Identifying and Mitigating Bias¶

In the previous two sections, we explored theoretical and conceptual topics related to sociocultural and statistical fairness. In this section, we will bring this knowledge and understanding together to consider how we can identify and mitigate bias in machine learning and AI systems.

Mitigating Bias

The use of the term 'mitigating' bias is used in place of 'removing' or 'eliminating', as it is important to acknowledge that bias can never be completely removed or eliminated.

Identifying Biases¶

Biases can affect the design, development, and deployment of machine learning and AI systems at many stages and in many ways. This is why the project lifecycle model has been designed to scaffold collective reflection, deliberation, and practical decision-making. The use of the project lifecycle model allows individuals and teams to systematically identify where biases may be present before the start of a project, or how specific biases can impact particular stages and cascade downstream.

For example, perhaps you have heard about biased algorithms used in hiring or recruitment, which can discriminate against certain groups of people and make it comparatively harder for them to get a job.1 Or, perhaps you have heard about biased machine learning systems that learn discriminatory patterns from the healthcare data they are trained on, resulting in unfair decisions being made about certain groups of patients.2

Identifying the source of these biases, their impact on the design, development and deployment of the respective system, and the societal effects on individuals and communities is a complex task. In the case of a biased hiring algorithm, for example, an important source of the biased decision-making was the data used to train the algorithm, but this data itself was an encoding of biased hiring practices within society and the organisation that predate the algorithm. Moreover, the deployment and ongoing use of the algorithmic system would further exacerbate bias in hiring, leading to a self-reinforcing cycle of discrimination.

While the project lifecycle model is one supporting structure for identifying and mitigating bias, it is not the only one we will need. We also need to have a conceptual understanding of the different types of bias that can impact machine learning and AI systems, and how these biases can be mitigated. Therefore, in this section, we will introduce a simple taxonomy of biases and discuss how we may identify and mitigate them.

Types of Bias: Social, Statistical, and Cognitive¶

You will likely have some prior familiarity of the term 'bias', but your understanding of the concept may be grounded in a particular context, such as a disciplinary background (e.g. a formal understanding of bias as statistical bias) or a lived experience (e.g. political or social discrimination).

This section will look at three types of 'bias' as they apply to and affect the project lifecycle model. The three perspectives that we will look at are: social, statistical, and cognitive bias.

Social Bias¶

Social bias is the most wide-ranging of our three terms. In general, we can define social bias as follows:

The presence of systematic and unfair assumptions, prejudices, or stereotypes that exist within society and that become encoded within the data used to design and develop algorithmic systems.

As such, 'social bias' is the most morally loaded type of bias in our taxonomy, as it is often associated with some form of prejudice or discrimination that is morally abhorrent or wrong. For example, an inclination or disposition to treat an individual or organisation in a way that is considered to be unfair based on the presence of some characteristic or attribute (e.g. age, race, gender, political orientation). This understanding of bias is necessary to draw attention to pre-existing or historical patterns of discrimination and social injustice that can be perpetuated, reinforced, or exacerbated through the development and deployment of data-driven technologies. However, it is also one of the hardest to identify from within the project lifecycle, as many of the sources of social bias predate the design or development of the system in question.

This is, perhaps, why many focus on 'data bias' as a more tractable and manageable problem, as identifying biased data is one step along the path to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the social biases that underpin it.

However, it is also important to recognise that while some social biases can be identified through exploration and analysis of the data, the way to mitigate the underlying bias is not always to simply improve or augment the data themselves.

Selection Bias: An Example

To illustrate the above point, consider the following example of selection bias.

Selection bias is a term used for a range of biases that affect the selection or inclusion of data points within a dataset. For instance, where individuals differ in their geographic or socioeconomic access to a study that is being performed to collect data, the fact that some participants may struggle to travel could be a reason for their systematic exclusion from the study. Or, in the case of the digital divide issue raised in the first section, if data collection is only carried out online, then members of society without access to a smartphone or the internet may not be appropriately represented in the data.

