Defining Responsible Research and Innovation¶

A Definition of Responsible of Research and Innovation¶

While this module does not advocate for a single definition of 'responsible research and innovation', the following definition is a good starting point for understanding the term:

Responsible Research and Innovation is a transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view on the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society). - Rene Von Schomberg1

Let's break this definition down.

First, we have the following phrase:

"transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other".

This is straightforward enough. Without transparency and interaction between innovators, researchers, and society, the outcomes or consequences of research and innovation cannot be meaningfully scrutinised or challenged, and possible harms or unintended consequences may go unnoticed.

Illustrative example

For example, if a medical research team failed to interact with and explain to their study participants the risks of a novel drug they are testing, the lack of transparency may prevent the participants from giving their meaningful and informed consent to the possible risks involved with their participation.

Second, we have the goal to which the transparent, interactive process is directed:

"with a view on the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process".

A process of responsible research and innovation should be dialogical and inclusive to make space for the unavoidable plurality of values that are implicated within the research and innovation lifecycle.

For instance, many would agree that technological advances in renewable energy are desirable because of their contribution to the creation of a more sustainable future. However, there may be disagreement about the specifics of a particular project, such as the development of a hydroelectric power plant that displaces downstream communities by disrupting the local ecology. Such a tension is one between competing values and interests, which can only be observed and resolved through a transparent and interactive process with affected and impacted stakeholders.2

Finally, von Schomberg's definition draws our attention to how RRI facilitates a

"proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society".

This is another way of saying that scientific research and technological innovation do not operate in a vacuum. This part of the definition draws our attention to the fact that the practices and processes or research and innovation occur at a specific place and time, and also to an awareness of their consequences, which can vary in scope and impact. That is, they are "embedded" in society.

Some obvious examples of research and innovation with wide-reaching impacts include the development of the atomic bomb, the discovery of penicillin, or the invention of the internet. But all research and innovation has the potential to reshape societal practices and social norms or expectations in unexpected ways.

