Co-Designing Trustworthy Assurance—Stakeholder Engagement¶

Chapter Overview

This section introduces and analyses the findings of several stakeholder engagement events, which were conducted to a) identify participant's attitudes towards DMHTs, b) understand which ethical values and principles they view as significant, and c) explore how to use this information to construct trustworthy assurance cases and argument patterns for relevant ethical goals.

First, we introduce the objectives, structure, and content of the workshops.

Second, we analyse the findings of our workshops, drawing connections with the methodology of trustworthy assurance. These findings support the development of two argument patterns, presented in chapter 5, which serve to distill recurring themes from all of workshop participants that were deemed significant.

Finally, we offer several recommendations for policy-makers, regulators, and developers, based on the preliminary results of the project.

Workshop Information¶

Participants¶

In the previous chapter we discussed our engagement with university students and administrators. This work was treated as a sub-project because of the specific focus on the HE sector as a limiting context. In this chapter we address workshops with a wider range of stakeholders and from a broader perspective. While the objectives remain the same across these two chapters, the findings and analysis in this section are representative of a wider range of concerns.1

The stakeholder groups we consider in this chapter are as follows:

- Policy-makers and regulators in healthcare

- Developers of DMHTs

- Researchers working in disciplines adjacent to digital mental healthcare

- Users with lived experience of DMHTs

Representatives from the first three stakeholder groups were invited to participate in a series of two workshops, the first of which laid the foundation for a subsequent participatory design workshop.

In contrast, users of DMHTs (4) were invited to a separate workshop (offered either online or in-person), which was organised with and facilitated by the McPin Foundation—a mental health research charity that provide advice and support on research strategies to involve participation and expertise from individuals with lived experience of mental health issues. This decision was made to ensure that participants were fully supported by experts throughout the workshops, and that our analysis of the findings was further supported by domain experts.

Methodology and Activities¶

Full details of our methodology and activities are provided in Appendix 1. Summary information is included in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1—summary information about the two sets out workshops.

| Workshop | Groups | Purpose of workshop | Main activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | Policy-makers and regulators, Developers, Researchers |

- To introduce participants to the methodology of trustworthy assurance - To identify key ethical values and principles that were salient or significant in the evaluation of digital mental healthcare | - Introductory presentations on a) the current landscape of digital mental healthcare, including representative harms and benefits, and b) the methodology and purpose of trustworthy assurance - Group discussion exploring the ethical values and principles associated with the design, development, and deployment of DMHTs, using case studies developed by our team |

| 1b | Policy-makers and regulators, Developers, Researchers |

- To explore a set of illustrative case studies that were designed to support the development of trustworthy assurance cases - To build trustworthy assurance cases using a prototype platform developed for this purpose | - A group discussion of the chosen case study (voted for by participants in the previous workshop) to ensure familiarity with the relevant details of the case study - A participatory design activity in which the participants collectively develop an assurance case for a specific ethical value or principle (e.g. health equity, explainable decisions) |

| 2 | Users of DMHTs (in-person; online) |

- To identify participants attitudes towards digital mental healthcare in general, and salient ethical issues more specifically. | - Exploratory discussion on the possible harms and benefits of digital mental healthcare. - Identification of key ethical values and principles. - Evaluation of sample claims made by a hypothetical team about actions or decisions undertaken during the design, development, and deployment of DMHTs. |

Analysis¶

Key Findings

- All groups emphasised fairness as a key ethical principle, but the specifics of how fairness was understood differed between groups.

- Additional emphasis was placed on ethical priorities that could be captured by either the accountability, explainability, or data SAFE-D principles (e.g. informed consent, transparency).

- Goals that are not directly coupled to any specific ethical principle2, such as clinical efficacy, were nevertheless significant topics for consideration among regulators and developers.

- Ensuring sufficient understanding of the trustworthy assurance methodology proved to be challenging in the time available. This was the case even with the participants who attended two workshops, where the first included preliminary material on the methodology.

As with the workshops described in the previous section, we conducted thematic analysis on the findings from the workshops, with the goal of addressing the objectives set out in the Introduction.3

In the following sections, we first discuss the specific themes for each set of workshops and then explore cross-cutting themes and differences, expanding on the Key Findings section above.

Workshops (1a and 1b) with policy-makers and regulators, developers, and researchers¶

Summary

- Nearly all of the ethical issues raised could be easily captured by the SAFE-D principles and their core attributes. However, additional space and emphasis is needed to capture the following concepts:

choice,patient choice,self-determination,autonomy. - Fairness was prioritised by the majority of participants. The principles was strongly linked to considerations such as

access to services,unequal distribution of health outcomes across demographic groups,bias in algorithmic decision-making, anddiverse and inclusive participation in service design. - Participants expressed positive sentiment towards the trustworthy assurance, noting its perceived value for processes such as transparent auditing, assessment, or procurement.

- Producing assurance cases was a challenging exercise for many, but there were no signs that these barriers could not be addressed with additional user guidance and familiarity.

Workshop 1a¶

The first workshop (1a) ensured that participants had sufficient information about the trustworthy assurance methodology, which was required for the second workshop. This information was provided while minimising the likelihood of priming the participants to evaluate our case studies with reference to specific ethical values or principles, such as the SAFE-D principles. Therefore, there were fewer findings from workshop 1a than with workshop 1b.

Note

Our goal was to identify which ethical principles mattered most to them, so we were careful not to highlight that we had already developed an existing framework (SAFE-D principles) that could unduly influence their feedback.

However, one relevant activity from workshop 1a that is worth mentioning was the explicit request to identify and discuss ethical values and principles that were seen as salient or significant in the context of the design, development, and deployment of trustworthy DMHTs.