While it may be possible to spot this missingness during data analysis, the appropriate solution to this social bias (e.g. improving access or reducing the digital divide) is clearly not just a matter of improving the data itself. Even if the dataset could be augmented to include the missing data, it would not address the underlying social bias that is causing the data to be missing in the first place.

Statistical Bias¶

If you are a data scientist, or use techniques from data science in your research or development, then it is likely that your understanding of bias is influenced by statistical concepts.

Jeff Aronson explores the etymology of the term 'bias' in a series of interesting blog articles, which emphasise the statistical understanding of bias.3 He begins by tracing it back to the game of bowls, where the curved trajectory of the bowl as it ran along the green reflected the asymmetric shape of the bowl (i.e., its bias). However, according to Aronson, the term was not used in statistics until around the start of the 20th century where it was used to refer to a systematic deviation from an expected statistical result that arises due to the influence of some additional factor. This understanding is common in observational studies where bias can arise in the process of sampling or measurement.

On the basis of his historical review, Aronson identifies six features of definitions of bias that help to characterise an understanding of statistical bias:

- Systematicity: bias arises from a systematic process, rather than a random or chance process.

- Truth: a realist assumption that the deviation is from a true state of the world.

- Error: the bias reflects an error, perhaps due to sampling or measurement.

- Deviation (or Distortion): a quantity in which the observed result is taken to differ from the actual result were there no bias.

- Affected elements: the study elements that may be affected by the bias include the conception, design, and conduct of the study, as well as the collection, analysis, interpretation, and representation of the data.

- Direction: the deviation is directional, as it can be caused by both an under- or over-estimation.

While some of these features are specific to a statistical framing of 'bias', others can be used to enhance our understanding of the other types of bias. For instance, 'systematicity' is arguably a necessary property for social biases (i.e., a bias that systematically leads to discriminatory outcomes). And, 'error' is sometimes a property of our next category: cognitive biases.

Following Aronson's lead, we can define statistical bias as follows:

"A systematic distortion, due to a design problem, an interfering factor, or a judgement, that can affect the conception, design, or conduct of a study, or the collection, analysis, interpretation, presentation, or discussion of outcome data, causing erroneous overestimation or underestimation of the probable size of an effect or association".

Training-Serving Skew: An Example

Training-serving skew is a bias that occurs when there is a mismatch between the data used to train a machine learning model and the data encountered during deployment. More specifically, training-serving skew arises when the distribution of the data used to train the model is different from the distribution of the data that the model encounters during deployment and use within its production (or runtime) environment.

Consider a model that predicts credit risk for loan applicants. The model is trained on a dataset that includes information about the loan applicants, such as their income, employment history, and credit score. But, there is a disproportionate number from one demographic group in particular (e.g. elderly applicants). As we train the model on this dataset, it may learn to associate certain characteristics with lower credit risk, which are not representative of the underlying relationship in the broader population.

When the model is deployed in production, therefore, and used to make predictions for loan applicants from other demographic groups (e.g. younger applicants), the model's performance will be biased in favour of the older applicants.

Cognitive Bias¶

There are many cognitive biases, and others have put forward taxonomies that focus specifically on cognitive biases. This level of detail is not needed for our present purpose, so let's just define cognitive bias as follows:

A tendency or predisposition for a person to form a judgement, recall information, or make a decision on the basis of a (potentially adaptive) heuristic, which in certain contexts can lead to the deviation from a proposed norm of rationality (e.g. logical reasoning).

Our modern understanding of cognitive biases has been most heavily influenced by research conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky4. A lot of their work exposed a wide variety of psychological vulnerabilities, which impact our judgement and decision-making capabilities. In short, their experiments showed how individuals rely on an assortment of heuristics or biases, which speed up judgement and decision-making but also lead us astray.

For example, consider the following example.

The Linda Problem

Linda is 31 years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.

Which is more probable?

1) Linda is a bank teller. 2) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement.

