Situated Explanations¶

At the start of this module we looked at a case of a generative AI producing images (or, digital art) that were difficult to explain.

At the start of this module we looked at a case of a generative AI producing images (or, digital art) that were difficult to explain.

Image creation is just one example of generative AI's capabilities. In addition to artwork, generative AI can also be used to create realistic images and videos of scenes or people (often referred to as 'deepfakes'). And beyond visual media, generative AI can also be used to generate text, code, and even music. Let's look at the first case, text. Most, if not all, forms of generative AI suffer the same explainability barrier as the image generation example. However, this does not mean that the requirements for explainability are the same. This is because the sociocultural context in which the systems are deployed create different expectations for valid and accessible explanations. Therefore, we need to consider the situation in which the system is deployed, and the users of the system, when we think about explainability. In other words, we need to understand what is required for the delivery and communication of situated explanations.

Ethics of Generative AI

There is a lot to say about the ethics of generative AI, outside of the context of explainability.

However, as this would be tangential to our current focus for this section, we will not say more about this beyond the need to maintain a critical perspective on its development and use.

The following resources are useful for further reading:

Note: a resource list is coming soon!

Building upon interpretability and transparency to develop situated explanations¶

At the time of writing, the most popular approach to AI generated text is the use of large language models (LLMs). In the words of one LLM, known as ChatGPT:

A large language model is a machine learning model that has been trained on a large dataset of text data, and can generate or predict text. It can understand and respond to human language, and can be used for a variety of natural language processing tasks, such as language translation, text summarization, and question answering. Examples include GPT-3, BERT, T5, etc.

Note: This text was generated by an AI system (built using a large language model) in response to the following prompt, 'What is a large language model?'. You can notice that there are dubious statements and possible inaccuracies, such as the claim about LLMs being able to "understand" human language. This is why it is always important to ensure that LLMs and other forms of generative AI are used responsibly, and that their limitations are well understood.

LLMs such as ChatGPT rely on a neural network approach for training the model. Specifically, they use an architecture known as a transformer.

Understanding a little about how transformers operate can help us tease out some important lessons for "situated explanations". Therefore, we're going to explore a short tangent before coming back to the main topic of this section.

Transformers and LLMs¶

Transformers are trained using unsupervised learning—a type of machine learning where the learning algorithm attempts to find patterns and structure in data without explicit supervision or labelled examples. In the case of LLMs, large datasets of text are used as training data and the LLM learns to predict the next word in a sentence (i.e. the prompt) based on the preceding words. The key innovation of the transformer architecture is the use of so-called "attention mechanisms".

These mechanisms are an important part of how LLMs can be made interpretable, although it is important to remember that LLMs are first and foremost an example of black box systems—a point we will return to shortly. The attention mechanism used by transformers allows the model to "attend" to specific parts of the input (e.g. the sequence of word, or 'tokens') when making predictions. Different weights are then applied to each position in the sequence based on its relevance to the current context. This process can be repeated millions (or sometimes billions) of times on a vast datasets of text until the model has learned to generate coherent and meaningful sentences.

What are tokens?

In natural language processing (NLP), an input sequence is typically divided into individual units of meaning called "tokens". Depending on the task, these tokens can be words, subwords, or individual characters. LLMs such as GPT-3 and BERT are two examples of NLP systems.

You will notice here, a similar process used by some of the other algorithmic approaches and models discussed in the previous sections: feature summary statistics and values for model internals are popular approaches to interpretability. However, the attention mechanism that neural-network based LLMs use is applied to multiple layers of the transformer's architecture. This allows the model to capture long-range dependencies and encode complex relationships between different parts of the input sequence, which in turn allows LLMs to produce more coherent and meaningful text. For instance, there is a substantive difference in the following two tasks, both of which involve a prompt:

- Complete the sentence: "Mark is looking for ... keys."

- Write me a press release for a new quarterly earnings report. The company is called 'Widgets Inc.' The profits are up 20% from last quarter.

In the first example, filling the gap with the word "his" is sufficient to complete the sentence and the important features would probably be 'Mark' and the target object, 'keys'. Such an approach would also allow members of a project team to easily identify gender bias in the model (e.g. associating specific genders with social roles, such as doctor or nurse).