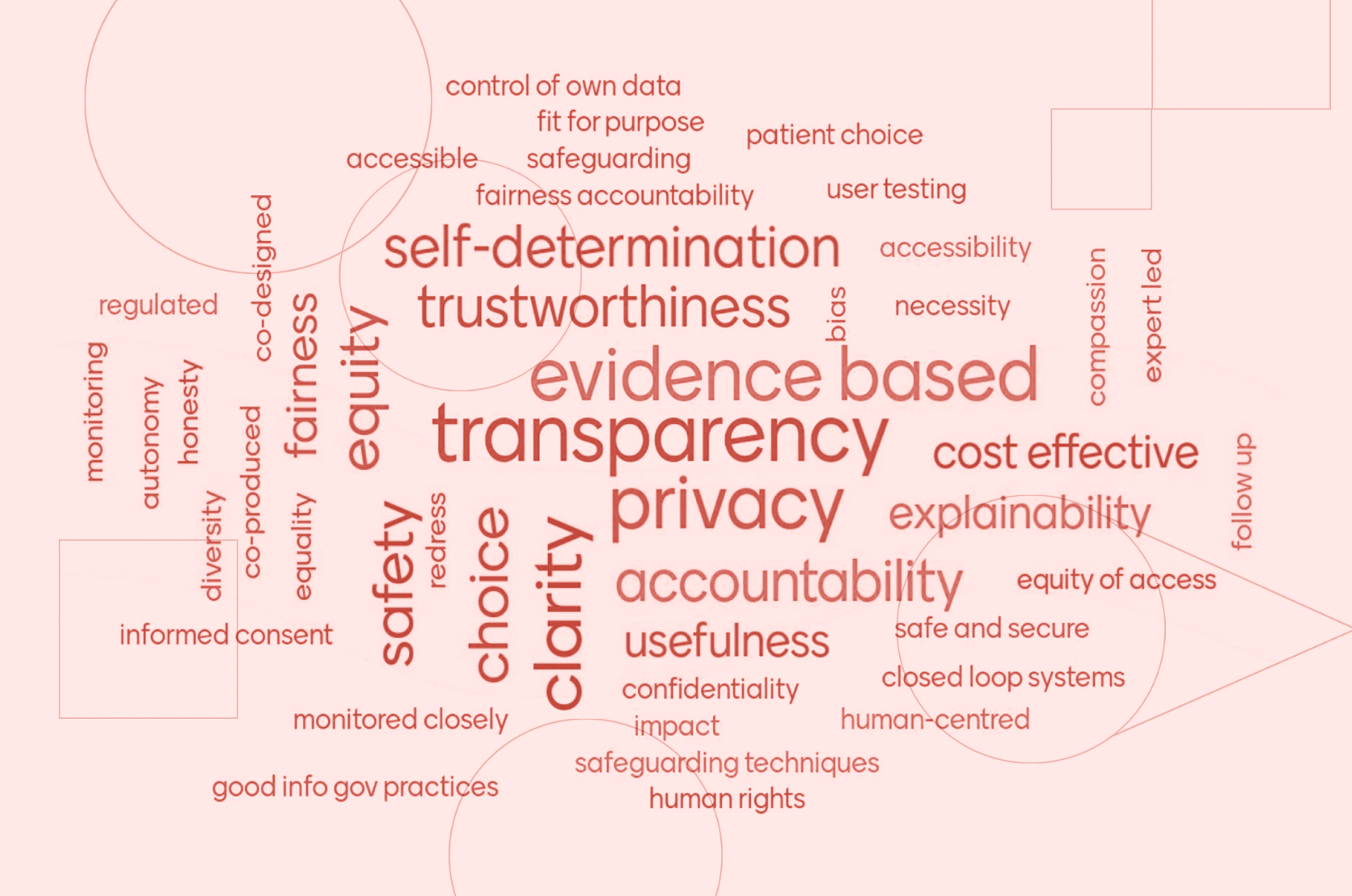

The following word cloud shows participant answers for the question,

Question

'What values and principles matter to you?'

Figure 4.1: a word cloud displaying answers to the question, 'What values and principles matter to you?'

Immediately, it can be seen that transparency, privacy, and evidence-based were clearly significant for our participants. And related concepts, such as accountability, explainability, and clarity are also salient.

However, there is also a wide variety of terms here, and many are either synonymous or closely related. For instance, self-determination, autonomy, informed consent, control of own data, and patient choice could be clustered together. And so could equity, fairness, equality, and equity of access.

Although intended as an exploratory and preliminary activity, the findings represent a useful source of contextual information that can help illuminate some of the themes that emerged during the workshop discussion and activities. For instance, the vast majority of the concepts map onto our existing framework, and overlap with the SAFE-D principles and corresponding attributes (see Table 3.2)4.

Table 4.2—mapping the word cloud concepts onto the SAFE-D principles.

| Principle | Concept |

|---|---|

| Sustainability | evidence-based, fit for purpose, safeguarding, monitoring, cost effective, follow up, redress, safety, usefulness, impact |

| Accountability | transparency, safeguarding, accountability, expert led, regulated, monitoring, honesty, redress, monitored closely |

| Fairness | accessible/accessibility, fairness, co-designed, compassion, bias, equity, co-produced, diversity, equality, equality of access |

| Explainability | transparency, evidence-based, clarity, accessible, honesty explainability, monitored closely |

| Data Quality, Integrity, Privacy and Protection | privacy, control of own data, regulated, honesty, usefulness, safe and secure, confidentiality |

Two considerations can be extracted from this mapping:

- The SAFE-D principles provide an informative starting point for ethical reflection and deliberation in digital mental healthcare, as they do in other domains, and would likely serve as useful normative goals for trustworthy assurance cases.

- There are gaps and nuances in the framework when applied to digital mental healthcare that need to be addressed.

In terms of the second consideration, there are a few clarifications that need to be made.

Firstly, the main gap relates to the ability for the principles to capture concepts such as,choice, patient choice, self-determination, and autonomy. The appearance of these concepts is not surprising. Patient autonomy, informed consent, and participatory decision-making in healthcare are longstanding ethical values, and are reflected in well-known bioethical principles.5

In the original domain-general setting in which the SAFE-D principles were designed, informed consent and autonomous decision-making were captured under principles such as fairness and explainability (e.g. ensuring that information about an algorithmic decision is accessible and explainable to users). However, as we will see shortly, there are nuances in the design, development, and deployment of DMHTs that put pressure on the choice of subsuming these values into another principle.

Secondly, there are other principles, such as human-centred, human rights, honesty and closed loop systems that are either ambiguous or do not fit cleanly into the existing framework. In the context of the first two, this is simply because they stand outside of the SAFE-D principles as meta-frameworks (e.g. human rights law). For instance, the SAFE-D principles have been put forward as a means for safeguarding human rights6. However, in the case of honesty and closed loop systems, there was simply insufficient information during discussion to determine whether these are merely outliers or express an existing attribute that fits within the framework.

Fortunately, the activities and discussion from the second workshop help emphasise more salient topics that were deemed significant by the stakeholders.

Workshop 1b¶

The second workshop (1b) focused on a participatory design activity that was created to evaluate the trustworthy assurance methodology and attempt to operationalise some of the ethical principles explored in the first workshop.

