System transparency

Contents

System transparency¶

We will now focus on system transparency, i.e. the transparency of the system logic information. We aim to answer three questions:

What types of information fall under the category of system transparency.

Why different stakeholders can be interested in them.

How such information can be obtained and communicated.

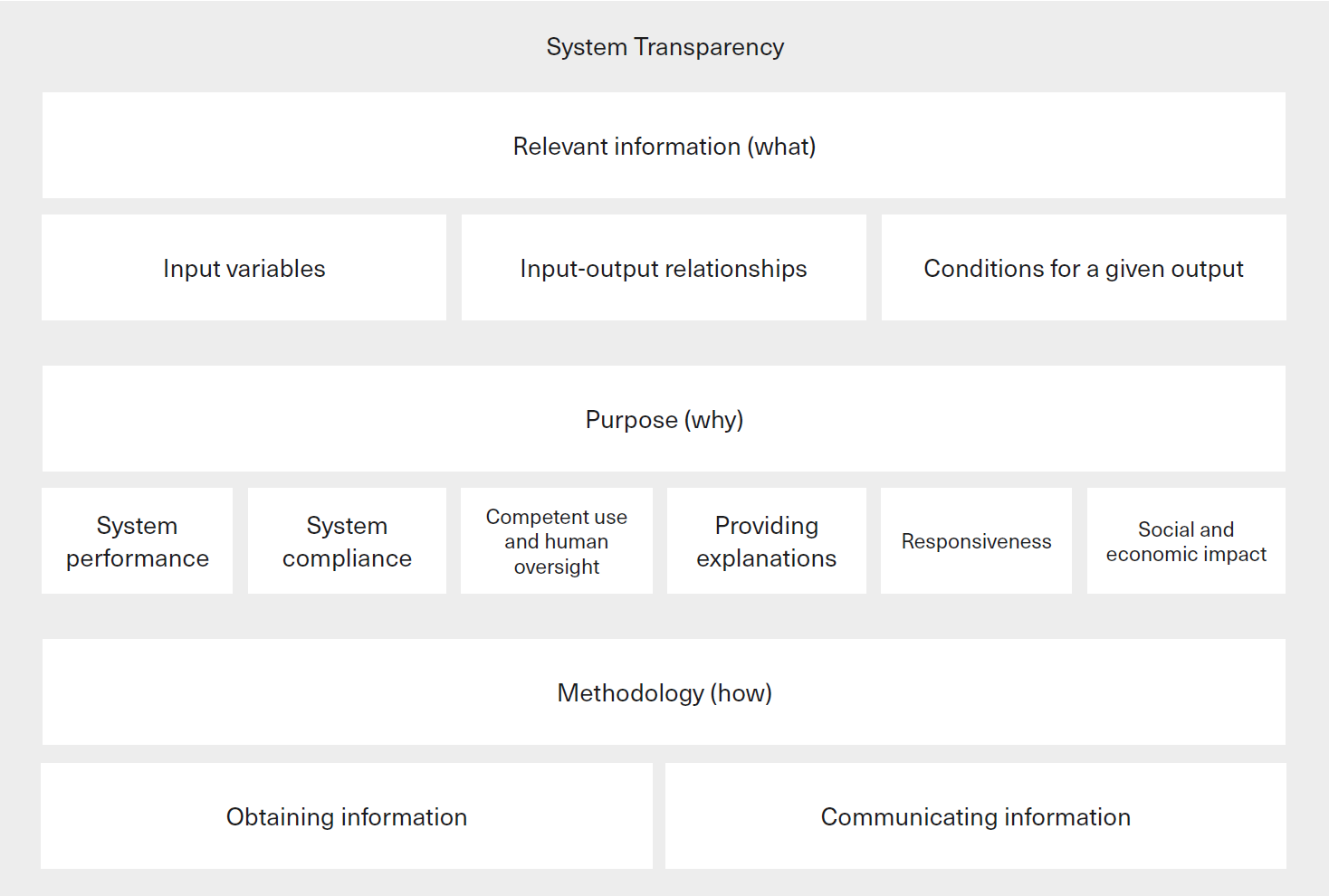

Figure Fig. 1 summarises system transparency in the three key questions above.

