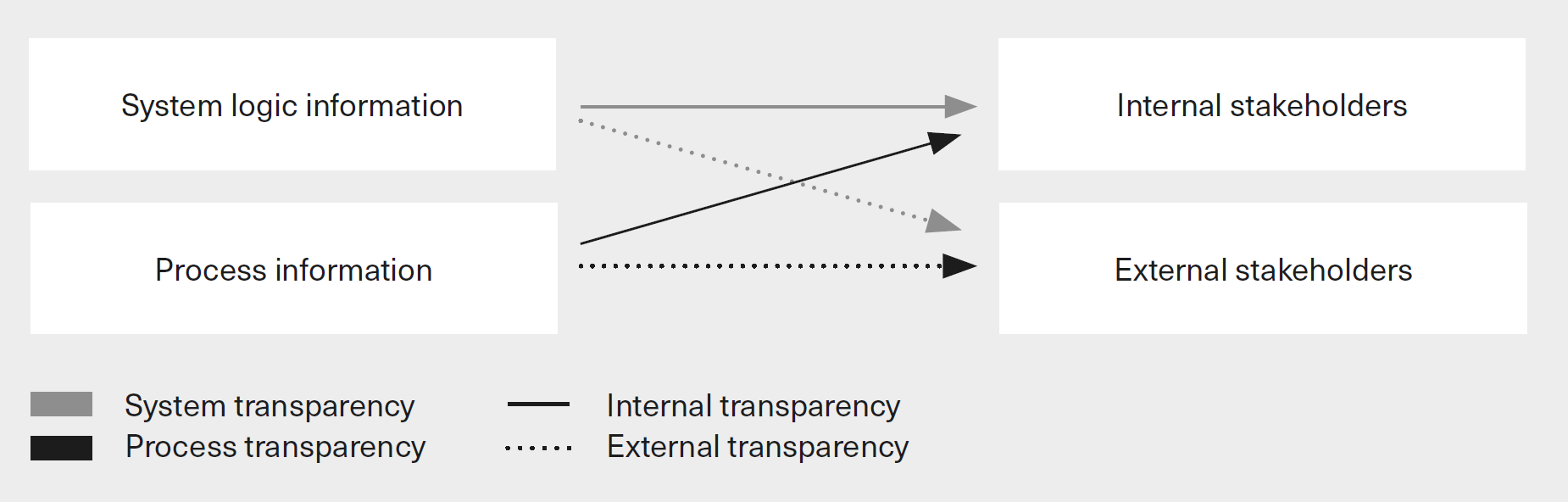

This second distinction intersects with the first one, between system and process transparency. System logic information or process information can be accessible to internal stakeholders, external stakeholders, or both. The resulting four-fold transparency typology is summarised in Fig. 1.4 below.

Fig. 1.4 AI transparency typology [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

1.4.7. Reasons for accessing information¶

As mentioned above, transparency is a relative concept. Not all types of information about an ML system will be equally important to all types of stakeholders. The reasons that underpin stakeholders’ interests in information about a given system (i.e. their ‘transparency interests’) are important in determining the types of information they may seek access to. When these reasons differ between stakeholders, the definition of what constitutes relevant information can change. For example, customers faced with an ML system used to make credit eligibility decisions may wish to understand the impact of, say, a 3% pay raise on their credit eligibility. The answer to this question can involve types of information that may not be relevant to the transparency interests, say, of regulators, which may be motivated by the goal of understanding different aspects of system performance and compliance.

Stakeholders’ transparency interests can differ even when their reasons for seeking information are the same. For example, a risk and compliance officer may seek information about an ML system for the same reasons and look for answers to the same questions as a different internal stakeholder (eg a customer service representative) or an external stakeholder (eg a member of the public). Each of these stakeholders, however, might expect different levels of detail.

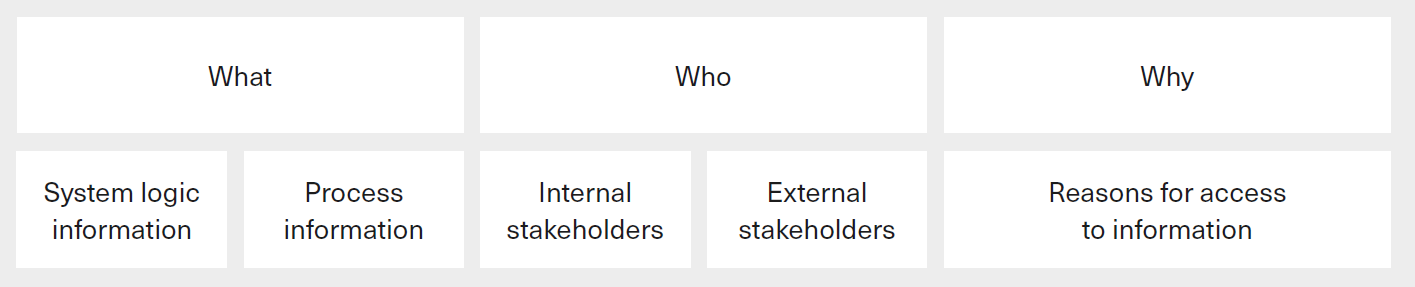

Figure Fig. 1.5 summarises the three key questions of AI transparency so far.

