What is the Project Lifecycle?¶

The proof is in the pudding, so let's start with the model itself.

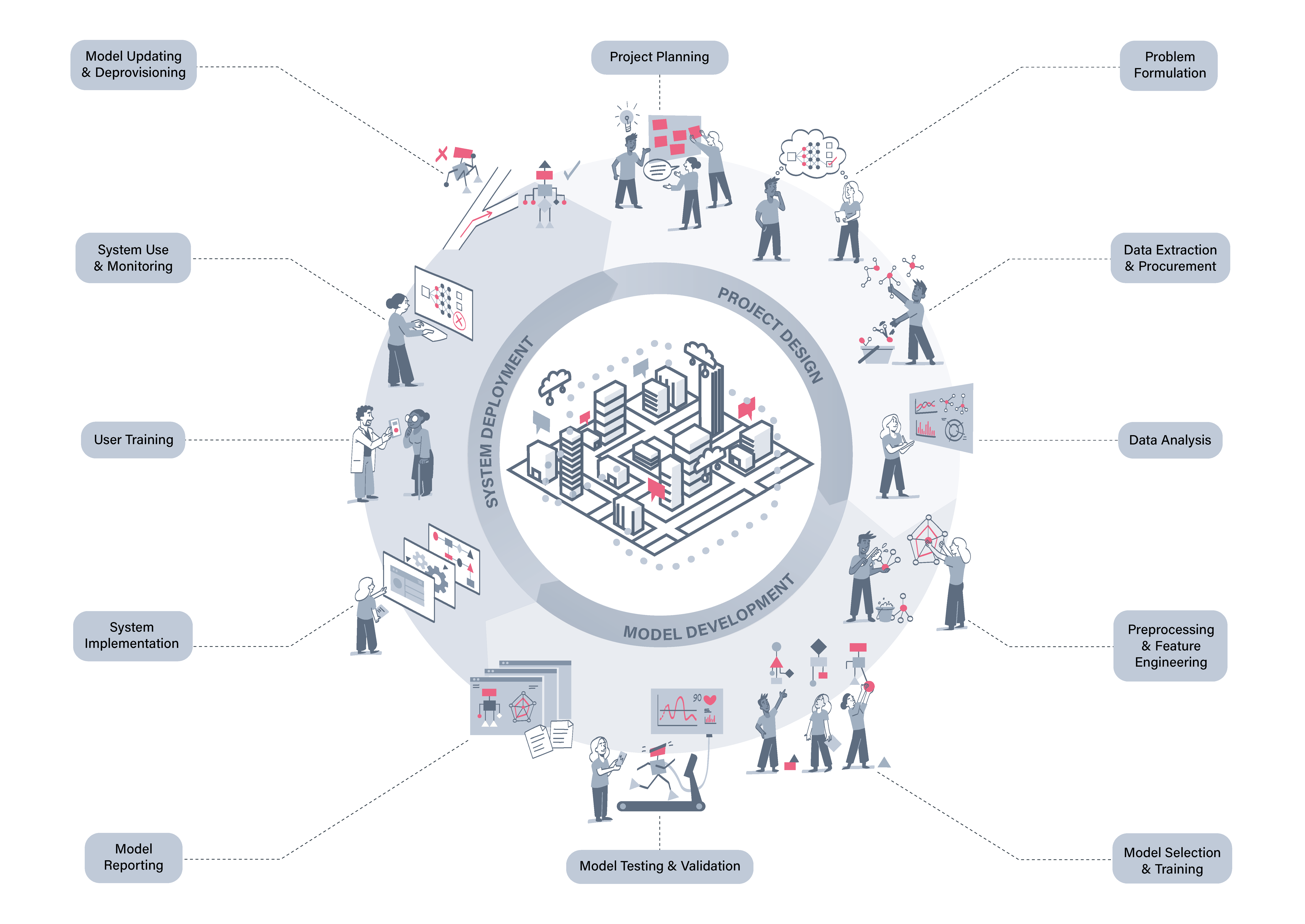

This model shows the typical stages of a project, which involves the design, development, and deployment of some data-driven technology, such as a ML algorithm or an AI system.

This module will explore each of the stages in detail. But let's start with some caveats about how the model has been designed, and how it functions.

A Heuristic Model¶

The Project Lifecycle is a heuristic model that serves as a "cognitive scaffold" to support the collective reflection, deliberation, and decision-making of teams and organisations throughout the various stages of a project's lifecycle. Why do we call it a "heuristic model"?

