6 Modular arithmetic I

To begin the second part of this challenge, we’ll take a brief look at modular arithmetic.\(\newcommand{\smod}[1]{\stackrel{\bmod #1}{\equiv\!\equiv}}\)

6.1 Congruences

Modular arithmetic is the same thing as regular arithmetic, but with one twist: we only care about the remainder when dividing by some number \(n\). Instead of talking about numbers, we talk about numbers modulo \(n\). For example,

\[5 \smod{3} 2\]

because both 5 and 2 have the same remainder when divided by \(3\).

In fact, the remainder when \(8\) is divided by \(3\) is also \(2\), so we can also say that:

\[5 \smod{3} 8\]

In mathematics, we say that two numbers are congruent modulo \(n\) if they have the same remainder when divided by \(n\). That is denoted here by the \(\equiv\) sign.

Exercise: Suppose that \(11 \stackrel{\bmod 5}{\equiv\!\equiv} x\). Can you list five possible (positive) values of \(x\)?

What can you say about all the values of \(x - 11\)?

More generally, if \(a \stackrel{\bmod n}{\equiv\!\equiv} b\), what can you say about \(a - b\)?

6.2 Working with modular arithmetic

Suppose that \(a \smod{n} p\) and \(b \smod{n} q\). Prove the following statements:

- \((a + b) \smod{n} (p + q)\).

- \((ab) \smod{n} (pq)\).

We will work through the first one. To do this proof, we need to use one key fact: if \(a \smod{n} p\), that means that there is some integer \(c\) for which \(a = p + cn\). In other words, \(a\) is some multiple of \(n\) plus \(p\).

If we do this separately for \(a\) and \(b\): \[\begin{align} a &= p + cn \\ b &= q + dn \end{align}\]

and then add these two together, we get:

\[\begin{align} a + b &= p + q + cn + dn \\ &= p + q + (c + d)n \end{align}\]

which means that \(a + b\) is some multiple of \(n\), plus \(p + q\). This is exactly the same as saying \((a + b) \smod{n} (p + q)\).

You can use the same strategy to prove statement (2).

Optional: If you have studied proof by induction, try using it to show that for all integers \(m > 0\), if \(a \smod{n} p\), then \((a^m) \smod{n} (p^m)\).

6.3 The modulo operator

Above, we have seen that if \(11 \smod{5} x\), then \(x\) can be \(1, 6, 11, 16, 21, \ldots\).

One of these values is special: it is \(1\), because that is the remainder itself when \(11\) is divided by \(5\).

To denote this special remainder, we write instead:

\[11 \bmod 5 = 1.\]

Even though \(11 \smod{5} 16\), it would not be correct to write \(11 \bmod 5 = 16\).

Exercise: If \(x \smod{n} y\), under what conditions can we say that \(x \bmod n = y\)?

You may find that this is more familiar to you than the congruence notation: for example, you may have used the mod function in a programming language, which performs this operation.

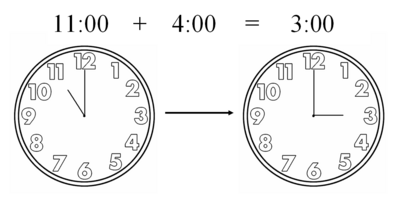

But also, many operations in daily life already involve this operator. When we tell the time we implicitly work in arithmetic modulo 12, which is why we know that 3 pm is 4 hours after 11 am.

can also be thought of as performing the same operation on clocks with a different number of hours to 12.

Question: Consider some other areas in life where we use modular arithmetic without thinking about it.

What day of the week will it be, five days from now?

If a room light is currently off and you flip the switch 7 times, will it be on or off?

Can you express these relations using modular arithmetic?

6.4 Calculator

To help you get a feel for modular arithmetic, here is a calculator that accepts (almost) any mathematical expression in the left-hand side. You can also specify a modulus, and the calculator will show you the result of the expression modulo that number. You may find this useful for the exercises below.

mod

6.5 Calculating remainders

Understanding the congruence operator, \(\smod{n}\), makes it far easier to perform some calculations.

For example, what is the remainder when \(33^{594}\) is divided by \(32\)? (Equally, what is \(33^{594} \bmod 32\)?)

We might first think about calculating \(33\) to the power of \(594\), and then dividing that by \(32\) to find the remainder. That sounds difficult: even a computer would struggle with such a large number! (Try using the calculator above, or Google’s built-in calculator, to calculate \(33^{594}\).)

But if we notice that \(33 \smod{32} 1\), then we can see that

\[\underbrace{33 \times 33 \times \cdots \times 33}_{\text{594 times}} \smod{32} \underbrace{1 \times 1 \cdots \times 1}_{\text{594 times}} \smod{32} 1,\]

because \(1\) to the power of anything is still \(1\).

Because \(1\) is smaller than \(32\), we can conclude that \(33^{594} \bmod 32 = 1\).

Challenge: If you did the proof by induction above, use that result to calculate the remainder when \(7^{175}\) is divided by \(16\).

If you did not do the proof by induction, or if you want a hint: try to find a pattern here: what is \(7^1 \bmod 16\)? and \(7^2 \bmod 16\)? and \(7^3 \bmod 16\)? Once you have found a pattern, think about why this might be the case.]