The Scope and Horizon of Responsibility¶

The Boundaries of Responsibility¶

Consider the following scenario.

A research team have developed a predictive model, which is well-validated in a particular context (e.g. for diagnosing an illness in a well-defined cohort of patients; for predicting house prices in a specific locale). They publish their data (withholding any sensitive information), details of their methods, and their model, in accordance with some widely agreed upon protocol or set of practices (e.g. for reproducible, replicable, and open science). They also carefully set out the limitations of their model in a journal article, including the limits of their model's generalisability that apply without further re-training and validation. Finally, they include a permissive license on reuse of their model, but set out specific restrictions for a list of "non-permitted" uses of their model, determined based on their own risk assessment activities.

Now, consider the following questions:

What is the team responsible for?

- Are the team responsible for any harms caused by a company who try to commercialise their model by embedding it into a novel system that falls under one of the teams "non-permitted" uses?

- Are the team responsible for any harms caused by another research team who deploy the original model in a new context but fail to carry out any of the suggested re-training and validation of the model in the new context (e.g. with updated and representative data)?

- Are the team responsible for any data leaks from their model that arise because of the methods they chose to use when training the model?1

- Are the team responsible for the accidental publication of sensitive data, which occurs as a result of human error when one of their teams uploads the project repository online for the purpose of reproducibility and replicability?

These questions all pertain to the scope or limit of the team's responsibility. Although individual answers to these questions may vary, they are likely to follow this trend:

What is the team responsible for?

- Team very unlikely to be deemed responsible

- Team unlikely to be deemed responsible

- Team may be deemed responsible

- Team likely to be deemed responsible

In the first case, it is quite obvious that the company are using the model in ways that the original team had taken steps to prevent (i.e. license restrictions on reuse). And, in the second case, the project team had also set out careful limitations on their model by following well-established protocols.

But, the third case is where we transition into a gray area.

Whether you believe the project team to be responsible, whether fully or partially, for the leakage in the third case will depend on several factors. For example, in this third case the issue seems to arise from a design choice made during model training, which could have occurred because of a lack of knowledge within the team about the vulnerabilities of certain training methods. Given the fast-changing nature of data science and AI, knowledge of vulnerabilities such as a model leakage can remain unknown to many teams, especially those with fewer resources and capacity. How sympathetic you are to the challenge of keeping abreast of this fast-paced field will undoubtedly influence your decision about how and whether to attribute responsibility.

But, in the fourth case, many are likely to ascribe responsibility to one or more members of the team. For instance, perhaps the project manager should have had greater oversight of the team's data management practices and implemented adequate training? Maybe there should have been safeguards to prevent accidents such as this one from ever happening (e.g. secure research environments that prevent egress of sensitive data)? Or, perhaps the individual who uploaded the sensitive data should have just been paying closer attention and was fully responsible!?

The specific answer you give does not matter here. What is important is to acknowledge that the demands of responsibility have boundaries that are often vaguely drawn. Our attempts to reduce this vagueness and better delineate these boundaries requires careful reflection and inclusive deliberation.

In the following sections we will explore these boundaries further.

Ought Implies Can

A widely agreed upon moral standard, attributable to the philosopher Immanuel Kant, which is relevant here is the precept, "Ought Implies Can". In short, you are only morally responsible or obligated to perform some action if you are capable of doing so.

For example, you would not be responsible for saving a dying person if you lacked the required medical training needed to save them. And, to flip this example on its head, you would be acting irresponsibly if you tried, say, to carry out surgery on someone without having undergone the necessary surgical training, no matter how beneficial your intentions.

Rules and principles such as 'ought implies can' also serve to set boundaries on our moral duties, responsibilities, and obligations.

To whom are we responsible?¶

Let's start with a thought experiment from the moral philosopher, Peter Singer, which addresses the spatial (or geographic) dimension of moral responsibility.2 Consider the following scenario.

On your way to work each day you walk along a river. One morning, you spot a child that has fallen in and appears to be drowning. However, saving the child would result in you ruining your clothes and being late to work.

Singer asks, 'do you have any obligation to jump in and rescue the child?'

When asked this question, almost all of us would answer with a resounding "yes", except where there are overriding factors (e.g. being unable to swim yourself—another example of the 'ought implies can' precept).

Singer continues, 'does the cost of your clothes affect your decision, or would it make a difference that there are other people walking past the pond who would equally be able to rescue the child but are not doing so?'

Again, most of us would say, 'no, the cost of clothes should not be valued beyond the life of a child, and it does not matter that others are not acting as they ought to do'. Another strike against the diffusion of responsibility.

And then we come to the crux of the thought experiment: what if the child were far away in another country, and although they are no longer drowning, we could save their life at virtually no cost to ourselves? If proximity or distance make no difference to our moral consideration, as Singer would indeed argue, then as he explains,

'we are all in that situation of the person passing the shallow pond: we can all save lives of people, both children and adults, who would otherwise die, and we can do so at a very small cost to us'

Whether for the cost of a coffee, a mobile app, or another subscription service, global aid charities can help us save the lives of those in need. Although many of us do not donate to global aid charities, this fact is separate from whether we ought to.

Singer is arguing in this famous thought experiment that when asking ourselves 'to whom are we responsible?', geographical considerations should not (at least in principle) play a part in our answer. That is, Singer argues physical proximity should play no role in determining our duties to help others (as long as one can indeed help someone remotely).