A less obviously important example

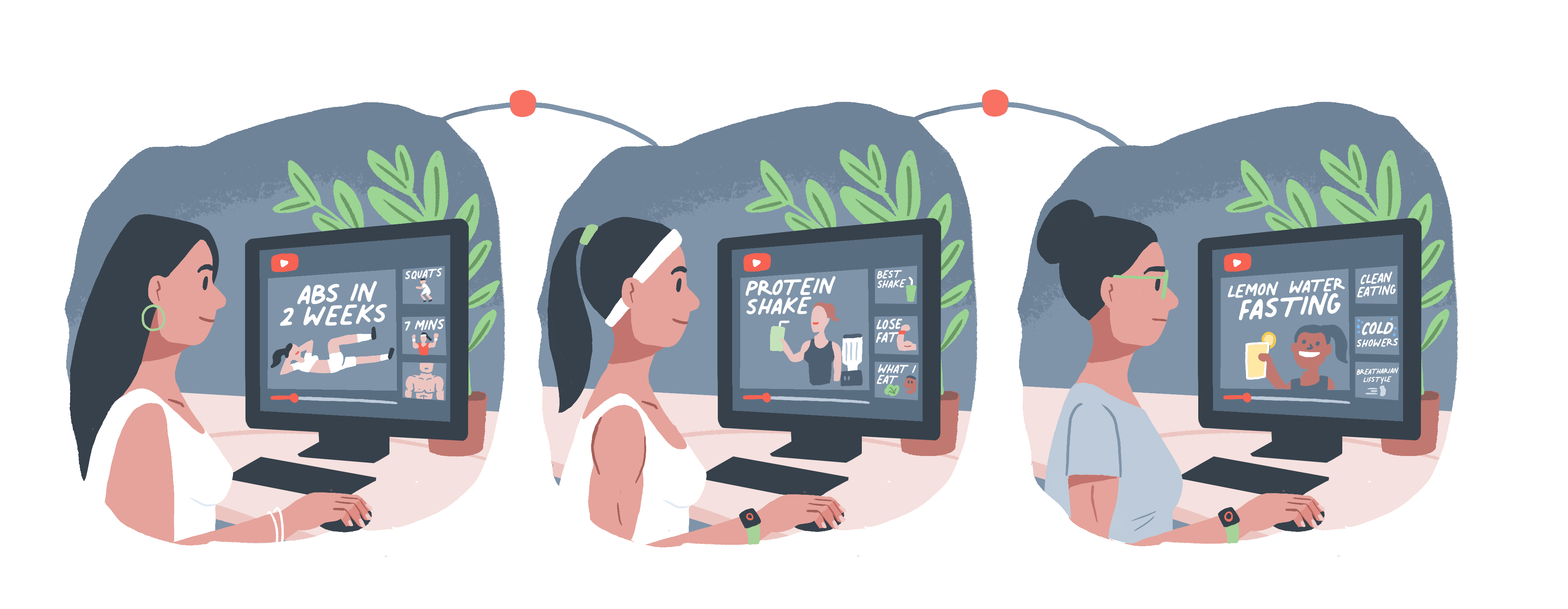

An example of this is the recommendation algorithm used by YouTube. The algorithm optimises for engagement, i.e. how long people watch the videos recommended to them, and therefore recommends videos deemed most-likely to keep users engaged in the platform for the maximum of time possible. At first flance, the high-reaching implications of this might not be obvious. But as has become increasingly clear over the last few years, YouTube recommendations quickly steer people into conspiracy theories, misinformation, or unhealthy information. From flat-earth conspiracy theories to extreme diets and pro-anorexia videos, YouTube recommendation systems seem drive users towards extreme content at a much higher rate that search algorithms do.3

RRI takes this inextricable relationship between science, technology, and society as its starting point, taking seriously the moral duties and obligations that such a relationship inculcates.

An (Incomplete) History of the term 'Responsible Research and Innovation'¶

The term 'responsible research and innovation' is strongly associated with the European Commission's Framework Programmes for Research and Technological Development—a set of funding programmes that support research in the European Union.

Beginning with the seventh framework programme in 2010, and continuing on through Horizon 2020 (FP8), the term 'responsible research and innovation' became increasingly important for the European Commission's policy.

Since the European Commission's initiative, other national funding bodies have also shown a commitment to RRI. For example, in the United Kingdom, the UKRI's Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council have developed the AREA framework, which sets out four principles for RRI: Anticipate, Reflect, Engage, and Act (AREA).

The AREA Framework¶

The AREA framework is a principles-based framework. That is, the framework comprises four principles that serve to operationalise the term 'responsible research and innovation', while also providing high-level guidance on practical decision-making.

Operationalise

The term 'operationalise' (or, operationalisation), in the context of principles, means to further refine or specify the principle in actionable or measurable terms so that it can be implemented and evaluated in practice (e.g. during a project). This typically involves creating a set of rules, procedures, or guidelines for how the principle should be applied in a particular context.

For example, in a data science project involving sensitive information, the principle 'protect user data and safeguard privacy' (summarised as 'data privacy') may be operationalised through adherence to the following procedures:

- Identify what data is considered sensitive and requires extra protection

- Obtain explicit consent from individuals before collecting or using their sensitive data

- Regularly review and update the data protection measures in place

- Provide individuals with the means to access, correct or delete their personal data

- Establish procedures for reporting and investigating any data breaches

- Provide training to employees on data protection and privacy practices.

This list could be extended as required by the specific context of the project.

While different from the definitional approach discussed previously, the four principles of the AREA framework have a lot in common with Von Schomberg's definition. Let's take a look at each of them.

Anticipate¶

Describe and analyse the impacts, intended or otherwise, that might arise. Do not seek to predict but rather support the exploration of possible impacts (such as economic, social and environmental) and implications that may otherwise remain uncovered and little discussed. Here we can see the following values and commitments (among others) being expressed or alluded to:

- Importance of the interlocking values of 'transparency' and 'understanding' emphasised through the requirement to 'describe and analyse' impacts in a creative and exploratory manner (e.g. through inclusive dialogue with stakeholders)

- The significance of anticipatory deliberation at the start of a project, to avoid issues such as technological lock-in or technical debt.4

- The recognition that "predicting" all possible harms or opportunities is unlikely, and that procedures should be established to ensure future harms caused can be suitably remediated.

Reflect¶

Reflect on the purposes of, motivations for and potential implications of the research, together with the associated uncertainties, areas of ignorance, assumptions, framings, questions, dilemmas and social transformations these may bring. Here we can see the following values and commitments (among others) being expressed or alluded to:

- The need to clearly identify the underlying (and sometimes competing) values behind a project (e.g. improving patient welfare, generating profit for shareholders)

- Epistemic humility about what is known and what is uncertain, and a commitment to communicating this uncertainty clearly to stakeholders and affected people.