Fig. 1.5 Summary of the three key questions of transparency [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

1.4.7.1. Interpretability-flexibility trade-off¶

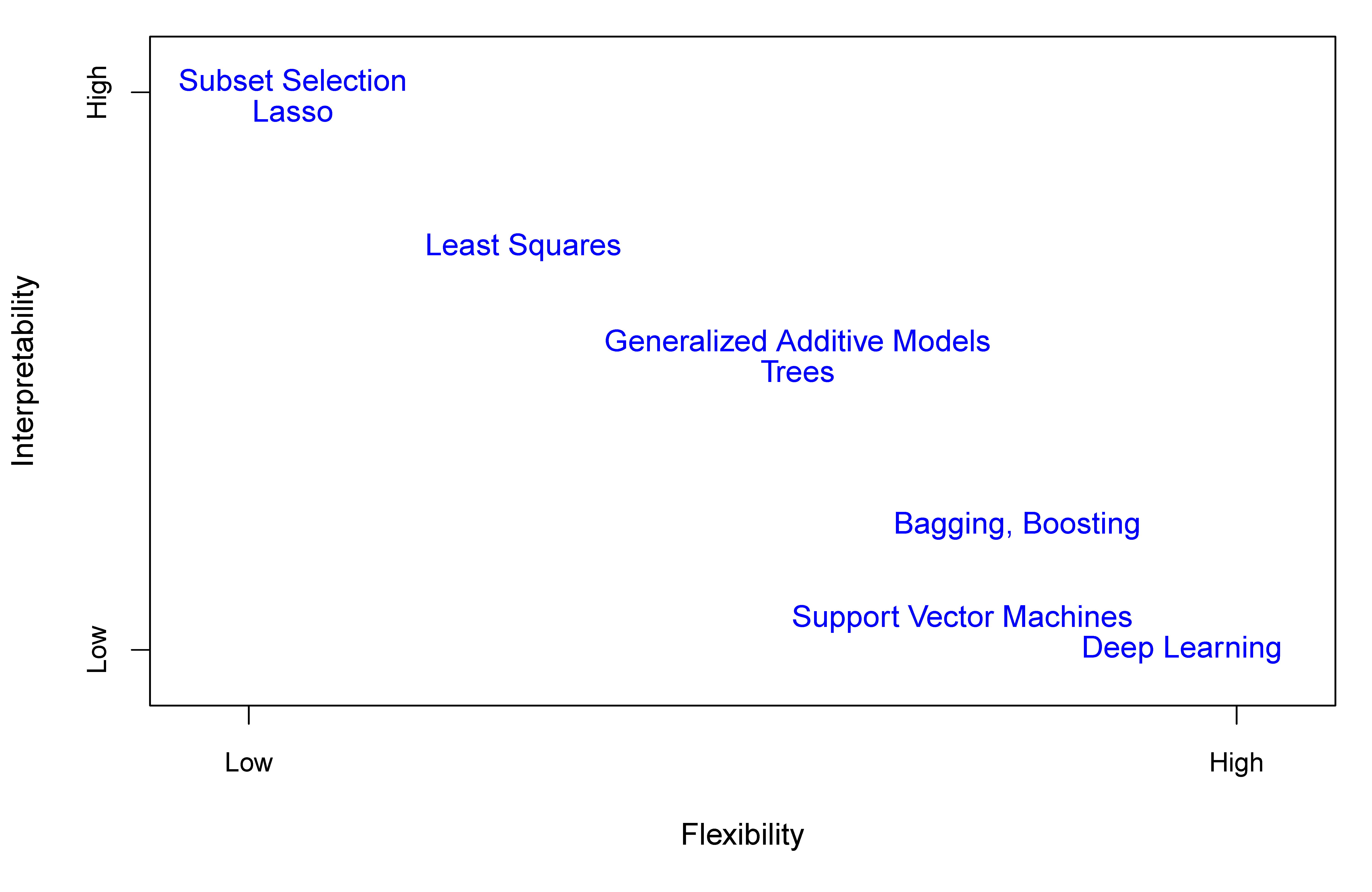

In general, linear models allow for a more interpretable (but less flexible) model, while nonlinear models allow for a more flexible (but less interpretable) model.