Try to answer this question yourself, before you reveal the answer.

Reveal

The correct answer is (1). Did you get it right?

If you got it wrong, you have just committed what is known as the 'conjunction fallacy'. But don't worry you're in very good company! When Tvserky and Kahneman posed this question to a group of 88 undergraduate students, only \(15%\) got the correct answer.5

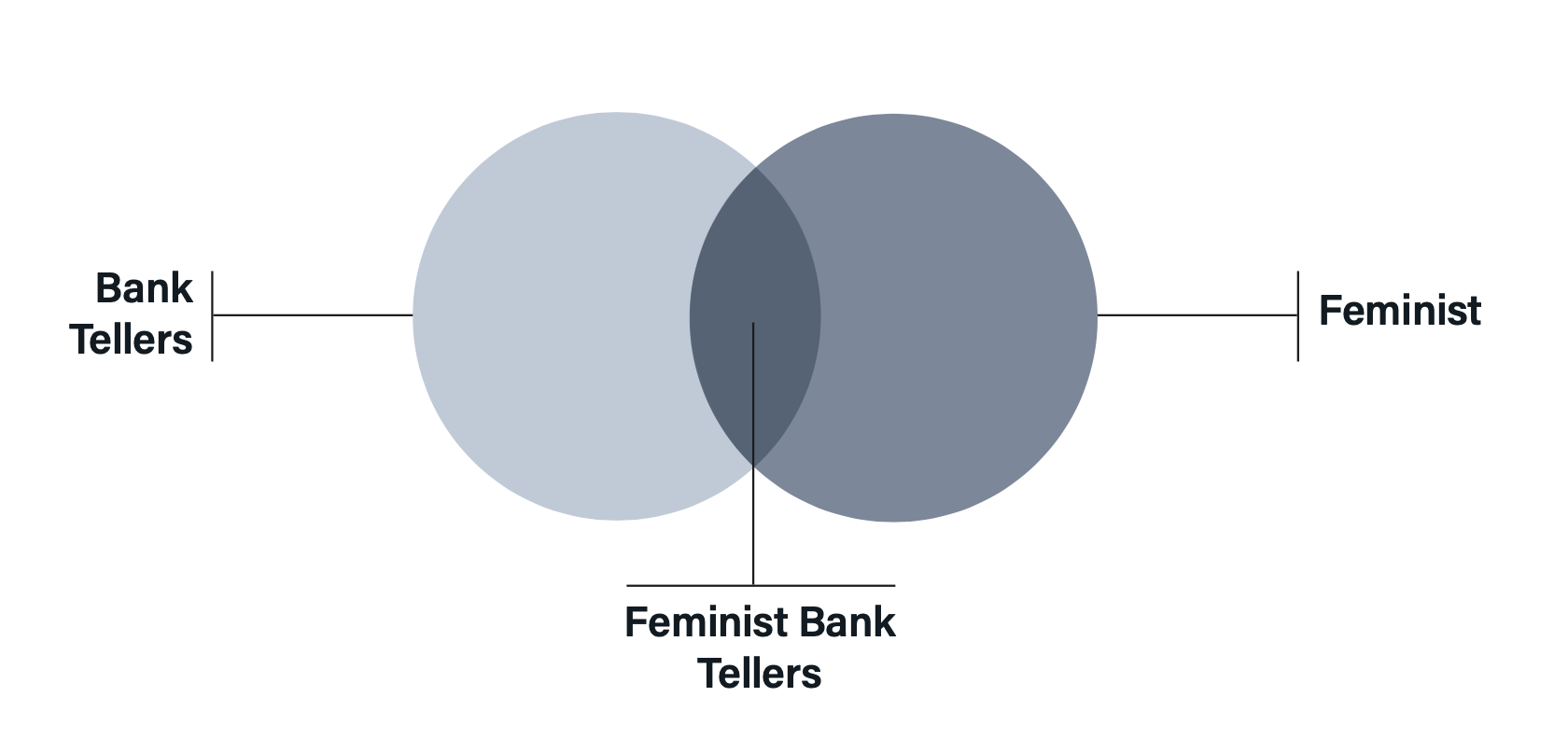

The reason it is (1) is because the probability of two events occurring in conjunction, such as Linda being both a 'bank teller' and 'active in the feminist movement' must be less than or equal to the probability of either event occurring on its own. Formally, for two events \(A\) and \(B\):