Engage¶

Open up such visions, impacts and questioning to broader deliberation, dialogue, engagement and debate in an inclusive way. Here we can see the following values and commitments (among others) being expressed or alluded to:

- The importance of ensuring diverse groups have a meaningful opportunity to participate in these reflections. And, where the project is likely to affect a group of marginalised or vulnerable individuals, that priority is given to ensuring they are empowered to contribute to discussion around dilemmas, transformations, etc.

- The value of multi-disciplinary collaboration to enhance and widen the scope of possible futures that are envisioned (e.g. how large language models, such as Chat-GPT could continue to alter and shape societal practices).

Act¶

Use these processes to influence the direction and trajectory of the research and innovation process itself. The final principle draws upon and synthesises the previous principles to embody and enact an ethical approach to responsible action in research and innovation projects.

This principle, while less substantive than the previous, should also be understood as a process-based commitment. That is, responsible action is unlikely to be characterised by a one-off decision or action. Rather, it requires consideration of how the various, interlocking actions across a project's lifecycle come together to create a form of collective responsibility, as was discussed in the previous section.

CARE & ACT

A similar set of principles, called CARE & ACT principles, were developed by Ethics and Responsible Innovation team at the Turing.

If you would like to know more about them, you can go to our course on AI Ethics and Governance.

Note: An updated version of the AI Ethics and Governance skills track is coming soon!.

Ethics as Compliance¶

One pitfall to be mindful of is treating the principles of RRI as a form of compliance. This perspective reduces a vital and significant process to a mindless tick-box exercise. As Leonelli argues:

"A case in point is that of clinical trials, where top-down effort to provide general guidelines for best practice that has undoubtedly led to real and substantial improvements in overall compliance with the underlying ethical principles over the last two decades—and yet has also made ethical compliance into a ‘tick-box’ exercise, which researchers often view as a drag on their research time, and which has provided an excuse to delegate away any potential concerns with the ethical implications of research work." (Leonelli, 2016)5

This is why anticipation, reflection, and engagement come before action and not at the end of a project to satisfy some pre-existing and external criteria. It is also why our 'project lifecycle model'—introduced in the next module—seeks to embed and operationalise ethical principles throughout a project's lifecycle. In doing so, the requirement of responsible action is not external to the day-to-day research and innovation activities, but embedded within a project's activities. Acting in a responsible manner, therefore, means remaining attentive to the contextual risks and opportunities posed throughout a research or innovation project.

Science, Technology, and Society¶

This summary of 'responsible research and innovation' barely scratches the surface of the relevant literature.6 However, it is sufficient for present purposes to draw attention to two motivating drivers behind the majority of approaches and framework:

- RRI requires a critical awareness of and reflection on the impact that science and technology can have on society

- RRI involves the appreciation of and continuous commitment to the meaningful participation of members of the public in a dialogue about how science and technology should shape society.

In a later set of modules, we will introduce a new set of principles—the SAFE-D principles—that have been specifically designed to meet the unique needs and challenges of responsible research and innovation in data science and AI. As such, we will not use any of the previous definitions or frameworks. However, it is worth knowing about them to be able to appreciate how our own framework is both influenced by and builds upon complementary approaches.

-

Von Schomberg, R. (2011). Towards responsible research and innovation in the information and communication technologies and security technologies fields. Publications Office of the European Union. ↩

-

Our skills track on

'Public Engagement of Data Science and AI'goes into more detail about these topics. Note: An updated version of the Public Engagement of Data Science and AI skills track is coming soon! ↩ -

You can read more on how this happens in this blogpost by Guillaume Chaslot, one of the computer scientists who helped build YouTube's recommendation algorithm, and play around with the open-source YouTube recommendation explorer he built. ↩

-

'Lock-in' refers to the situation where early (and foundational) design choices made about, say, the use of a specific software architecture, can lead to a situation where it becomes very challenging to alter the behaviour or function of a system without massive upheaval and expense. The related term 'technical debt' refers to the cost of the additional rework caused by choosing an easy solution now instead of a better approach that would take longer but avoid the lock-in. ↩

-

Leonelli, S. (2016). Locating ethics in data science: Responsibility and accountability in global and distributed knowledge production systems. Philosophical transactions of the Royal society A: Mathematical, physical and engineering sciences, 374(2083). ↩

-

More information can be found in our

further resources section. Note: Our further resources section is coming soon! ↩