A trade-off between model flexibility and interpretability is shown in the figure below.

Fig. 1.6 A trade-off between model flexibility and interpretability [James et al., 2021].¶

The decision to limit model complexity for the sake of interpretability is often portrayed as a tradeoff with model accuracy. You may find figures look like the above but replacing flexibility with accuracy. The basis for this argument is the assumption that more complex models have higher accuracy than simpler ones. Yet, this assumption is not always true. In many modelling contexts, interpretable models can be designed to achieve the same or comparable levels of accuracy as models that would be considered uninterpretable. Significant research efforts are underway to advance the field of interpretable machine learning. Over time, these research efforts can be expected to further reduce the range of contexts in which interpretability-accuracy tradeoffs are perceived to exist.

Decisions in favour of interpretability do not necessarily come at the expense of accuracy. Where trade-offs between interpretability and accuracy do exist, it may be preferable to accept a lower level of accuracy in the interest of enabling direct interpretation by system developers and other relevant actors. Conversely, where uninterpretable models are being used, it is important to be mindful of the limitations of explainability methods. Ignoring these limitations risks having a false sense of understanding, potentially resulting in misplaced trust in ML systems and unexpected harmful outcomes. Governance arrangements play a key role when it comes to choosing appropriate types of models.

1.4.8. Other trade-offs¶

There can be reasons for not making some types of information about ML systems accessible to certain stakeholders. Such reasons often play a prominent role in discussions about the disclosure of information to external stakeholders in particular. The applicability of such countervailing reasons is context dependent. In particular, these reasons, where relevant, do not speak against the disclosure of system logic and process information in a wholesale manner. Instead, they typically apply to the disclosure of specific types of information (e.g. specific aspects of system logic information rather than all types of system logic information) to specific types of stakeholders (e.g. customers rather than all external stakeholders), for specific types of use cases.

In addition, disclosing information that is irrelevant or excessively detailed in response to stakeholders’ questions may generate undue distrust. Avoiding ‘information overload’ is one possible reason against the disclosure of some types of information to certain stakeholders.

Three other potential reasons are worth noting:

Preventing system manipulation or ‘gaming’: In some cases, firms employing ML systems may seek to protect certain aspects of information to prevent the subversion of these systems. In the case of fraud detection systems, for instance, preventing adversarial actors from finding ways to evade detection can speak against disclosing information about system logic or the data used to customers. Yet, this countervailing reason does not necessarily apply to the disclosure of the same information to regulators, or the disclosure of other types of information to customers.

Protecting commercially sensitive information: Certain types of information may be considered commercially sensitive by the firm employing an ML system or by third-party providers involved in the system’s development. For example, an investment management firm that relies on proprietary ML systems to identify profitable investment opportunities has an interest to protect the competitive advantage enabled by these systems. Similarly, third-party providers may want to protect the IP contained in their products. As such, firms may be reluctant to disclose information that is central to their commercial success. Once again, however, this reason typically only applies to specific types of information (eg details of a system’s logic or proprietary source code) and their disclosure to certain stakeholders.

Protecting personal data: Certain forms of information disclosure can conflict with firms’ obligation to protect personal data. This includes, most obviously, the direct sharing of personal data – be it data used in the development or the operation of ML systems – in ways that violate data protection legislation. In addition, where ML systems are trained with personal data, it may be possible to infer protected personal information through, for example, model inversion or membership inference attacks. While concerns about such attacks only apply in limited circumstances, they can speak against the disclosure of certain aspects of system logic information to stakeholders.

The applicability and implications of transparency trade-offs depend on context and vary between use cases. Regardless of the applicability of different countervailing reasons, large segments of the information that is of interest to stakeholders will remain unaffected.

1.4.9. Exercises¶

1. Transparency is the key motivation for accountability.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

b. False. Accountability is a key motivation for transparency

2. Transparency acts as an enabler to other ML/AI ethics principles.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

a. True

3. Transparency is a property of the information.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

b. False. Transparency is a property of the system.

4. Transparency is not a fixed property of ML systems.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

a. True

5. Deep learning models has high interpretability but low flexibility.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

b. Deep learning has high flexibility and low interpretability.

6. Stakeholder’s transparency interests can differ even when their reasons for seeking information are the same.

a. True

b. False

Compare your answer with the solution below

a. True