All models are wrong, but some are useful. -- George Box

This famous statement from the British statistician, George Box, highlights a universal truth about models: they all make various assumptions that affect their representational validity. Our model is no different. It makes assumptions about how a typical project, involving some data-driven technology, is structured (e.g. which stages follow from their predecessors). The reality will differ within and between project teams and organisations. Different projects carried out by the same team could differ, and small organisations are likely to govern projects very different to distributed, multi-national projects.

Question

The question then is whether and how the project lifecycle model is useful?

Scaffolding Reflection, Deliberation, and Decision-Making¶

The model can be useful for several processes or outcomes, including:

- initial reflection about the tasks or actions that should be undertaken at the respective stages,

- deliberation about how the tasks and actions may undermine or promote relevant project goals and objectives (e.g. developing a fair classifier), and

- ongoing decision-making as the project unfolds and actions are documented.

We will demonstrate and justify these claims over the course of this module.

The Over-Arching Stages¶

There are two layers to the model:

- The three over-arching stages

- The twelve lower-level tasks

Let's start with the over-arching stages.

Three over-arching stages in the Project Lifecycle model

The preliminary tasks and activities that set the foundations for the development of the model and system (e.g. impact assessments, data extraction and analysis).

The technical and computational tasks associated with machine learning, such as training, testing, validation, and documentation, which are necessary to ensure the model is appropriate for its intended use with the target system.

The tasks that ensure the safe and effective deployment and use of the system (and underlying model) within the target environment by the intended users. This stage includes ongoing monitoring, as well as tasks associated with updating or deprovisioning.

Properties of the Model¶

In addition to its general structure, there are also some noteworthy properties of the model:

- The model has a high-degree of representational accuracy for typical

researchanddevelopmentprojects that involve some form of data science or artificial intelligence (e.g. machine learning algorithms). That is, while it is "wrong" in the manner expressed above by George Box, it is less wrong for projects involving data-driven technologies. - Although the model is presented as a uni-directional process for simplicity, it is expected that actual research and development practices will involve iteration between stages as well as multiple and simultaneous streams of work (e.g. Agile projects).

- The model is circular to acknowledge that the deprovisioning of a system may require a new project to commence (e.g. to meet ongoing business needs, or to prevent lock-in due to technical debt). This is an important part of responsible research and innovation—taking responsibility for future outcomes, and not just "washing your hands" when a model or system is deployed.

Who is the model for?¶

The model is primarily for anyone who is directly involved with the project in question, and who has some role within or responsibility over one or more of the stages. For example, the model is as much for the data analyst or systems engineer, as it is for the project manager who has oversight over the project itself.

The reason for this is two-fold:

-

The model is intended to create a common conceptual vocabulary when communicating with those who are indirectly involved in the project (e.g. organisations engaged for procurement of data or services, wider stakeholders and affected users with whom the project team need to communicate). Recall the principle of 'engage' from the AREA framework in the previous module—having a shared or common vocabulary is important in engagement and communication.

-

Although some team members may have oversight over the project as a whole, this often establishes a more narrow form of accountability or liability, not responsibility. Having a model that can also show how roles and responsibilities become entangled in attempts to remain morally responsible is, therefore, also necessary.

Illustrative roles

Some illustrative roles include the following:

- Researchers (e.g. user researchers, data scientists, social data scientists)

- Developers (e.g. ML architect, software and systems engineers)

- Project governance (e.g. quality assurance, system auditing, data custodian, data protection impact officer, project manager, product owner)

Entangled Ethical Decisions

We will explore concrete examples of how ethical decision-making is entangled (or embedded) in the various roles and responsibilities of a project team over the course of this module. For now, if this second reason is unclear, try to recall the discussion in the first module about collective responsibility.

Why and how should you use the model?¶

There are many ways in which this model can be used and we will explore some uses in detail over the course of this module.

Pragmatic uses of the lifecycle model

For now, the following illustrative examples may help understand the pragmatic aspects of the model:

- Prior to the start of a project, the model can be used as a

checklistreflect-list of tasks and activities that are likely to have ethical significance (e.g. bias mitigation assessment during project planning). - The scaffolding (or structure) provided by the model can support the continuous deliberation and documentation of actions and decisions taken as a project evolves (i.e. development of a living document). For example, as tasks are handed over to others, documentation about previous and upcoming decisions or actions can be built upon.1

- Towards and at the end of a project, the repository of documented evidence can then serve as an accessible and transparent record of the project's activities and governance.

-

Here, additional use of version control technologies (e.g. Git and GitHub) could also enable an open and transparent form of project governance and documentation, when stored alongside data or code in a public (or shared) repository. For instance, keeping track of ethical decision-making recorded against the activities of the project as it unfolds. ↩