For the main activity, participants were asked to review and discuss the ethical issues related to a specific case study and then develop a hypothetical assurance case that communicated how a set of decisions or actions had been undertaken to justify the ethical goals and properties that they had discussed. The groups were free to choose the goal. And the case study, which had also been selected by participants, involved the use of a decision support system that offered tailored and real-time recommendations to a psychiatrist during consultation with a patient (e.g. during assessment)(see Appendix 1).

Two breakout groups were formed and the (incomplete) assurance cases are depicted below.

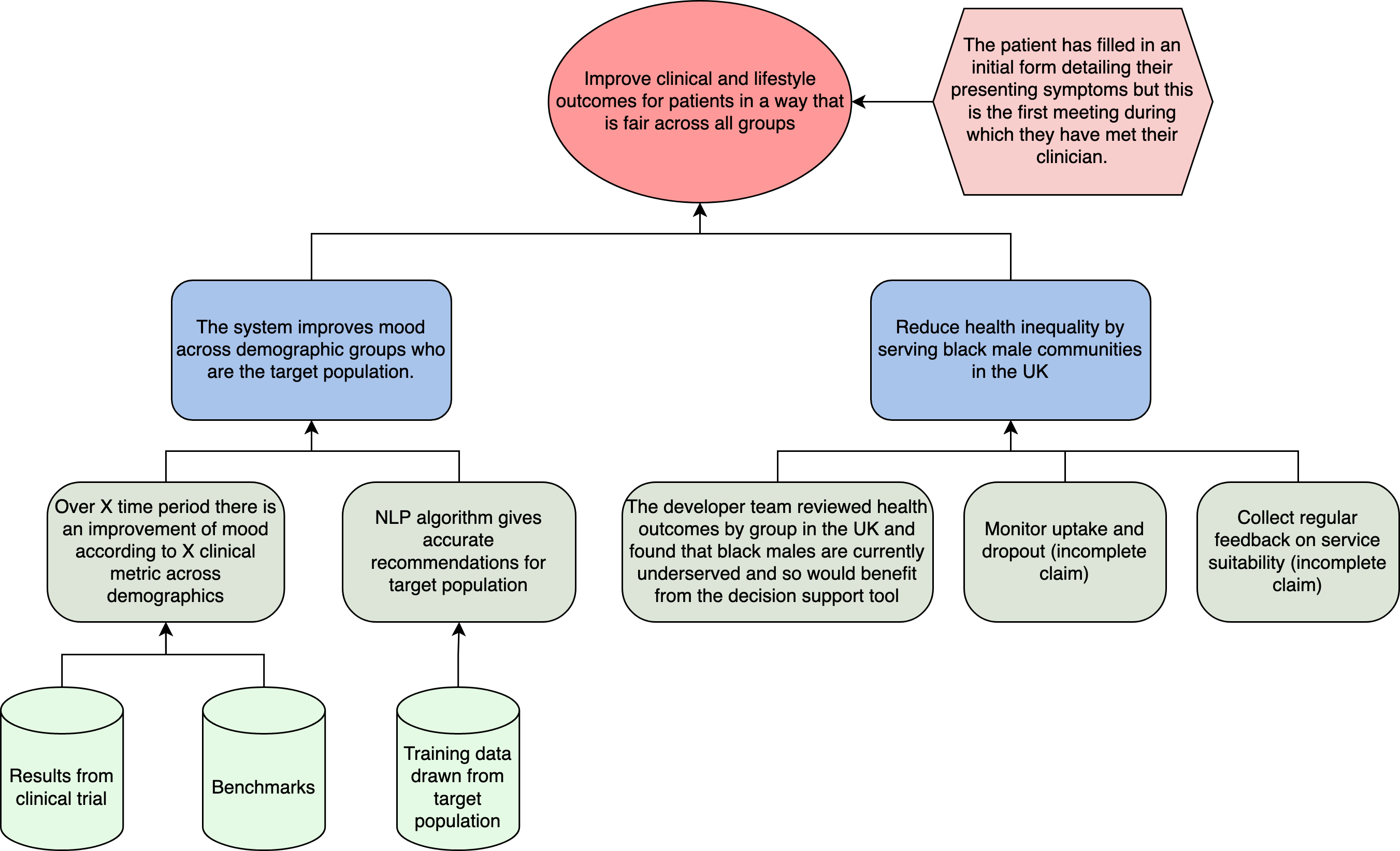

Figure 4.2: the assurance case for breakout group 1, focusing on ensuring fair outcomes for patients.