While not as forceful as the above thought experiment, many projects involving data-driven technologies give rise to similar challenges about the scope of our moral obligations. For example, the following scenarios all emphasise salient factors related to our capacity for moral concern and the effect of spatial separation:

- A data analyst who is physically separated from the subjects in her dataset, viewing them merely as numerical representations on a screen, may be less likely to extend them the same moral consideration for privacy or informed consent as a scientist gathering data during an in-person experiment.

- A software engineer developing a biometric identity system for a national agency may be unable to fully appreciate the impact that such a system will have on people from poorer backgrounds who have lower levels of digital literacy or access to technology.

- A climate scientist deciding where to place environmental monitoring systems to record pollution levels may be unable to access demographic information that would reveal how their choices, which are guided only by considerations of maximising coverage, nevertheless fail to monitor neighbourhoods that are overwhelmingly populated by minority groups. As a result, the benefits of their systems accrue to already affluent areas simply because of the ability to detect, say, air pollution more accurately in the areas where the sensors are located.

Understanding the impact that data-driven technologies can have on society, especially those with international scope (e.g. social media platforms), requires us to consider individuals and communities beyond our immediate sphere of concern. And, in doing so, we often find ourselves drawing an implicit boundary around those we consider and those we do not.

Drawing Boundaries

This section will not attempt to provide any general guidance on drawing boundaries in practice—beyond the simple precepts such as 'ought implies can'. To do so without first considering the context-specific factors of a particular project would either a) take us too far afield into moral philosophy, or b) simply cause confusion and tangential discussion points. It is sufficient for our purpose to just draw attention to the issue.

Our skills track on AI Ethics and Governance, however, goes into more detail on relevant topics.

Note: An updated version of the AI Ethics and Governance skills track is coming soon!.

Responsibility for Future Generations¶

We have explored the spatial dimension of our sphere of moral concern, but what about the temporal dimension?

Question

How far into the future should or does our responsibility extend?

One way to think about this question, popular among decision theorists, is to adopt a function that represents your level of responsibility as dependant on time and increasing uncertainty. For instance, you may think that because it is increasingly difficult to be certain of the consequences of your actions as time increases (recall the AREA framework), responsibility should therefore decline in a way that is proportional to the increase in uncertainty. But what is the shape or properties of such a function?

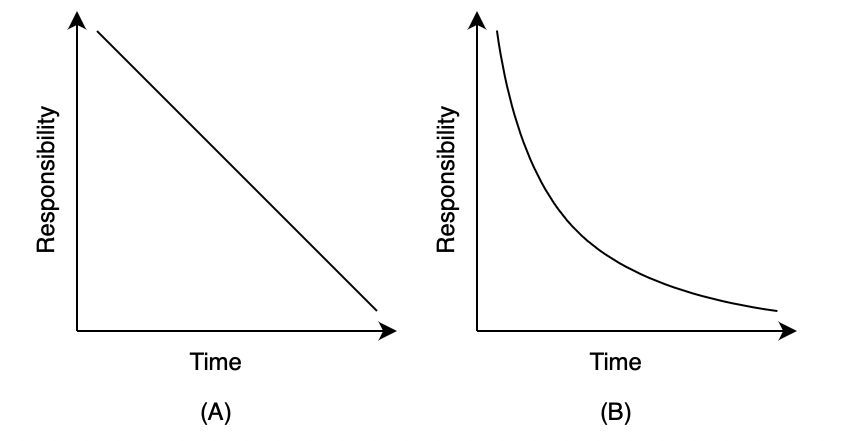

Two possible options include the functions shown in graph A, which represents your level of responsibility as a function that decreases linearly over time, and graph B, which represents it as a function that decreases non-linearly over time.

Unlike function A, function B would do a better job at capturing the increased uncertainty inherent in decisions made about events that are likely to occur farther into the future. That is, in general, we can have more certainty about events that will happen tomorrow than events that will happen in 1, 10, or 100 years. After all, who knows what society will be like in 100 years? Function B, therefore, suggests responsibility should reduce more rapidly than function A to capture the effects of exponentially increasing uncertainty.

These are just two options among many, and omit many questions and details:

- Once we have selected a function, how should we then operationalise the decrease in responsibility and, say, construct a measure to guide decision-making (e.g. an increasing reduction in the time spent deliberating about possible impacts for longer-term consequences)?

- How would such a function interact with the spatial dimension? Should groups of people that are separated from us both spatially and temporally receive less consideration (e.g. unborn people across the globe)?

- Do organisations with access to greater resources have a commitment to consider a wider and deeper range of impacts (e.g. social media companies or multi-national technological companies that create globally impactful systems)? To what extent does this commitment exceed the commitment of a small, national research team?

Next Steps¶

In this module, we have identified a series of challenges but have not considered how to address them. This is intentional. Our goal so far has been to understand the challenges at a conceptual level. We have not looked at how we can address the challenges in practical terms.

As such, you have encountered many questions without any answers. Fear not, as we move into the later sections, you will begin to encounter practical tools and procedures that can help you address similar challenges when they arise in your own projects.

-

This article from the PAIR team at Google provides a simple illustration of this phenomenon. ↩

-

Singer, P. (1997). The drowning child and the expanding circle. New Internationalist. https://newint.org/features/1997/04/05/peter-singer-drowning-child-new-internationalist ↩