5 Enigma (optional)

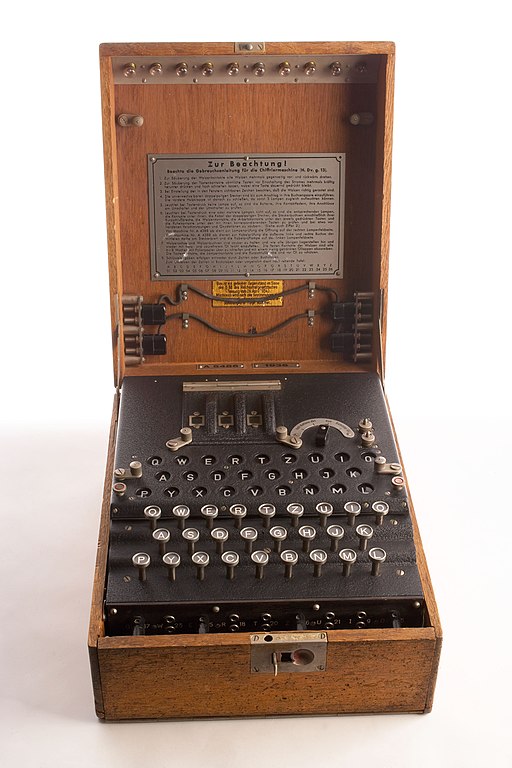

5.1 The Enigma cipher machine.

The Enigma machine was used by the German military during World War II to decode and encode secret communications. The simplest version of the machine consists of:

- A typewriter-style keyboard, which could be used to type out the message.

- A set of lamps, one for each letter of the alphabet. One of these lamps will light up every time a key on the keyboard is pressed.

- Three (or later four) rotors, chosen from a selection of five, each of which has 26 electrical contact pins on each side, and a different mapping of connections between them.

- An electrical reflector next to the left-hand rotor.

The choice of which rotors to use, in which slots, and their starting rotations, constitutes the encryption (and decryption) key.

When the machine is setup in the specified starting position, the user can press a key on the keyboard, and an electrical current will flow through the rotors from right-to-left, then through the reflector, then back through the rotors from left-to-right, and will cause a letter-lamp to light up. At least one of the rotors will then rotate by one step (the right-hand rotor rotates after every key press, the others less frequently), so that when the next key is pressed, the mappings from the keyboard to the lamps will be different.

Like Vigenère, Enigma is therefore a polyalphabetic substitution cipher: a given configuration of the machine is a mono-alphabetic substitution cipher, but we get a different configuration after every key press.

Since Enigma is a symmetric cipher, the procedures for encrypting a plaintext message and decrypting a ciphertext message are exactly the same: much like how you work the Vigenère square ‘in reverse’.

You can see a more visual explanation of the encryption and decryption process at Ada Computer Science.

Exercise: Have a go with the Enigma emulator. Some things to try:

- Set the starting rotors to something (e.g. “A,B,C”), then type out a short message. Note that after every keypress, the right hand rotor shifts by 1.

- After the end of that message, reset the rotors to the original position, and then type out the ciphertext that you got from the previous step. Hopefully you should now recover the original text.

- You can also try pressing the same key many times - what do you notice about the output ciphertext?

5.2 Cracking the Enigma

The reflector next to the rotors gives the Enigma the nice property that the settings for encryption and decryption are identical. However, it also gives rise to an important flaw (which you may have noticed from the exercise above): it is impossible for a letter to encrypt to itself.

This means that if you have a “crib” (i.e. a word or phrase that you are fairly sure will appear in the message), and you are trying out lots of possible keys, you can discard any where the same letter appears in the same position in the ciphertext and the proposed plaintext.

Using this, and various flaws in the procedures that Enigma operators used, Polish cryptographers were able to break Enigma in the 1930s. They then shared this knowledge with British and French cryptographers, and a cryptographic arms race ensued that lasted throughout World War II.

As extra layers of complexity were added to Enigma (a fourth rotor, a plug-board that mapped pairs of letters to one another, …), so the scale and complexity of the code-breaking efforts increased. An example of this is the development of the Bombe - an electro-mechanical device that could try all the 17576 (26×26×26) possible rotor positions in about 20 minutes.