However, in the second example, the task is much more complex, and the space of valid responses to the prompt is significantly more diverse. As such, simply showing the model's attention weights—calculated by comparing each token to all other tokens in the sequence and measuring the similarity between them—leads to a radically underdetermined explanation for why a particular answer was given.

While we have used LLMs as our illustrative example here, the same issues occur with many other types of black box AI systems, especially with neural networks. This raises an important question:

Question

If we can't fully understand or interpret the behaviour of a model or AI system, what supplementary information can we provide to ensure the behaviour and outcomes of the system are explainable?

Explainable Processes or Explainable Outcomes¶

By now, you may have noticed that there are two over-arching targets for explainability:

- The processes by which a model and it's encompassing system/interface are designed, developed, and deployed.

- The outcomes of the predictive model, which may be responsible for automated decisions or feed into human decision-making (e.g. decision support systems, visualisations).

This distinction between process-based explanations and outcome-based explanations was put forward in a guidance, titled 'Explaining decisions made with AI', which was developed by the Information Commissioner's Office (ICO) and the Alan Turing Institute. It is also how we will understand the differential needs for situated explanations.

The distinction helps to make clear some of the limitations referred to over the course of this module (e.g. limitations of post hoc methods of model interpretability). For example, a local, post hoc method will support explanations about why a model produced a specific prediction. This is in one sense, an outcome-based explanation, but it is also an incomplete outcome-based explanation.

To see why, consider a predictive model that classifies surveillance images as depicting illegal deforestation or not. The outcome may be a binary classification (i.e. yes/no), perhaps accompanied by a confidence score. But, the tangible real world consequences of this classification may be very different depending on the context in which the model is used. For instance, due to regulatory and compliance differences, two national bodies may choose to do very different things with this prediction. One may choose to notify local authorities to investigate, whereas the other may choose to do nothing.

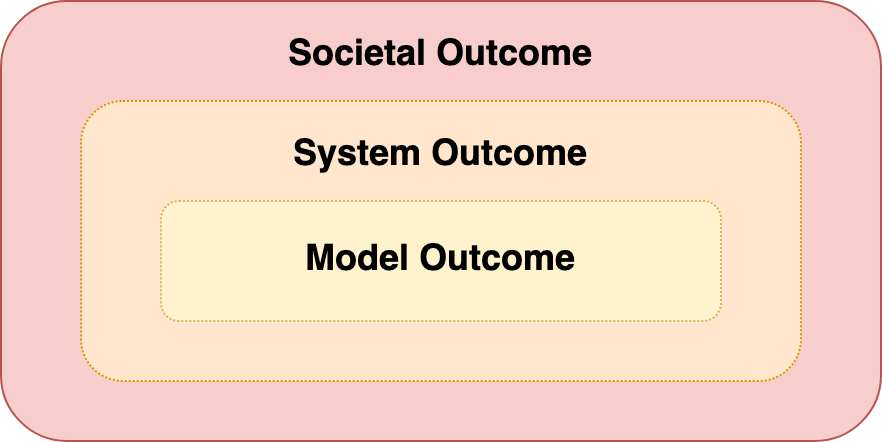

This simple (hypothetical) example shows that there is a further societal outcome that encompasses, but goes beyond, the outcome of the model itself. And, in between the model outcome and the societal outcome, there may also be a salient system outcome, depending on how the model has been implemented within the system that user's interact with (e.g. a recommendation system or a decision support system that serves as the interface between the model and the user).

Explaining the different outcomes (model, system, societal) will likely require varying levels of detail and granularity and may require those doing the explaining to refer to different processes across the project lifecycle.

For instance, asking the question "why did the model classify an image as an instance of illegal deforestation?" may require a more localised explanation about the model's internal processes and the data it was trained on. But asking the question, "why did the national body choose to do nothing on the basis of a prediction of illegal deforestation?" will require a more extensive and wide ranging explanation about how the system was designed, developed, and deployed, as well as an understanding of the societal and regulatory context in which the system is used.