Fig. 1 The what, why, and how of system transparency [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

What relevant information?¶

System transparency refers to access to information about the operational logic of a system. The most transparent systems are simple systems where system logic information can be inferred purely from a system’s formal representation. Three types of information are considered relevant for system transparency:

(1) The input variables that a given system relies on: what are the types of information that the system uses in operation?

(2) The way in which the system transforms inputs into outputs: what is the relationship between input variables and system results?

(3) The conditions under which the system would produce a certain output: for what values of the input variables would the system return a specific value of interest?

Example

Let us know see illustrate how these three types of information can be inferred from the formal expression of a simple system below, a linear model calculates a person’s credit score \(y\) (the output variable) as a function of their weekly income \(x\) (the input variable):

This simple equation provides answers to all three questions outlined above:

the model relies on a single input variable, namely weekly income \(x\);

the model transforms the input variable into a credit score \(y\) (output) by multiplying it by a coefficient of 0.5 and adding a constant of 200;

in order for the model to yield an output value (credit score) of 600 (for example), the value of weekly income \(x\) would need to be £800.

Given that it is possible to infer these three types of information from its formal expression, this simple model is fully transparent. Since the input variable \(x\) is an easily understandable real-world property, this model is also full interpretable.

Many of the models that financial services firms use meet the definition of interpretable models. Their interpretation may require a higher level of mathematical knowledge, but their structure makes it possible to infer answers to the three questions above based on a formal model expression. The increases in model complexity enabled by ML methods can entail a decrease in or loss of model interpretability. It will generally be possible to identify the input variables that ML models rely on (information in category (1) above). Yet, model complexity can make it difficult to understand – from a formal expression of the model – how inputs are transformed into outputs (information in category (2)) or the conditions under which the model yields a specific output (information in category (3)).

Decreases in interpretability can take two forms. First, as model complexity increases, interpreting models requires greater technical skills. This possibility of opacity due to non-expertise shows that interpretability is a relative concept. Whether an ML system is considered interpretable can depend on the level of technical expertise of those trying to understand it. Second, model complexity can take forms that make ML systems inscrutable, affecting their interpretability regardless of expertise. In such cases, experts may still be able to give partial answers to the question of how the model transforms inputs into outputs from a formal representation of it – for example, by providing a high-level description of the model’s structure. Yet, these partial answers fall far short of the complete understanding that can be gained from the formal expression of the simple linear model above.

The lack of interpretability of certain types of models does not necessarily mean that adequate forms of system logic information are unobtainable for these ML systems. Instead of obtaining information from the formal expression of models, system logic information can also be obtained indirectly, by using auxiliary strategies and tools, such as explainability methods. However, these explainability methods cannot fully compensate for the information that can be obtained from interpretable systems.

Why such info?¶

Access to system logic information can serve to address relevant concerns (e.g. ensuring trustworthiness and responsible use) as well as to provide assurance about possible concerns (e.g. demonstrating trustworthiness and responsible use), as shown in.

Fig. 2 Areas of concern related to system transparency [Ostmann and Dorobantu, 2021] (maybe redraw later).¶

System performance¶

System logic information can be vital to understanding and improving the effectiveness, reliability, and robustness of ML systems. Where testing during system development reveals shortcomings, the analysis of input-output relationships can help identify possible improvements. Knowledge of input-output relationships can also be crucial when assessing the extent of possible performance issues that may arise during deployment. Stakeholders that may be interested in system logic information for these reasons include those involved in or making decisions about the development and use of ML systems as well as those seeking assurance about an ML system’s performance (including evaluation).