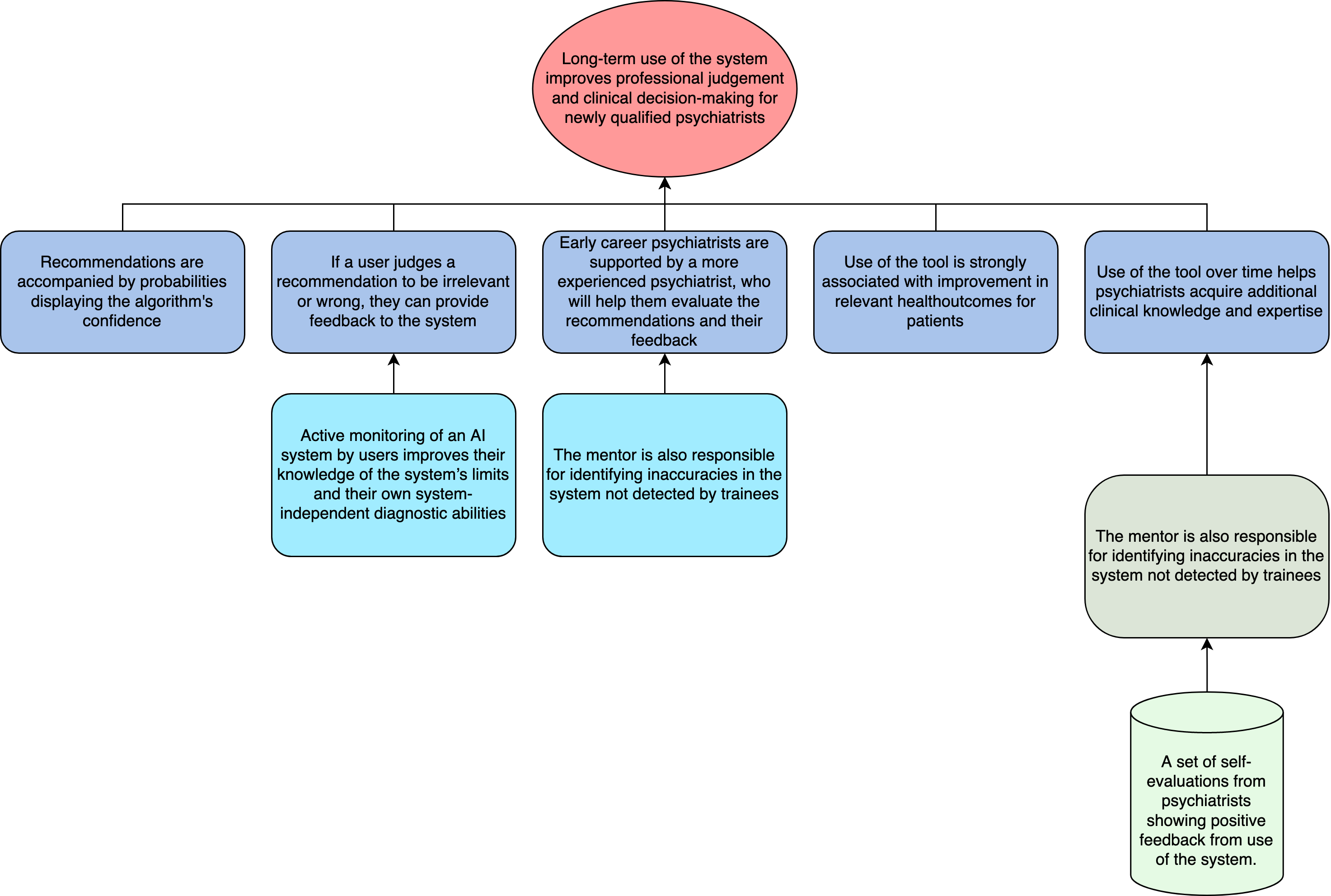

Figure 4.3: the assurance case for breakout group 2, focusing on supporting the professional judgement of psychiatrists.

As noted above, fairness was a significant focus for the participants, and so it is unsurprising that one of the groups chose to explore an assurance case related to this goal.

The assurance cases are incomplete because a lot of time was spent in discussion. However, some of the statements made during discussion can help elucidate aspects of the case. For instance, the choice to emphasise a group that is underserved, was linked to aforementioned components of fairness such as unequal access:

"There are clearly real benefits for many people being able to access digital technology but there are also many people who won't be able to access it. Prior to even thinking about the introduction of digital technology in mental health services, we were aware of very longstanding inequalities in access to an outcomes from mental health services. There's a fear, particularly during COVID and lockdown and the move to "digital by default" that some of those divisions will grow larger as a result."

Interestingly, the second breakout group chose to focus on the impact of the hypothetical decision support system upon the healthcare professionals.7

As the image above shows, their goal was framed in terms of supporting the "professional judgement" of the psychiatrist. On its own, this goal would be underspecified, making it difficult to accurately link to any of the SAFE-D principles or core attributes. Fortunately, the discussion and property claims of the assurance case help clarify the intentions of this group, but some residual ambiguity remains due to the inclusion of two core themes:

- The long-term effects of the system on professional development and judgement

- The responsibility of early career psychiatrists, who may be less able to challenge or contest automated recommendations.

These two themes emerged from discussion about the potential harmful impact of the system on the judgement of psychiatrists, such as the possibility of automation bias (i.e. the tendency for users to be unduly influenced by automated decision-making, even when their own judgement would be preferable or more accurate). For instance, when the group considered which forms of evidence they would expect to see included to provide assurance that this risk had been managed and mitigated, they added an evidential claim and artefact that communicated additional mentor support (from a senior healthcare professional) and positive self-evaluation from the user (see right of Figure 4.3).

The inclusion of this segment in the assurance case cannot be divorced from consideration about the responsibility that a user has for their own decisions, as well as the institutional mechanisms of accountability that ought to be put in place to support users of decision support systems. Therefore, it remains unclear whether the goal of this assurance case could be captured by a single SAFE-D principle. On the one hand, Sustainability would be a good candidate for capturing the long-term impacts of the system on user autonomy and professional judgement. On the other hand, Accountability would be preferable for those attributes concerned with responsible decision-making and institutional accountability. These questions were not raised with the participants, nor is there sufficient information to infer their intentions.

However, the following quotation from one of the (developer) participants is illuminating for the challenges involved in ensuring responsible decision-making in situations where multiple organisations are involved in a distributed project lifecycle:

"Ultimately, once you hand over the software and you set them [procuring organisation] up, how they actually use it and why they've got it can be a bit of a mystery. Sometimes, organisations are looking for ways to support people but they don't have much resource and they think digital might be a good way of doing that. So, maybe it's still a good motivation but there's also this expectation that digital can do a lot more than it can, and it's a cheap way of ticking a box."

In general, it was challenging to develop a full assurance case for several reasons:

- Time limits imposed by workshop

- Lack of familiarity with the Trustworthy Assurance methodology

- Challenges of reconciling broad range of perspectives to co-create a shared goal and common understanding

The first two barriers would be easy to reconcile. For instance, although we dedicated a significant portion of time to introducing and exploring the trustworthy assurance methodology, more hands-on experience with the tool could have helped the participatory activity of developing an assurance case for the hypothetical case studies.

The third barrier, however, is harder to overcome. In our initial project planning meetings we considered running separate workshops for all of the stakeholder groups, but settled on mixed engagement events because of the perceived benefit of facilitating communication between different group—a key benefit of the methodology itself. A portion of this barrier could be resolved with additional time, but the value-based and translational gap that typically exists between different groups (e.g. regulators and developers) will remain. Therefore, the following recommendation is proposed as a measure to address this challenge:

Readiness, skills, and training should be prioritised both within organisations (e.g. how to implement ethical considerations into the project lifecycle) and across organisations (e.g. how to develop and adopt best practices). In addition, common capacity building should be supported by regulators and industry representatives (e.g. shared risk mapping, regulatory gap analysis, and horizon scanning activities to help create and maintain a common pool of expertise).8

Feedback¶

Following the participatory activity, participants were asked to complete an anonymous survey, which was designed to elicit additional information about the perceived value of the trustworthy assurance methodology. Therefore, despite the small sample, it is worth analysing the responses before we turn to the final workshop with users of DMHTs.