\(Pr(A \wedge B) ≤ Pr(A)\) and \(Pr(A \wedge B) ≤ Pr(B)\)

Or, to put it more simply, someone cannot belong to the set of feminist bank tellers without also belonging to the set of bank tellers 👇

Tversky and Kahneman attributed this systematic error to what is known as the representativeness heuristic. In short, people don't think about the conjunction of events or consider probability theory when formulating an answer. Instead, their choice is based on which of the two options is most representative of the description of Linda. That is, they employ a mental shortcut (or, a heuristic) that in some instances lead to the right answer—hence, their efficiency. However, in in other cases their use lead to mistakes or errors in judgement.

A critical perspective on the view of judgement and decision-making put forward by Kahneman and Tversky would view it as an attempt to catalogue a variety of cognitive failures or irrationalities that stem from an individual’s inability to perform rational calculations. In this sense, cognitive bias would overlap with the 'error' component of statistical bias identified above.

However, those who adopt a view known as 'ecological rationality' argue that such a perspective judges human agents against a normative standard of rationality that is unsuitable for situated agents whose choice behaviour is constrained by myriad cognitive and environmental factors (e.g. temporal constraints that force decisions, limited information). This alternative account, made famous by Herbert Simon, and later developed by Gerd Gigerenzer reframes a lot of human judgement and decision-making as underpinned by “fast and frugal” heuristics, which are highly adaptive and support decision-making in complex and uncertain environments. It's not necessary to delve into this debate for the present purposes, but it is an interesting tangent for those interested in exploring how the choice to present statistical information in different ways (e.g., as probabilities versus frequencies) can affect comprehension and understanding.6

When carrying out research and innovation in data science and AI, cognitive biases can have a variety of impacts on the tasks of the project lifecycle.

Confirmation Bias: An Example

Confirmation biases arise from tendencies to search for, gather, or use information that confirms pre-existing ideas and beliefs, and to dismiss or downplay the significance of information that disconfirms one’s favoured hypothesis. This can be the result of motivated reasoning or sub-conscious attitudes, which in turn may lead to prejudicial judgements that are not based on reasoned evidence.

During the data analysis stage of the project lifecycle, for instance, confirmation bias could lead a data scientist to interpret the data in a way that supports her prior beliefs or assumptions, rather than considering alternative explanations.

Perhaps the data scientist is exploring a dataset on the effectiveness of a new drug, and has a hypothesis that the drug is highly effective.

Confirmation bias would cause her to selectively focus on information that supports her hypothesis, while overlooking information that contradicts it.

Mitigating Bias¶

Now that we have a better understanding of the different types of bias, we can consider how to mitigate them. Although the specific mitigation strategies will vary depending on the particular bias, the bias taxonomy allows us to consider some general strategies and constraints.

| Type of Bias | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|

| Social Bias | Carry out inclusive, diverse, and meaningful stakeholder engagement with specific attention paid to identifying communities or groups that have additional barriers to participation. Analyse gaps in demographic data in consultation with community groups and domain experts. Develop appropriate methods to address gaps and limitations based on context-aware reflection. Organise participatory design workshops during project planning and problem formulation to ensure that the project is addressing the right problem and that the solution is appropriate for the intended users. |

| Statistical Bias | Ensure that the data collection and analysis processes are transparent and well-document, and that, where possible, data and methods are publicly available to allow for reproducibility or replicability of results. Use additional evaluation metrics for your model to determine whether its performance applies equally for all individuals or sub-groups. Where relevant carry out intersectional analysis of multiple demographic or identity characteristics to identify biases that may not be apparent when considering a single characteristic. Augment your dataset using techniques appropriate to the objective (e.g. addressing sparsity), such as data linkage or mixing, synthetic data generation, imputation, adding noise, transformation. |