System compliance¶

Knowledge of the input variables that a system relies on and other aspects of system logic can be crucial to ensuring compliance with legal and regulatory standards and rules. For example, an understanding of system logic can be critical to avoiding unlawful discrimination; ensuring the adequacy in risk management; assessing the risks; or avoiding the unlawful processing of personal data. As in the case of system performance, stakeholders that may be interested in system logic information for these reasons include those involved in or making decisions about the development and use of ML systems as well as those seeking assurance about system compliance.

Competent use & human oversight¶

System users may need access to system logic information to ensure competent use. For example, knowledge of the input variables that a system relies on can be necessary to ensure that factors already accounted for in system outputs are not accounted for more than once (and therefore distort results) within a given decision process as a whole. Similarly, internal stakeholders in charge of oversight arrangements may need an understanding of system logic to determine what kind of oversight is required and to anticipate situations that call for intervention.

Providing explanations¶

System logic information can be at the core of explanations sought by decision recipients. For instance, it can provide assurance that decisions are taken in non-arbitrary and methodologically sound ways. In contexts such as credit or insurance underwriting, for example, access to system logic information can also be important in order for decision recipients to understand the effect that their behaviour may have on the decisions they receive.

Responsiveness¶

Customer service representatives, for example, may need to understand which input variables a system relies on, how the system transforms inputs into outputs, or under what conditions a system would yield certain results to be able to respond to customer queries.

How to obtain & communicate such info?¶

We now discuss how to obtain system logic information and how to communicate it to relevant stakeholders.

Obtaining system logic information¶

There are two methodological paths to obtaining information about an ML system’s input-output relationships and conditions under which it produces certain outputs:

Direct interpretation: Where complexity allows, relevant information can be obtained by analysing a formal representation of the system (as illustrated by the example of the simple linear model). This will be possible for many ML systems covered in this course, including those that are linear or nonlinear but have a relatively simple structure. However, it will not be possible for all ML systems, including those that are nonlinear and have a complex structure.

Indirect analysis using explainability methods: Various auxiliary methods can help shed light on system logic. Many of these methods are perturbation-based, including LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanation) [Ribeiro et al., 2016] and SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [Lundberg and Lee, 2017]. They rely on the analysis of changes in system outputs in response to changes in input values and can be used without access to a formal representation of the system. This is out of the scope of this course and hence will NOT be covered.

Communicating system logic information¶

System logic information is only useful if it is communicated to stakeholders in ways that are intelligible and meaningful.

Stakeholders differ in their familiarity with technical concepts. Depending on the audience, system logic information may need to be translated from technical into plain language to make it intelligible. The form and degree of translation required can vary between audiences. For example, while customers may seek information that is presented in non-technical language, senior managers may be more comfortable with technical terms. Non-textual forms of presenting system logic information, including visuals or interactive dashboards, can also enhance intelligibility. Whether information is meaningful depends on the questions that stakeholders seek to answer. Questions can differ significantly between stakeholders, as can the level of detail expected in the answer to each question.

This can be particularly relevant when comparing the transparency interests of customers with those involved in managing or monitoring the performance of ML systems. Three considerations are worth highlighting:

The role of counterfactuals: The interest of customers in accessing system logic information can often be driven by questions about the conditions under which a system would yield a certain output (eg a favourable decision outcome). Such counterfactual explanations differ from the types of information that are of interest to other stakeholders, eg those who want to understand system performance.

Relevance: Excessively detailed information or information that is irrelevant to customers’ queries can cause confusion and generate distrust.

Intuitiveness and simplicity: Customers may expect the logic of systems to be sufficiently intuitive and simple, so that they are able to remember it in day-to-day life and make informed choices about aspects of their behaviour that may affect decision outcomes. Intelligibility alone does not guarantee that these expectations are met.

Social and economic impact¶

System logic information can be essential to assessing potential social and economic impacts or providing assurance in relation to concerns about such impacts. For example, knowledge of the input variables used and the relationship between inputs and outputs can be relevant to understanding whether the system relies on inferences whose use may be considered ethically objectionable. Regulators, academics, or indeed wider civil society stakeholders may have an interest in system logic information in order to assess social and economic implications.