Question 1

To what extent do you agree/disagree with the following statement: "The methodology of trustworthy assurance would be helpful in identifying potential ethical risks which arise while designing, developing and deploying a DMHT".

| Option | # Responses |

|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | 4 |

| Agree | 9 |

| Undecided | 2 |

| Disagree | 0 |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 |

This initial feedback is positive. The majority of respondents 'agree' or 'strongly agree' with the statement, indicating support for the methodology despite the challenges faced during the activity.

Unfortunately, the sample size is too small to infer anything meaningful about the distribution of participants across these categories. For instance, whether developers were more positive than regulators or vice versa. 9

Question 2

To what extent do you agree/disagree with the following statement: "The methodology of trustworthy assurance would be a helpful means through which to communicate to other stakeholders that a DMHT is trustworthy".

Similarly, the majority of respondents 'agree' or 'strongly agree' with the above statement, reinforcing our prior assumption about the communicative value of trustworthy assurance. However, as we will see shortly, there are some future areas for improvement, which likely explain the increased number of 'undecided' responses, which were primarily from policy-makers. 10

| Option | # Responses |

|---|---|

| Strongly Agree | 4 |

| Agree | 8 |

| Undecided | 3 |

| Disagree | 0 |

| Strongly Disagree | 0 |

Question 3

What do you consider to be the primary advantages of the ethical assurance methodology?

The feedback from this question can be summarised as follows:

- The primary advantage is having a capacity to support a structured and end-to-end approach to project governance, facilitated by shared aims and objectives for broader normative goals (e.g. health equity).

For instance, as one participant noted,

- "Its [i.e. trustworthy assurance] emphasis on structure and evidence supporting claims which derive from an overarching goal. It really helps to be forced to think in these terms to keep an open mind about what requirements a certain system has at different stages of design, development and deployment. I love how flexible the system is, so that it can account for many technologies and contexts on the market." [Researcher]

Although trustworthy assurance is a structured process, as this participant emphasises, flexibility is also maintained by enabling myriad goals, properties, and evidence to be selected to fit the context of a specific project. Where this flexibility is used to facilitate bidirectional decision-making about project aims and objectives, trustworthy assurance can (as another participant notes) support the development of

- "A level playing field expectation from procurers, and a common improvement in practice." [Developer]

And, in turn,

- "will help developers, commissioners and service providers to know that equality/ethics has been considered." [Policy-maker]

Question 4

What do you consider to be the primary disadvantages of the ethical assurance methodology? Please specify any aspects of the methodology which you believe require further refinement.

While it is encouraging to see many positive responses, it is also important to consider critical feedback, as it is here that potential gaps and barriers can be addressed. The first critical comment attenuates the positive feedback about the methodology's flexibility noted above:

- "The open-ended nature of the methodology makes it difficult to know what to include in scope and may pose a difficulty for comparing assurance cases between manufacturers, for instance." [Developer]

This is a valid concern, but can be addressed through the use of a) argument patterns and b) guidance about how ethical principles can be operationalised throughout the project lifecycle (see below and chapter 5).

The second point relates to organisational culture and readiness, and the challenge of considering competing incentive or disincentive structures—a theme also raised in the previous chapter:

- "There are lots of examples of people producing equality impact assessments11 that are little more than a tickbox exercise. It's important they are produced, but it's even more important they are of a high quality." [Policy-maker]

We have previously emphasised that trustworthy assurance should not be reduced to a mere checklist or compliance exercise. The model of the project lifecycle is one means for mitigating the risk of misuse in this manner, as it emphasises the iterative and dynamic process of building an assurance case over the course of the entire project lifecycle. As such, the act of building an assurance case is not rendered a checklist exercise that is carried out at the end of a project as an afterthought, but is rather approached as subject to ongoing review.

However, this prescription is going to be in conflict with alternative interests, as one participant notes:

- "Assurance may be not in the interest of profit" [Researcher]

At present, our methodology is not supported by a theory of change for how organisations can adopt the methodology into their own practices. One possibility would be to work with public sector organisations and regulators to establish a requirement for those responding to tenders to provide an assurance case for a relevant ethical goal (e.g. non-discrimination, explainability). Alternatively, we could investigate how specific goals in the context of healthcare could expand upon existing regulations (e.g. medical device approval).

The following three questions were posed to the respective participants as a means of eliciting more specific feedback about perceived obstacles to the successful adoption and integration of trustworthy assurance into their respective practices.

Question 5a

As a developer, are there any objections or external obstacles which would prevent you from producing an ethical assurance case during the design, development and deployment of a new DMHT?

The first two comments relate to a similar concern about organisational readiness and incentive/disincentive structures raised above:

- "External obstacles are business needs and drivers that might cut down on the time needed to use a methodology like this properly. It can be hard to create and argue for time to give ethics proper consideration when there are business deadlines."

- "To produce an ethical assurance case would require additional effort. It would ideally be integrated into other early design processes alongside clinical safety case, data protection impact assessment, etc. The process would need to be usable in an (agile) product development context, where an ethical assurance case would be updated as changes are made to the tool in an iterative fashion."

Here, our analysis and response echoes some of the comments made earlier (e.g. conflict with profit incentives). However, one additional comment can be made: having tailored versions of the project lifecycle model, which reflect the unique needs and challenges of specific domains, would help developers identify which actions could be undertaken (and when) to meet the goal of an assurance case. This development would, furthermore, create space for the development of supporting standards, as acknowledge by the following participant:

- "Clarity on expected standards would be the largest obstacle. We noticed the biggest upswing in GDPR policy uptake came when we started offering standard starter policies."

Question 5b

As a researcher working on DMHTs, do you see any obstacles to the uptake of ethical assurance in the sector?

The responses from researchers were mostly positive in the sense that few obstacles were identified. However, there was a skepticism about the likelihood of the private sector adopting the practices of trustworthy assurance.

- "Ethical regulation, in the private sector, is non-existent. Theories around mental health, in general, are too underdeveloped, the digital context and the methods to use for research unexplored, non-rigorous, and misaligned with gold standards. Ethical assurance has no tangible rewards for a designer with a purpose or aim, independently of the positive principles used to design the system."

We can, again, note that targeting procurement practices in the public sector may be a positive first step, and, moreover, that complementarity with existing regulation could increase adoption. This latter point was highlighted by the responses from the policy-makers.

Question 5c

As a policy-maker, do you consider the methodology of ethical assurance to be compatible with existing regulatory mechanisms in the sector? Please describe any obstacles to the adoption of ethical assurance in the digital mental healthcare sector.

- "I'd recommend that you align to existing regs where possible (e.g. goals could be 'conform to GDPR' or 'meet regulatory requirements' rather than more abstract items) and make it easy for non-experts to use."