| Cognitive Bias | Request a targeted and critical review of work by a committee, red team, or other group, who are tasked with finding gaps or issues. It is much easier to spot cognitive biases in the work or reasoning of others than ourselves. Carry out early and ongoing forms of user engagement and training to ensure that best practices are adopted in the use of and interaction with the system (e.g. minimising automation bias). Organise and facilitate skills and training events, such as webinars, workshops, self-directed learning, to upskill project team members or users (e.g. understanding and communicating uncertainty of predictive models, interactions with system interface). |

You will note from the selection above that the mitigation strategies are likely to require diverse forms of expertise and knowledge. For instance, the use of 'evaluation metrics' to mitigate statistical biases will require a good understanding of the statistical properties of the data and the model. As such, this type of work can only be carried out by members of the team with high levels of statistical literacy or technical expertise (e.g. data scientists, data engineers, data analysts, etc.). In contrast, many of the mitigation strategies for social biases will require a good understanding of the social context in which the project is being carried out, which will require the involvement of individuals with specific domain expertise or experience in facilitation (e.g. social scientists, community organisers, etc.).

However, a responsible approach to project governance and management will ensure that the team has the necessary expertise and capacity to carry out the work required to mitigate the identified biases. Admittedly, this can be a challenge for many projects, either because they may be carried out by teams that are highly specialised in a particular technical domain (e.g. computer vision, natural language processing, etc.) or because the team are under-resourced and do not have the capacity to bring in additional expertise. However, as is the case with many of the SAFE-D principles, the proposals outlined above can be treated as a set of practical guidelines to strive for, rather than as a set of non-negotiable criteria that serve as a checklist to be ticked off.

Bias Checklist Reflectlist Activity

The activity that is associated with this module takes the concepts introduced in this section further, and allows you to carry out a structured process of identifying possible biases and recording where in the project lifecycle they may arise, and what sorts of mitigation strategies might be appropriate to address them.

The activity can be carried out in a group or on your own, and we encourage you to give it a try. You can download a copy of the activity handout here.

-

Dastin, J. (2018, October 11). Amazon scraps secret AI recruiting tool that showed bias against women. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight-idUSKCN1MK08G ↩

-

Obermeyer, Z., Powers, B., Vogeli, C., & Mullainathan, S. (2019). Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science, 336(6464), 447 - 453. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aax2342 ↩

-

Aronson, J. (2018). A word about evidence: 4. Bias \textemdash Etymology and usage. Catalogue of Bias. https://catalogofbias.org/2018/04/10/a-word-about-evidence-4-bias-etymology-and-usag/ ↩

-

For an excellent overview and introduction to this area, see Daniel Kahneman's book, Thinking, Fast and Slow. ↩

-

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1983). Extensional versus intuitive reasoning: The conjunction fallacy in probability judgment. Psychological Review, 90(4), 293 - 315. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.90.4.293 ↩

-

For those who want to reconstruct the debate between Kahneman, Tversky, and Gigerenzer, the following papers can be read in order: (1) Tsversky, A. & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgement under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science, 185(4157), 1124 - 1131. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.185.4157.1124, (2) Gigerenzer, G. (1991). How to make cognitive illusions disappear: Beyond "heuristics and biases". European Review of Social Psychology, 2(1), 83 - 115. https://doi.org/10.1080/14792779143000033, (3) Kahneman, D. & Tversky, A. (1996). On the reality of cognitive illusions. Psychological Review, 103(3), 582 - 591. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.3.582, (4) Gigerenzer, G. (1996). On narrow norms and vague heuristics: A reply to Kahneman and Tversky. Psychological Review, 103(3), 592 - 596. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.103.3.592 ↩