Consider again the above example of two national bodies receiving predictions about illegal deforestation. Let's look at why the second body may have chosen to do nothing. Maybe they have a policy of not taking action on predictions with a confidence score below some threshold without additional assurance of how the confidence score was calculated. As such, they may have a need for an explanation about the following processes:

- Which experts were involved in the design of the system, and how did their involvement lead to the choice of decision threshold for the classifier?

- Which evaluation metrics were selected to assess the performance of the model, and why were these metrics chosen? How were biases such as training-serving skew assessed and mitigated?

- Were any steps taken during the model's implementation to accommodate variations in the quality of input data (e.g. low resolution images)?

All of these questions are requests for an explanation. Furthermore, they are all requests for an explanation about the processes that may or may not have contributed to the outcomes of the model.

Using the project lifecycle model to support explanations

The project lifecycle model introduced in the previous model provides a scaffold for thinking about which processes may be the target of an explanation. For example, each stage can serve as a deliberative prompt to help identify whether the typical tasks carried out during that stage could provide salient information to help address the request for an explanation.

Because the recipients of explanations have needs that may be different to those with technical expertise and deep familiarity with the model's architecture, it is not sufficient to simply provide an outcome-based explanation that relies on the outputs of post hoc methods of model interpretability. For instance, if the request for an explanation come from a machine learning engineer, the questions may have been very different.