The response from another policy-maker, however, suggests that caution should still be exercised when seeking alignment, in order to avoid confusion:

- "It [trustworthy assurance] is compatible but it may overlap considerably with other requirements eg. ESF, DTAC etc. creating confusion and overload for developers."

The final section of the survey, asked participants to offer any remaining feedback. Here, the selection of responses serves as a useful summary on the above analysis.

First, our analysis shows that while many recognise the value of the methodology, significant obstacles remain in the successful adoption of trustworthy assurance. Most notably, the friction presented by antagonistic incentive/disincentive structures. While our comments suggest possible avenues that may counteract some of the disincentives, a comment raised by one participant suggests that more work needs to be done to better communicate the positive value of using trustworthy assurance:

- "How do we ensure developers of mental health tools use or are even aware of these types of methodologies? What is the incentive to use these methodologies?" [Developer]

We outlined many of the potential benefits of trustworthy assurance in the first section, but ensuring others are convinced of these values will take time. In alignment with the final two comments from our participants, a means for reducing the friction would be to build out additional case studies or examples of best practice, which can help serve as a point of orientation for other developers and organisations.

- "The worked example made things easier to understand and think about." [Developer]

- "Having a best practice example to learn from and emulate would help our practice." [Developer]

This suggestion is a variation of the recommendation above about supporting readiness, skills and training, and common capacity building. However, in the next chapter we will build on this by setting out a clearer proposal and recommendation for the incorporation of argument patterns.

Workshops with users of DMHTs¶

Summary

The workshops with users exposed wide-ranging, nuanced, and interconnected attitudes, while contributing to practical and complementary recommendations for developers and regulators.

Four central themes emerged from the workshops:

- Distrust as a barrier to accessing and using DMHTs

- Stakeholder and user engagement as a means for ensuring accountability

- Explainable technology and systems as a pre-requisite for informed choice

- Ensuring fairness by reducing digital exclusion, bias, and discrimination, and promoting social justice

While all of the themes are interconnected, the fourth theme especially is inseparable from the others.

Overview¶

The workshops with users of DMHTs were co-organised and facilitated by the McPin foundation—a mental health research charity. This ensured an additional level of support from those with domain expertise, in addition to the participants' lived experience, and helped reduce interpreter bias in our analysis.

We held two workshops (one in person and one online) to improve accessibility for participants (e.g. reducing geographic restrictions, supporting those who were uncomfortable/unable to attend in-person to still participate). The information that participants received and the activities that were carried out were identical across the workshops, except for the medium in which the activities were conducted (e.g. use of a collaborative whiteboard in the online setting).

There were two activities that participants contributed to. Both were designed to maximise the ability of the feedback to shape and inform the design of our methodology and recommendations while minimising the need for prior reading (e.g. information about argument-based assurance). A talk preceded each of the activities to ensure that participants were equipped to contribute in a meaningful way.

- Activity 1: participants were asked to reflect on a range of possible use cases for DMHTs and evaluate possible harms and benefits by answering the following questions:

- Which ethical values or principles matter to you in the context of digital mental healthcare?

- What are some positive use cases for DMHTs?

- What are some negative use cases for DMHTs?

- Activity 2: participants were given a set of claims made by a fictional development team about one of the four case studies, and asked to evaluate the claim based on the following criteria:

- Whether the claim appeared to be motivated by or support an ethical value or principle.

- Whether they found the claim reassuring or whether it raised concerns.

- What evidence, if any, they would expect to see to support or validate the claim.

In both activities, participants were encouraged to explore tangential points in dialogue with the group. The purpose of these activities was to provide a general scaffold for discussion, from which salient and significant themes could be identified with the participants. Therefore, in our analysis we do not differentiate between the findings from the two activities, but instead group them together and make specific recommendations linked to the relevant themes.

However, one output from the first activity can be presented as a stand-alone output. Table 4.3 presents a summary of the positive and negative uses of DMHTs, as judged by the workshop participants. Although this feedback is incorporated into our own thematic analysis, the reader may find it illuminating to consider the responses prior to reviewing our subsequent analysis.

Table 4.3—participant's perceptions about the positive and negative uses of DMHTs.

| Positive Use Cases | Negative Use Cases |

|---|---|

| Useful for opening dialogue with clinicians | Predatory "targeted marketing", business/finance models that take advantage of people, using people’s data to attain information and target them. Manufactured empathy is not empathy. |

| Tools for self-management and self-help | Limitations of the technology leading to problems. Difficulty in determining when there is an emergency, not understanding tone of voice. |

| Useful for remaining anonymous | Selling people’s personal data |

| Could be useful for preserving continuity of care, and personalisation of care | Privacy issues (young people especially) |

| Useful for dangerous or violent person where clinical contact is bad/not recommended | Stalking, coercive control and abuse, people pretending to be identities that they are not. |

| Potential for a deeper understanding of mental health difficulties due to the amount of data that could be collected | Infiltration in creepy ways into personal/sex life. |

| Accessibility - can do in your own time and from your own home. Useful for those who live remote areas where travel is not possible or expensive | Constant monitoring by the device, increased paranoia, over-reliance on device. |

| Reducing the load on psychiatrists | Increased loneliness. Social isolation can be exacerbated when you are talking to a chatbot, or you can become reliant on the chatbot. |

| Ability to share recovery (or other mental health) narratives digitally | Misrepresentation of outcomes. When usage time is monitored, not using the device can indicate deep depression or apathy but could also indicate that there are other good things going on in the real world they are engaged with. |

| Tech use and being online has been problematic for some service users and giving it all up has been a good factor in their recovery | |

| Some people don't all have access to privacy to use digital technologies in their own home. | |

| Need to keep up-to-date hardware to access may impact those on lower incomes and increase the electronic waste problem. |

Thematic Analysis¶

The following themes were identified across the two workshops and activities. They have been co-developed by the users, the facilitators from the McPin foundation, and ourselves.

Distrust as a barrier to access and use¶

There were high levels of distrust and skepticism within the group regarding the societal and individual benefits of digital mental health. However, the sources and targets of the distrust or skepticism were nuanced and wide-ranging.

Several participants, for example, were keen to acknowledge that the issues with digital technologies should be set against the backdrop of the current issues facing mental health services (e.g. long wait lists, insufficient funding). This includes a recognition of the difficulty of getting face-to-face appointments and the biases of human healthcare professionals:

“I didn’t like it [online CBT], I was just desperate to have any form of counselling and because the waiting list was two years, I thought it was better than nothing.