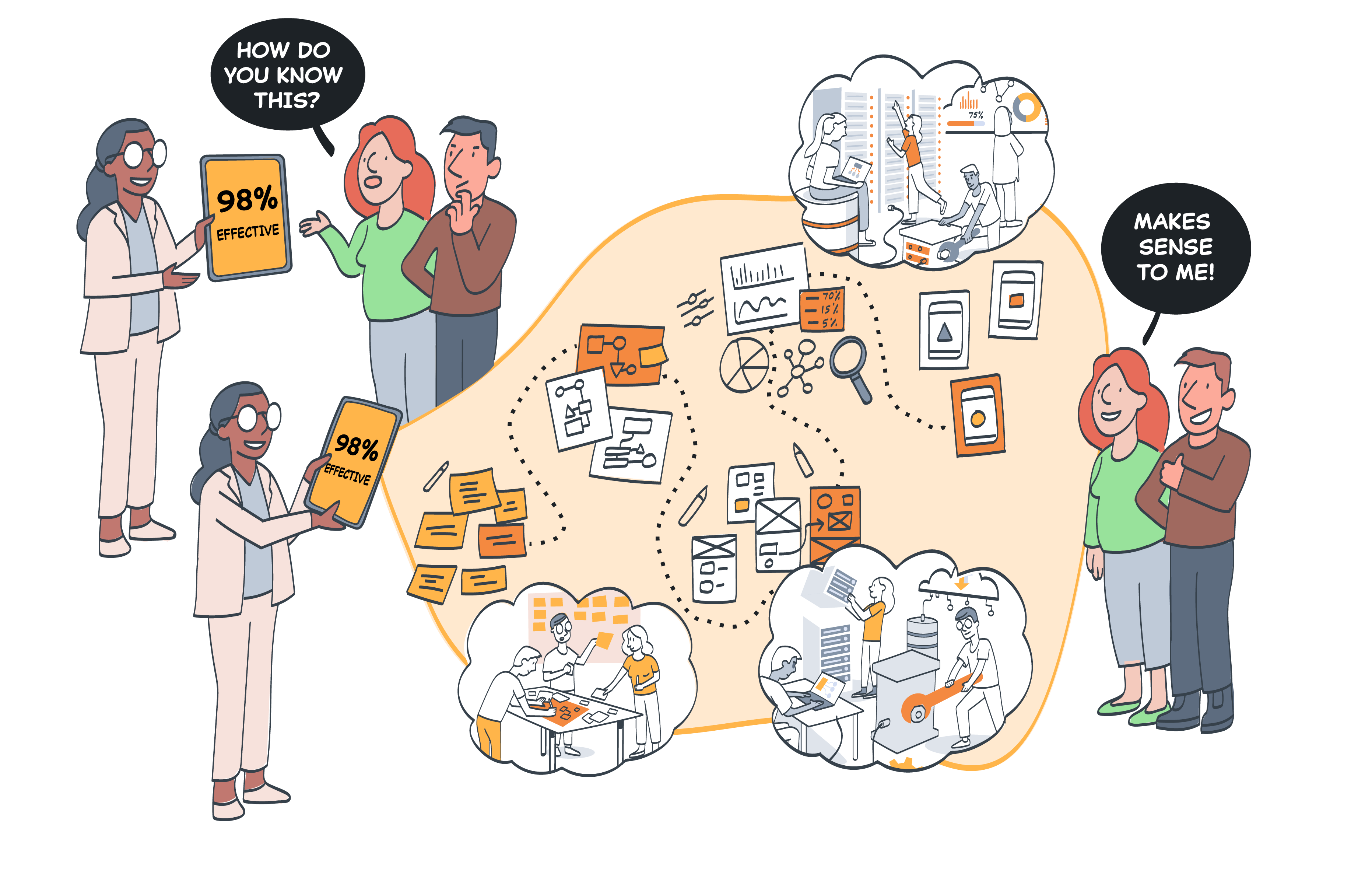

This is why we refer to 'situated explanations'. The term 'situated' is used to emphasise the importance of the context (or, situation) in which explanations are requested, and the stakeholder that is being engaged. Having an awareness and appreciation of these contextual factors is important for identifying what the 'explainability' requirements for a project will be, and can only be suitably addressed through informed and meaningful stakeholder engagement—ideally, early on in the project's lifecycle and in an ongoing and iterative manner.

Situated Cognition

There is a further sense in which explanations are situated, which draws upon research in the behavioural and cognitive sciences known as 'situated cognition'.

Situated cognition is a theory that emphasises the importance of our environments and social context in which learning, decision-making, and cognition more broadly take place. The theory suggests that our cognition is not a process that exists solely within our brains, but is instead shaped and influenced by the situation or context in which it occurs.

A simple example would be a chef who relies on her external environment to offload certain cognitive tasks to her environment (e.g. "remembering" the ingredients and order for a recipe by ensuring the ingredients are carefully laid out in front of her, and any tools or equipment are within easy reach).

Situating explanations is important in this sense, because it also recognises the importance of the context in which a recipient of an explanation will evaluate the explanation based on their own contextual or environmental influences.

If you're interested in reading more about situated cognition, the following resources are a good place to start:

- Hutchins, E. (1995) Cognition in the Wild. MIT Press.https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262581462/cognition-in-the-wild/

- Clark, A (1998) Being There: Putting brain, body and world together again. MIT Press.https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262531566/being-there/

- Robbins, P. and Aydede, M. (2009) A Short Primer on Situated Cognition. Preprint Available: https://philarchive.org/archive/ROBASP-4

Proportionality and the Demands of Explainability¶

In closing this section, let's look at one final question:

Question

How much resources should a project team invest in improving the explainability of their model or system?

As we have seen, improving the explainability of a system is not a trivial feat. It can require, among other things, access to technical and domain-specific expertise for ensuring model interpretability, resources for clear and accessible documentation to support project transparency, and opportunities for meaningful engagement with stakeholders to ensure a broad understanding of the sociocultural context in which the system will be used. The capacity of a team and organisation to meet these demands will obviously vary.

Therefore, a proportional approach to explainability will typically be required (as is also the case with the other SAFE-D principles). In short, this means weighing up what can be practically achieved within the constraints of the project (e.g. time, budget, and available expertise) against the normative demands of explainability. It does not mean identifying the bare minimum required and then stopping there, regardless of what the capacity of the team supports.

A general rule for helping assess what a proportional investment in explainability should be is the following maxim:

The greater the impact and scope of a system, the greater the need for explainability.

For instance, the use of a generative AI model that produces short jingles for elevators—admittedly, an absurd use case—is hardly creating any significant impact or risk of harm, beyond the potential for mild annoyance. However, at the other end of the spectrum, a black box AI system that classifies citizen's based on widespread data surveillance and is used to make decisions about their access to public services, could have a significant impact on the lives of millions or billions of people. The former barely creates any need for explainability, whereas the latter would require a significant investment in explainability to ensure its responsible design, development, and deployment.