“You get people in the NHS who are as bad as chatbots. They may as well be robots.”

Some participants linked this distrust to cultural attitudes they held:

"My parents are [information redacted] and really value privacy and that is why I didn’t use a smartphone for a long time. And a lot of my friends who are African or Caribbean or Asian don’t have a smartphone because of privacy.”

Whereas others linked the source of distrust to potential conflicts of interest:

"Who is the advocate for the technology? Is it the psychiatrist pushing it because it makes their life easier?"

"Who holds the purse strings?"

For some participants, the distrust or skepticism was directed towards specific technologies such as chatbots:

“[Chatbots are] good for customer service, but sometimes it feels like they are being used to replace humans”

“How is it ethical to develop a solution like that, and allow these technologies to exist on the marketplace when they are doing more harm than good?”

But, again, the skepticism that participants held was typically nuanced and voiced with caveats:

"I am very comfortable with tech. There are some circumstances where I trust technology more than people. I trust an iPad food ordering system than a human.”

In some instances, such as AI-assisted surgery, involvement of technology should optimise for safety. But in mental healthcare, human interaction and involvement will always be vital to a trustworthy and supportive relationship.

From these preliminary remarks, it is important to remember how we disentangled the concepts of 'trust' and 'trustworthiness' back in Chapter 1. To recall, 'trust' can refer to a belief or attitude that is directed towards an object, person, or proposition (among other things), whereas 'trustworthiness' refers to the perceived property or attribute which an individual uses to determine whether to place trust (e.g. whether to trust a news article based on its quoted sources). Differentiating these terms is helpful for evaluating whether there are reasonable (and unreasonable) grounds for placing trust. For example, a person may have reasonable grounds for their distrust in an organisation, where the organisation has a history of violating data protection and privacy laws. In contrast, another person may have unreasonable grounds for their skepticism about the clinical efficacy of a technology based on an accessible, well-validated, and reliable evidence base.

Identifying the reasons for why users may trust or distrust a DMHT can help organisations assess and evaluate both the trustworthiness of their teams and services, and identify opportunities for intervention. Phrased as a recommendation:

Recommendation

Organisations should consider both the trustworthiness of their products and services, but also the reasons why users may trust or distrust them.

Acting upon this recommendation requires organisations to engage stakeholders, which links to the next theme that emerged during discussion.

Accountability through engagement¶

In her BBC Reith Lectures, 'A Question of Trust', moral philosopher Onora O’Neill argues that, "we need more intelligent forms of accountability, and that we need to focus less on grandiose ideals of transparency and rather more on limiting deception."12

O'Neill's prescription captures many of the concerns and aspirations of the participants. For instance, several participants voiced concerns with the deceptive practices of some organisations to exploit vulnerable users through social media marketing (e.g. adolescents). Other participants viewed the over-reliance on privacy policies to be an instance of deceptive practice, as such policies rarely provide sufficient information to address a user's concern, such as data use:

"people should know how data is being used, who has access to it."

In contrast, participants were keen to express their desire for genuine forms of accountability and responsibility exercised through the life cycle of a DMHT, achieved through meaningful engagement and participation of stakeholders. The slogan, "nothing about us without us" comes to mind here13. And, there are also close ties between this theme and the subsequent one (i.e. explainability):

"No transparency without accountability and explainability"

This emphasis on engagement and meaningful forms of participation will be returned to, as it was a recurring and cross-cutting theme. However, several practical recommendations can be offered here in connection with the theme of accountability:

Recommendations

- Accountability should be built into all stages of the project lifecycle, and requires both stakeholder engagement and also diversity within the project team (especially neurodiversity).

- Where there is a risk of harm to users, organisations should be transparent about how these risks were identified (e.g. who was involved in the risk assessment), how they were mitigated, and what mechanisms for redress are available to impacted individuals.

Explainability as a pre-requisite for informed choice¶

As has already been noted, there was a strong dislike and distrust towards the perceived over-reliance on privacy policies. As several participants noted:

"The culture of small-print is pervasive, but the culture of consent is not built into a business model”

“it is not consent because you are not informed”

"Pooled permissions are a risk to privacy and there should be more modular options to accept or deny the Terms and Conditions. Usually, you must ‘accept all’ for an app to work."

However, the following question from one participant inverts the perspective and shifts focus onto the user:

“How do we communicate our privacy policy”

Traditional frameworks in biomedical ethics link informed consent to values such as patient autonomy. In short, without sufficient knowledge about how a service operates or the risks associated with a medical intervention, a patient has little to no meaningful choice about whether to engage or accept a recommendation from a healthcare professional.

The above quotation is a succinct and cogent way of capturing the ethical importance of these values. But its emphasis on a more active form of communication goes beyond the practical goal of informed and autonomous decision-making, and reiterates the importance of stakeholder participation as a form of meaningful input and influence.

To understand why this shift in framing matters, consider the fact that for many users there may be no practical choice about whether to engage if there is only a single option available to them. This may be because of long wait times, limited provision of services, or perhaps because a user is only choosing to engage at a point of crisis.

“I didn’t like it [online CBT], I was just desperate to have any form of counselling and because the waiting list was two years, I thought it was better than nothing. It will keep me from having suicidal ideation.”

Capturing these themes and building on the previous sections recommendations, we can add the following recommendation.

Recommendation

Information that is necessary to and supportive of informed choice should not be hidden within obscure privacy policies; it should be made accessible to users as explanations of how a system was designed, developed, and deployed. In doing so, organisations should be clear about how they define and operationalise key terms, such as 'mental health' or 'well-being' and how their understanding of the terms may have impacted the design, development, and evaluation of a service.

But the shift from choice to active involvement is not just about improving explanations to support participation, it is also about improving access more generally. As one participant acknowledges, this is fundamentally a matter of fairness.

"if everything is moving towards digital, who is going to be excluded. Is it going to be harder to access face-to-face care".

This brings us to our final theme.

Fairness: reducing digital exclusion, bias and discrimination, and promoting social justice¶

Despite being left until the end of the chapter, this final theme stood out as one of the most significant and resonates with many aspects of the themes above and also with the other workshops.

In a similar manner to the other workshops, the plurality of concepts referenced in this theme's heading reflects the breadth, nuance, and interconnectedness of the ideas that were raised. For instance, the participants' understanding of what we call 'fairness' in the SAFE-D principle framework was nuanced and multifaceted. Although we are unable to capture all of the comments raised, the topics discussed touched upon centuries-old forms of sociocultural and structural discrimination or oppression, historical abuses of vulnerable groups by scientific research groups and institutions, epistemic injustices, and power imbalances that disproportionately affect marginalised communities.

Digging deeper into some of these topics, concerns about the negative impacts of digital exclusion and the widening digital divide, exacerbated by growing socioeconomic inequalities, were highlighted frequently. Some participants linked their concerns to gaps in current regulation and legislation:

"Ensuring inclusion and accessibility requires going beyond protected characteristics: disability & class and access to technology."14

While others emphasised structural forms of exclusion in technology design:

"When designing based on AI and machine learning, we look at what works for the mass and the smaller minority communities and the rare types of people/personality are excluded by design."

Similarly, some participants raised questions about the possibility of algorithmic discrimination due to varying levels of efficacy across demographic groups:

"How will it [the hypothetical NLP algorithm in one of our case studies] account for regional words and dialect? Slang terms? Cultural terms? Accessibility in different languages."

These critical comments and considerations should not be isolated from the remarks outlined in previous themes or the following recommendations raised by participants:

- Distrust as a barrier to access and use: historic forms of oppression, injustice, and discrimination partially explain why some individuals and groups have low levels of trust towards these technologies and the organisations that design, develop, and deploy them.

- Accountability through engagement: the risks of harm and the likely benefits associated with DMHTs may not be shared equally by all groups. Inclusive stakeholder engagement is one mechanism by which oversight and accountability in the risk management process can be achieved. To paraphrase one participant, 'those on a design team should be a diverse, invested group, and diversity should not be tokenistic'.

- Explainability as a pre-requisite for informed choice: as a bioethical principle, ensuring informed consent is often linked to the ethical value of self-determination. The significance of the principle is understood by many to arise from a universal right to autonomous decision-making in matters relating to one's health and well-being. While the domain of mental healthcare places restrictions on this right when it conflicts with other duties (e.g. protecting others from harm), these are limiting cases for which there are existing norms and guidelines in place15. In general, ensuring that an individual has sufficient access to the explanations needed about how a technology operates, in order to make an informed choice about whether to use the technology, has already been acknowledged as a vital ethical goal. However, there are many barriers in place to achieving this goal, and where they disproportionately affect certain groups (e.g. those with low levels of digital literacy or access to support services) this goal connects with the related goal of promoting social justice.

Improving health equity is already a key priority across many organisations in the UK.16 However, the longstanding impacts and challenges of COVID-19 are still affecting society, often in a disproportionate and unjust manner, and many lessons still need to be learned and adopted, as highlighted in 'Build Back Fairer: The Covid-19 Marmot Review', from the Institute of Health Equity and Health Foundation.

Unlike the other themes, we do not offer any specific recommendations on this topic beyond the reiteration of the importance of stakeholder engagement and meaningful participation. This is partially because there is already a wealth of extant research produced by organisations across the public and third sectors offer evidence-based policy recommendations. However, it is also because we pick up on this theme directly in the next chapter and present an argument pattern to help promote the goal of fairness in digital mental health.

-

There is, of course, a trade-off here between the narrower and wider perspectives, which we discuss in Appendix 1. ↩

-

This is not to say that clinical efficacy is not a key component of ethical decision-making. For instance, the bioethical principle of beneficence clearly requires sufficient levels of clinical efficacy. ↩

-

These objectives were as follows: 1) To explore whether and how the methodology of argument-based assurance could be extended to address ethical issues in the context of digital mental healthcare. 2) To evaluate how an extension of the methodology could support stakeholder co-design and engagement, in order to build a more trustworthy and responsible ecosystem of digital mental healthcare. 3) To lay the theoretical and practical foundations for scaling the ethical assurance methodology to new domains, while integrating wider regulatory guidance (e.g., technical standards). ↩

-

The attentive reader will see significant overlap between the concepts that are mapped onto the principles, and subsequently the principles themselves (e.g. explainability and accountability). Because the principles were not designed to be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive, this overlap is to be expected. ↩

-

Beauchamp, T. L., & Childress, J. F. (2013). Principles of biomedical ethics (7th ed.). Oxford University Press. ↩

-

Leslie, D. et al. (2022). Human rights, democracy, and the rule of law assurance framework for AI systems: A proposal. Accessed: https://rm.coe.int/huderaf-coe-final-1-2752-6741-5300-v-1/1680a3f688 ↩

-

Our case studies included a section on 'Affected individuals, groups, and other stakeholders'. For this case study, 'psychiatrists' were included (see case study 3. ↩

-

See our report on developing 'Common Regulatory Capacity for AI' for more on these topics. ↩

-

For transparency, the distribution of responses by stakeholder group is as follows: Strongly agree: policy-maker x2, researcher x1, developer x1; Agree: policy-maker x1, researcher x4, developer x2; Undecided: policy-maker x2 ↩

-

Again, these results should be treated with caution due to the small sample size. Strongly agree: policy-maker x1, researcher x1, developer x2; Agree: policy-maker x2, researcher x4, developer x4; Undecided: policy-maker x2, developer x1 ↩

-

See Equality and Human Rights Commission. (2014, August 1). Technical Guidance on the Public Sector Equality Duty: England | Equality and Human Rights Commission. Technical Guidance on the Public Sector Equality Duty: England. https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/publication-download/technical-guidance-public-sector-equality-duty-england ↩

-

O’Neill, O. (2002). A Question of Trust. Cambridge University Press, pp. 77–78. ↩

-

Charlton, J. I. (1998). Nothing about us without us: Disability Oppression and Empowerment. University of California Press. ↩

-

This theme is built into an argument pattern in the next chapter. The pattern urges reflection upon and consideration of deep patterns of discrimination, marginalisation, and minoritisation, which can exacerbate mental health issues, but which fall beyond protected characteristics that lie outside the scope of the Equality Act 2010 (e.g. poverty, housing, employment). ↩

-

On these points it is worth noting that the Mental Health Act, which sets out the legislation that is used to determine when it is appropriate to place restrictions on people, has been subject to proposed reform in recent months. Readers may find the "new guiding principles" of particular interest in the context of this report (see here). ↩

-

For instance, the goal of increasing health equality is incorporated into a recent discussion paper from the Department of Health and Social Care's Mental health and wellbeing plan, the 'Advancing mental health equalities' strategy from NHS England, the Welsh Government's 'Together for Mental Health' delivery plan, and an ongoing consideration for the Scottish Government following the publication of an equality impact assessment of their mental health strategy back in 2017. ↩